The third step of the Assessment Cycle is deciding how to measure your stated student learning outcomes (SLOs). During this step of the process, you will need to consider questions such as:

- Should you select a preexisting measure or develop a new one?

- What are the pros and cons of selecting or developing a new measure?

- Where can you find preexisting measures?

- Does the measure align with your SLOs?

- Which assessment items map to which SLOs?

- Are you using a direct measure of student learning?

- Is there reliability evidence associated with the measure’s scores?

- Is there validity evidence to support your desired interpretation of the scores?

Alignment of Instrument to SLOs

Verb-Instrument Agreement

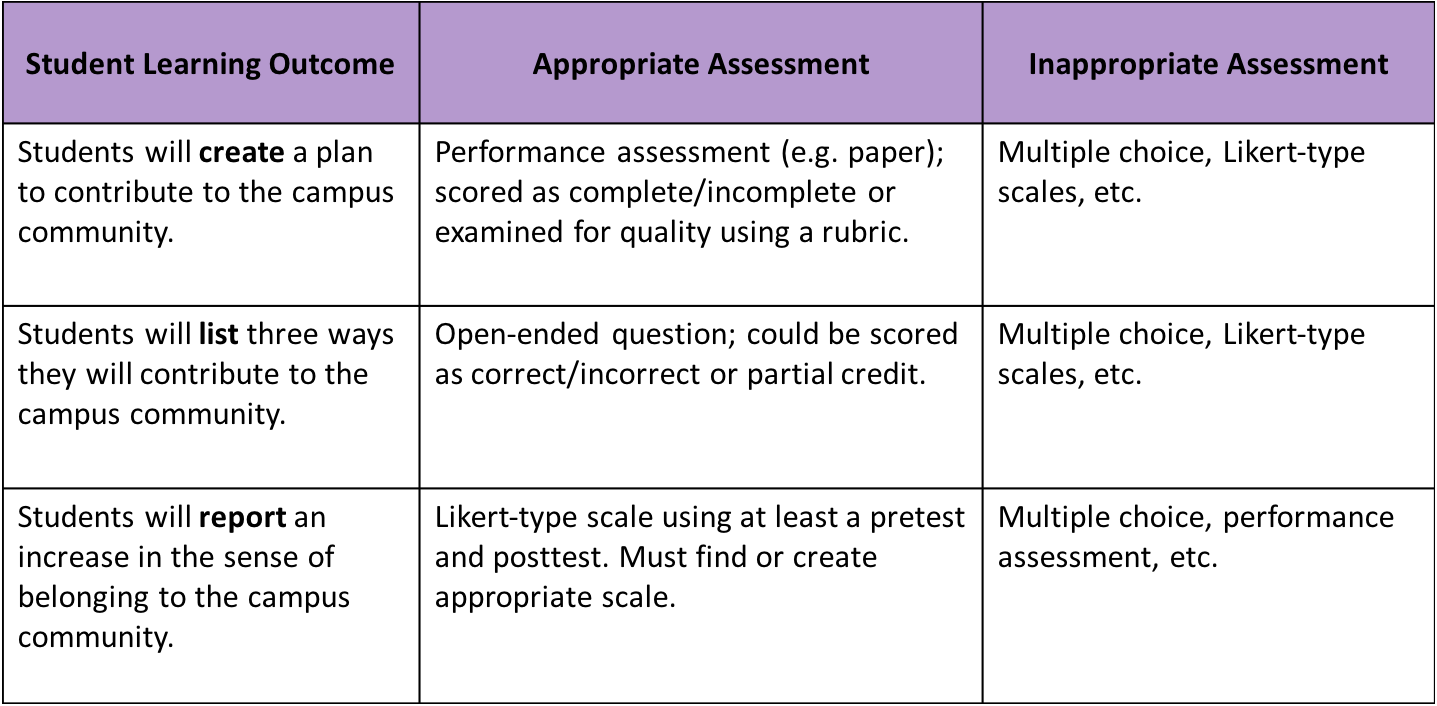

All SLOs include an action verb indicating what a student is expected to know, think, or do as a result of program participation. Each verb acts as a hint about what type of instrument is appropriate. For example, an SLO that states students will be able to "recognize" certain information could be assessed by a multiple choice or matching question. In contrast, for an SLO that states students should be able to "explain" something, an open-ended question would be more appropriate. Consider the additional examples below:

Instrument-to-Outcome Map

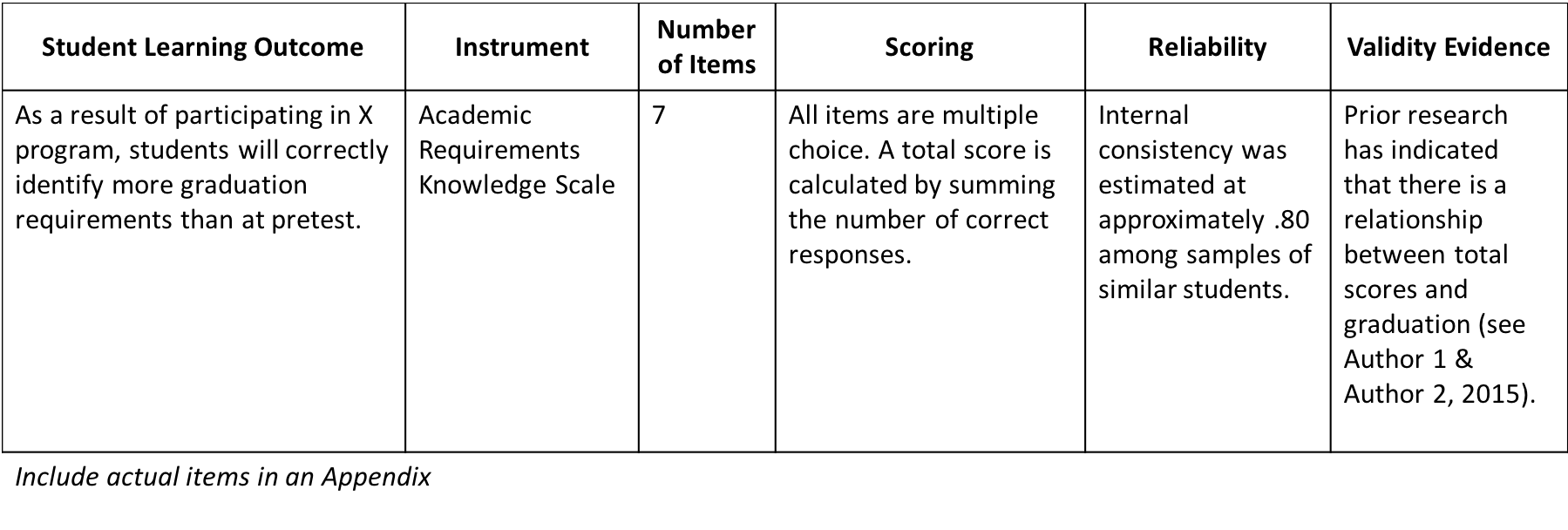

After selecting or designing an instrument that aligns with your SLOs, it is useful to develop an instrument-to-outcome map. In this map, you will specify which assessment instruments measure which SLOs. If an instrument measures more than one SLO, it may be helpful to identify which specific items map to each SLO. Additionally, it may be helpful to include information about instrument quality and how each instrument/item will be scored in your instrument-to-outcome map. Consider the example below:

Types of Instruments

There are three main types of instruments: cognitive instruments, attitudinal instruments, and performance assessments. As alluded to above, the verbs in your SLOs will dictate which type of instrument you should use.

Cognitive Instruments are generally used to assess knowledge or reasoning. Multiple choice tests are a classic example of a cognitive instrument. Other examples include matching items, true/false statements, short essays, and sentence completion items.

Attitudinal Instruments are concerned with the attitudes, beliefs, or preferences students may have. These instruments often use Likert-type scales that ask students to indicate the extent to which they agree or disagree with a certain statement.

Performance Assessments are used to evaluate students' skills and behaviors as evidenced through certain products or performances. More specifically, raters are trained to evaluate the product or performance according to a rubric that specifies various criteria for success.

Observational Protocols are used to assess behavioral outcomes that cannot be assessed via performance assessments. Some common examples include surveys, checklists, or structured guidelines completed by an observer. More information about designing and using observational protocols can be found on our observational protocols page.

Direct vs. Indirect Measures

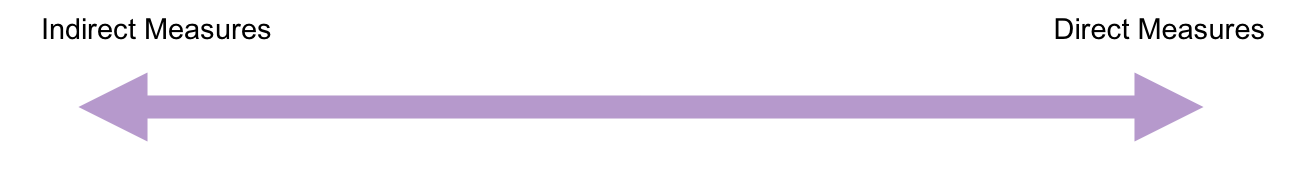

Often a distinction is made between "direct" and "indirect" measures. We generally consider direct measures of student learning to be instruments that require students to actually use the skills we are interested in measuring (e.g. a writing assignment meant to assess writing skills). In contrast, indirect measures do not call on students to use the skills being measured. Instead, these instruments rely on indirect evidence to infer that students possess certain skills (e.g., a self-report survey where students are asked to indicate whether they believe they've mastered various writing skills).

Although we often talk about instruments as being either direct or indirect, there is no such thing as a 100% direct measure. An instrument's "directness" is better conceived along a continuum ranging from relatively more direct to relatively less direct. Measures that are more direct are always preferable to those that are less direct.

It is important to note that the directness of an instrument depends on what is being measured. For example, if we were interested in students' critical thinking skills, asking them to indicate how good they think they are at critical thinking (a self-report measure) would be a less direct measure than an assignment asking them to critique a journal article. However, if we were interested in students' beliefs about their critical thinking skills, then the self-report measure would be considered more direct than the journal critique.

Selecting vs. Designing Instruments

Student affairs practitioners have two options when it comes to measuring their SLOs: selecting a preexisting instrument or designing one from the ground up. There are pros and cons to each approach. Generally speaking, however, it is best to select a preexisting instrument whenever possible.

Designing a good instrument (one that fully captures the knowledge and skills we care about without also capturing irrelevant factors) requires an extensive amount of time, resources, and expertise. We strongly suggest consulting with individuals trained in measurement theory before embarking down this path. Student affairs staff at JMU can schedule an appointment with SASS for assistance. See the table below for more information about selecting vs. designing an instrument:

Selecting

Advantages

- Convenience

- Reliability and validity evidence often available

- Able to make comparisons to others using the same instrument

Disadvantages

- Alignment (between instrument and SLOs) often less precise

- May be difficult to find a good instrument (many published instruments have poor psychometric properties)

- Cost (if purchasing a commercial instrument)

When to select

- When you want an instrument with strong psychometric properties (i.e., evidence of reliability and validity)

- When data need to be collected soon

- When your program is impacting attitudes or skills that have been well-studied (e.g., sense of belonging, cultural competency, career readiness, etc.)

Designing

Advantages

- The instrument is specifically tailored for your SLOs (i.e., strong alignment)

Disadvantages

- Resource intensive (it can take a year or more to develop a good instrument)

- Need to collect validity evidence (this process can also take several months)

- Comparisons to other groups may be limited

When to design

- When you can't find an instrument that aligns with your SLOs

- When your SLOs are highly specific (e.g., knowledge of JMU campus resources)

- When preexisting instruments have poor psychometric qualities

- When you have support from someone trained in instrument development

Where to Find Instruments

The video below provides resources and guidance on finding and selecting existing measures.

The databases below can be used to find both commercial and non-commercial measures. For more information about how to find instruments and for links to other databases, click here.

American Psychological Association Test Database - an unparalleled resource for psychological measures, scales, and instrumentation tools with over 50,000 records

Educational Testing Service (ETS) Test Collection - over 25,000 tests available for researchers, educators and graduate students

ERIC - an extensive online research database; use the advanced search feature to filter by publication type (i.e., tests/questionnaires)

Mental Measurement Yearbook - database that hosts tests from specific areas (developmental, personality). Also includes reviews and critiques for each test

How to Develop an Instrument

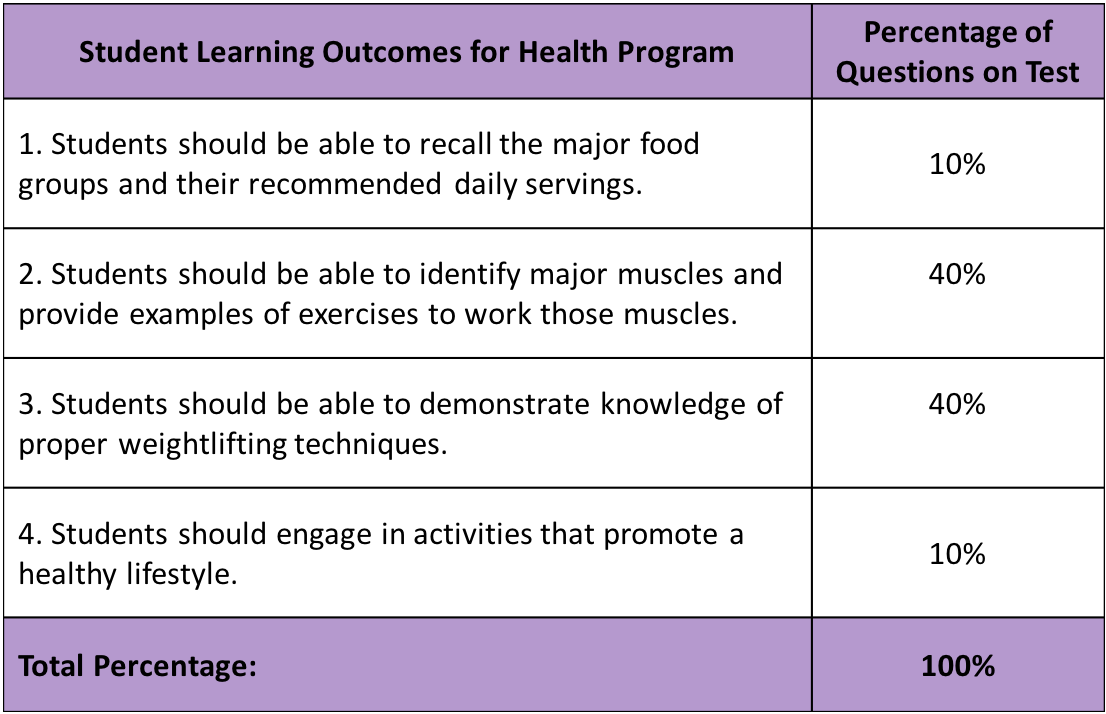

Table of Specifications

One of the first steps to developing an instrument is to create a test blueprint or table of specifications. This table indicates the number or proportion of items on the test that will be written to measure each SLO, skill, or skill dimension. For example, if we are interested in measuring "intercultural competency," we might decide that half of the items should be written to measure students' awareness of their own culture (self-awareness dimension) while the other half should measure students' knowledge of others' cultures (cultural awareness dimension). The development of the table of specifications should be guided by theory and your SLOs. You should ask, what do researchers say are the important dimensions of the skill I'm trying to measure? And, based on my SLOs what types of items should my test include? See the simplified example below:

General Guidelines for Item Writing

The following guidelines apply to the writing of cognitive or attitudinal items. For more information and a list of common item-writing mistakes, check out this presentation or this comprehensive guide to item writing.

Cognitive Items

-

- Offer 3-4 well-developed answer choices for multiple-choice items. The aim is to provide variability in responses and to include plausible distractors.

- Distractors should not be easily identified as wrong choices.

- Use boldface to emphasize negative wording.

- Make answer choices brief, not repetitive.

- Avoid the use of all of the above, none of the above, or a combination such as A and B options. It is tempting to use them because they are easy to write, but they tend to lower reliability and make it harder to distinguish between high and low ability students.

- For matching items, provide more response options than items in the list (e.g., offer 10 response options for a list of seven items). This decreases the likelihood of participants getting an answer correct through the process of elimination.

- List response options in a set order. Words can be listed in alphabetical order; dates and numbers can be arranged in either ascending or descending order. This makes it easier for a respondent to search for the correct answer.

- Make sure you do not give hints about the correct answer to other items on the instrument.

Attitudinal Items

-

- Avoid “loading” the questions by inadvertently incorporating your own opinions into the items.

- Avoid statements that are factual or capable of being interpreted as such. Make sure you do not give hints about the correct answer to other items on the instrument.

- Avoid statements that are so extreme that they are likely to be endorsed by almost everyone or almost no one.

- Statements should be clearly written -- avoid jargon, colloquialisms, etc.

- Each item should focus on one idea.

- Items should be concise. Try to avoid the words “if” or “because,” which complicate the sentence.

- For examples, please see this Likert Scale Guide created by the ASU Assessment & Research Office.

Psychometric Properties

Whether selecting a preexisting instrument or designing a new one, it is crucial to evaluate the reliability and validity of the instrument. A broad overview of both concepts is provided below. If you are a JMU employee in the student affairs division and would like to learn more, or need assistance evaluating the reliability and validity of your own instruments, schedule an appointment to meet with a SASS consultant.

Reliability refers to the consistency of scores. We are often interested in one of three types of reliability: internal consistency reliability, inter-rater reliability/agreement, and test-retest reliability.

Internal Consistency - Internal consistency reliability is concerned with the consistency of students' responses across items on the same test. The logic behind internal consistency reliability is simple: if all of the items on a test are believed to measure the same knowlede or skill, then students should respond similarly to the items. In other words, a high-ability student should score relatively high on most items, and a low-ability student should score relatively low on most items. If this is not the case, we may question whether the test is providing meaningful information. The most commonly used index of internal consistency reliability is coefficient alpha. Scores closer to 1 indicate higher reliability.

Inter-Rater Reliability/Agreement - When evaluating a product or performance using a performance assessment, it is desirable to have more than one rater rate each product/performance to reduce potential rater bias. When more than one rater is used, however, it is possible that their ratings might disagree. This is problematic because it introduces uncertainty about the true competency of the student being rated. Inter-rater reliability/agreement indices are useful in this situation because they indicate the degree of similarity between scores from multiple raters. Scores near 1 are desirable for the majority of these indices, as they indicate that raters agree more often.

Test-Retest Reliability - Test-retest reliability refers to the consistency of scores from one time to another one, or one test to another. High test-retest reliability is necessary if we want to use multiple forms of the same test (e.g., introducing a stort version of a lengthy test), or if we plan to collect data at one time point and use it to make decisions at a much later date (e.g., using junior year SAT scores to determine college math placement).

Validity is defined as the degree to which evidence and theory support the interpretations of test scores for proposed uses of tests1. From this definition we can draw three important conclusions:

1. Validity is a process of accumulating evidence. It may be helpful to think about this process as one that mirrors the scientific method: we start with a theory about the validity of our instrument for some purpose (e.g., the Alcohol Use Scale (AUS) is a valid measure of student alcohol use). Based on this theory we then construct a testable hypothesis (if the AUS measures alcohol use, it should be positively correlated with the number of alcohol-related hospitalizations and sanctions that are reported to the student conduct office). Finally, we design a study to test our hypothesis and determine the extent to which our theory is supported based on the results. Just like with the scientific method, the more “tests” we conduct, the stronger the support for our theory (i.e., the validity of our instrument for some purpose).

There are five types of validity evidence instrument developers typically collect: evidence related to test content, response processes, internal structure, relations to other variables, and consequences. For more information about these types of validity evidence, check out our comprehensive guide to selecting and designing instruments.

2. Validity is a matter of degree. Although it is common to hear test developers claim their tests are "valid and reliable," validity is not a benchmark that can be "reached." Determining whether an instrument is valid for a given purpose requires a holistic, subjective judgement that takes into account all of the evidence that has been collected.

3. Validity is concerned with how we interpret and use scores. Another reason it is problematic to call an instrument "valid" is that validity is not a property of instruments; the validity of an instrument depends on how we interpret and use its scores. For example, there may be strong validity evidence to support using the AP Calculus exam for college math placement, however, there would probably be less validity evidence to support using the AP Calculus exam scores for general college admission.

1American Educational Research Association, American Psychological Association, & National Council on Measurement in Education, & Joint Committee on Standards for Educational and Psychological Testing. (2014). Standards for educational and psychological testing.Washington, DC: AERA.

Integrating AI (Instrumentation)

Generative AI tools like ChatGPT and Copilot can support your thinking as you develop, evaluate, and refine assessments for your programs. In this section, we give you key assessment questions to answer during the instrumentation stage, alongside human expertise and validated evidence. AI is a starting point for supporting instrumentation, it is not a final authority. Always be sure to validate with human expertise and scholarly sources.

As an educator, how would you measure outcomes in your program?

You may use ChatGPT or Copilot to brainstorm how your outcomes might be observed or measured. You can upload program goals and ask:

- What styles of assessment work for these outcomes?

AI can help you generate a list of ideas (e.g., rubrics, surveys, reflections, behavioral indicators) that align with your program’s goals. AI may also indicate which constructs can be measured directly or indirectly.

What evidence exists that the measure accurately reflects the intended outcome?

You may use ChatGPT or Copilot to ask:

- Do these items match the goal of this outcome?

Scopus AI may also be useful to find and summarize research that links your outcomes to existing validated or theoretical frameworks. Though AI is helpful, SASS still recommends you refer to the repositories on our site to find pre-existing measures.

How does the measure function for different groups of students?

Generative AI tools can flag potential biases in item wording or assumptions. You might ask:

- Does this question include assumptions about culture, ability, or identity?

- Are there any parts of this item that would unfairly advantage or disadvantage a group of students.

!!! Note: AI may miss critical biases, especially those impacting marginalized groups. Use it to prompt your thinking, but not as your final check. Rely on research and professional reviews to ensure fairness. !!!

Is the measure sensitive to program impact? Is it sufficiently difficult to reflect program impact?

These questions prompt you to consider:

- Whether your tool can meaningfully detect student growth

- Whether it challenges students enough to make that growth visible

You may also use AI to reflect on the quality and relevance of your measure, including:

- Whether the measure is appropriate for the construct being assessed

- Whether it helps facilitators differentiate between students

- Whether it can identify changes in students’ knowledge, attitudes, or abilities.

What evidence exists that the measure produces scores that are reliable and support valid inferences about student learning or development?

Existing measures:

Where to start:

- Begin with the measures repositories available on the SASS website

- You may also use scholarly sources (e.g., JMU Libraries and Google Scholar) to find existing evidence on the measure

If you find a scholarly article but are unsure how to interpret it, AI can help you understand terms like reliability, validity, and factor analysis.

!!! Note: AI is not a replacement for expert review. Always consult an assessment professional or refer to expert reviews of measures before finalizing your decision. Do not rely on AI. !!!

Developing an instrument:

You may use AI to:

- Suggest edits for clarity or alignment

- Draft preliminary versions of new items

- Conduct backwards translation

!!! Note: Review all AI-generated content carefully, even small wording changes can impact the validity of your items. Treat AI as a tool for drafting, not for making final or high-stakes decisions. !!!

It is important to remember:

- AI is a thinking partner, not a validator

- Always prioritize evidence-based practices, fairness, and human expertise

- Poor assessment practices can lead to harmful or inequitable outcomes

- Use the SASS resources and repositories as your foundation.

Additional Resources

- Video: Selecting/Designing Instruments

- Handout: Overview of Selecting/Designing Instruments

- Handout: How to Find Pre-existing Instruments

- Handout: Comprehensive Guide to Selecting and Designing Instruments

- Slides: Overview of Writing Instrument Items

- Slides: Item Writing Workshop

- Video: Designing and Using Rubrics

- Article: "What's a Good Measure of That Outcome?"

-

Article: Identifying Measurement Instruments