Observational Protocols

Assessing the outcomes of a program can be a difficult task depending on its (the program’s) structure. Sometimes, program outcomes are behavioral in nature (e.g., leadership behaviors, networking abilities, peer mentorship). In these cases, a written test or a self-report assessment would be inappropriate to measure a behavioral outcome. Instead, this outcome might be best assessed through observation. To gather the most authentic outcomes data, student affairs professionals should employ an observational protocol. On this page, you will consider some questions like the following:

- How do we create measures to assess the desired behavioral outcomes?

- How can we execute an observational protocol? Is there a “right way” to observe?

- What considerations might improve the data we get from an observational protocol?

Observational Protocol: What is it? Why use one?

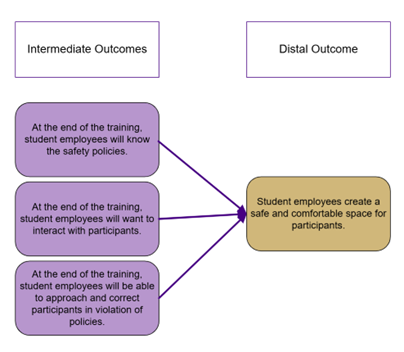

Observational protocols are surveys, checklists, or structured guidelines used to assess behavioral outcomes. It could be helpful to think about more specific situations in which we might want to develop an observational protocol. For example, let’s look at the abridged logic model below:

Our distal outcome is that student employees create a safe and comfortable space for participants at the university recreational center. We have three intermediate outcomes that we believe will contribute to our distal outcome:

- Student employees will know the safety policies.

- Student employees will want to interact with participants.

- Student employees will be able to approach and correct participants in violation of policies.

We create a training program for new student employees that addresses our intermediate outcomes. After the program, we can administer a quiz asking students to recite policies (what they will know), administer a self-report attitudinal measure to record student employee willingness to interact with participants (what they will think), and conduct a performance assessment during which student employees pretend to approach a participant (what they will do). We have successfully created measures to assess our intermediate outcomes.

But what about our distal outcome? In this case, our distal outcome is behavioral and, luckily, we can assess it, which may not always be the case. For example, we would be unable to assess the following distal outcome: “Students will engage in safe sex policies.” To address our example distal outcome, we want to see student employees in a real-world context. The best way to assess this distal outcome is through an observational protocol.

In this example, the distal outcome was behavioral, measurable, and focused on student employees creating a safe environment for participants. However, observational protocols can be used on intermediate outcomes as well. To include both types of outcomes, we will call them behavioral outcomes going forward. Some other example behavioral outcomes that may necessitate an observational protocol may deal with leadership skill expression, class participation, networking, peer mentorship, cultural sensitivity, group collaboration, and many others.

How do we know if an observational protocol is the best way to measure an outcome? Consider whether other forms of assessment (e.g., written test, self-report measure, performance assessment) appropriately measure our outcome. If not, we may want to put together an observational protocol.

What does an Observational Protocol look like?

Observational protocols can take many forms depending on the environment and behavioral outcome of interest. Below, we will look at a few different styles and examples of protocols. These designs can provide guidance when thinking about what kind of protocol may suit our needs.

Let’s review three main types of observational information we can gather.

- Holistic Observation: In holistic observation, we collect information after behaviors are performed. Typically, this involves reviewing a session (either live or via video recording) in its entirety and providing ratings on a set of criteria.

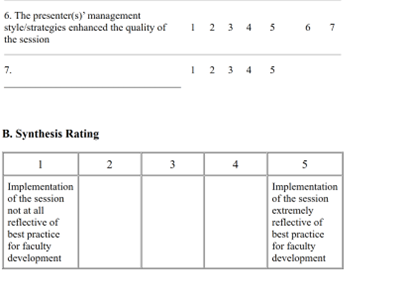

Here is an example from a protocol designed for teaching evaluation. Consider an example in which our outcome looks as follows: “Graduate students will facilitate professional development programming like a faculty member.” We record the faculty professional development opportunity. After the program ends, the observer uses the above items to determine the degree to which facilitation mimicked that of a seasoned faculty member.

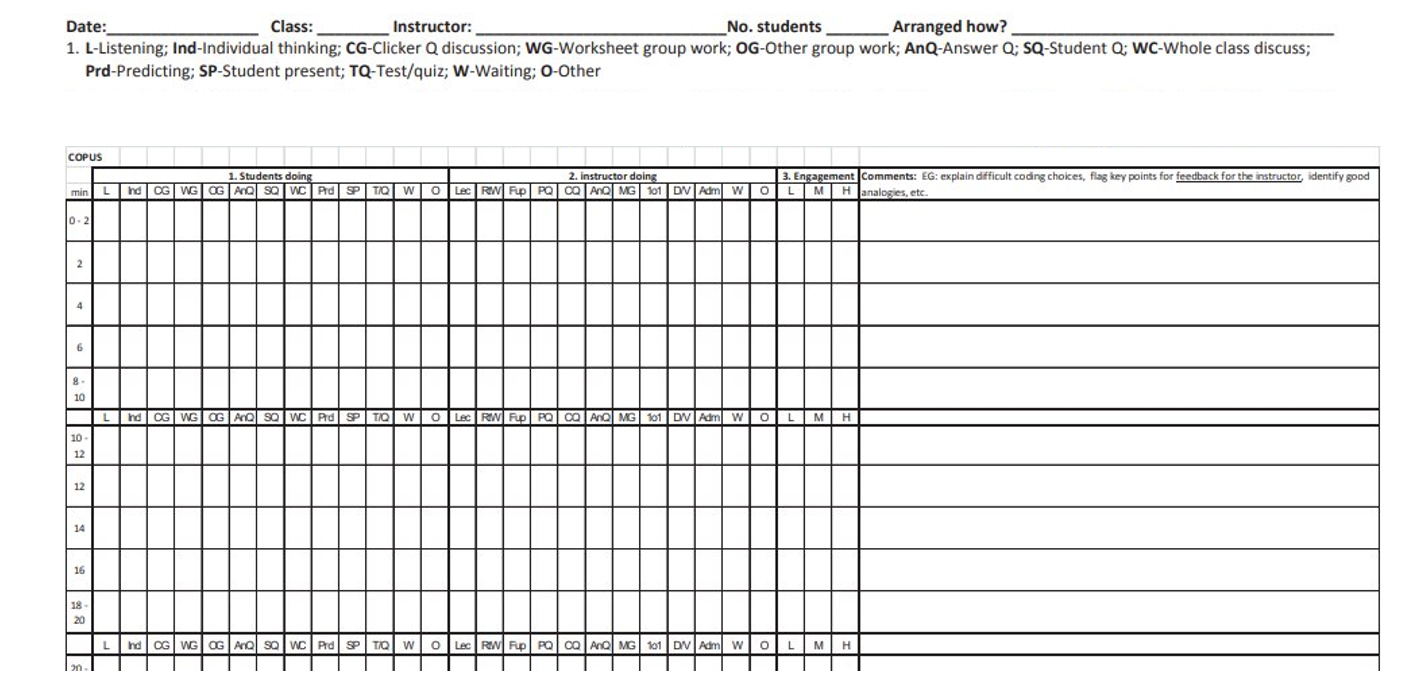

- Segmented Observation: In segmented observation, you would collect information by tallying a set of behaviors as they occur within specific time intervals. For example, let’s say our desired behavioral outcome is dynamic student engagement in a classroom setting. This behavioral outcome may be best measured through a segmented observation during which we would count how many times certain behaviors (often from a predefined list) occur during smaller chunks of time.

This protocol is the Classroom Observation Protocol for Undergraduate STEM (COPUS). In this example, we would document what behaviors (listening, individual thinking, clicker Q discussion, etc.) were observed in the classroom both with tallies and comments in intervals of two minutes.

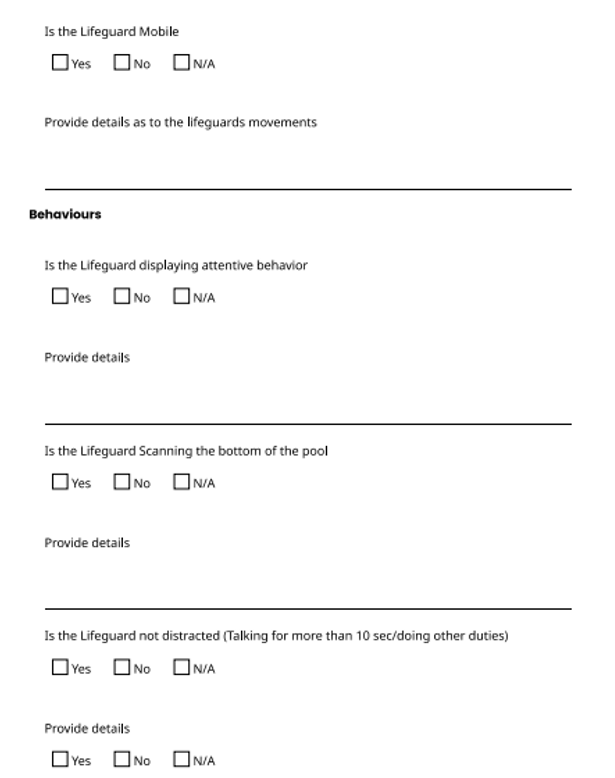

- Continuous Observation: In continuous observation, we would collect information throughout the observation period. Although segmented observation is also completed in real-time, continuous observation does not have restrictions of time intervals. As a result, protocol items might be broader or require consideration of the observation period at large. Suppose our behavioral outcome is that student employees engage in the expected behavior of expert lifeguards. After the training, we want to assess our behavioral outcome of expert lifeguard behavior on shift. We can use a continuous observation design for our protocol.

This is a Lifeguard Observation checklist. Lifeguard behavior is actively observed during the student’s shift. This protocol requires us to document the behaviors of the student lifeguard and add comments to provide details.

After deciding on the type of observational protocol, we need to decide how we will go about observing the desired outcome in a real-life environment. Here are four roles we might play as observers in an observational protocol:

- Complete Observer: The observer is not seen by participants and is completely detached from the environment under the protocol.

- Observer as Participant: The observer may be recognized or well known by participants; in fact, participants know the overarching goals of the observer. Observers and participants may interact, but this interaction is kept limited to maintain the natural flow of the environment.

- Participant as Observer: The observer is fully engaged with participants as opposed to a third-party individual. Observers and participants fully interact; participants are fully aware of the observer’s intentions.

- Complete Participant: The observer is fully embedded in the environment with the participants. In this format, the observer is like a spy. Participants are not aware of the observer’s intentions.

When selecting a method of observation, we must think through the ethical implications of our assessment. For example, electing to bring in observers as complete participants in the protocol may provide the best data on the desired outcome, but it can also be deceptive. We must pay close attention to the consequences of observation; reprimanding someone who was unaware of observation would be inappropriate without extenuating circumstances.

Important Considerations for Designing/Choosing a Protocol

At this point, we should have some ideas about the type and method of implementation for our observational protocol. Let’s use an example we used before in which a training program is administered with a behavioral outcome that reads “Student employees create a safe and comfortable space for participants.” We decide to use continuous observation (collecting information continuously throughout the observation period) and we bring in students to be complete participant observers (observers who are fully embedded in the environment with the participants). Now, it is time to either design an observational protocol or select an existing one. No matter which strategy we choose, we must keep in mind several key considerations as we design or select an existing observational protocol.

The following factors can give us PIECE of mind:

Purpose. The goal of an observational protocol is to assess outcomes through observed behavior. These protocols allow us to see desired outcomes in real-life environments. Using our example, student employees signing-in before their shifts might be important to us, but should this item be included in the protocol? Does observing this behavior concern the safety of participants? Keeping the overarching-goal in mind will help keep items on the protocol centered.

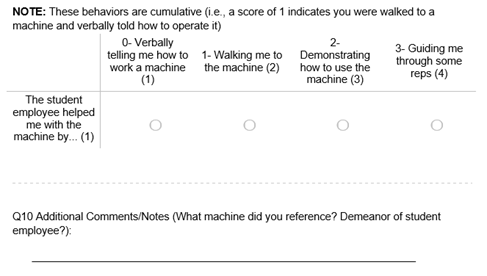

Item Type. Consider using a variety of items in our protocol. Variety may refer to the nature of the item like qualitative versus quantitative data. Try to achieve a balance between quantitative measurement (detail-lacking, easy to analyze) and qualitative measurement (detail-rich, more demanding to analyze). Variety may also be achieved within quantitative data collection. For example, we may decide to include a checklist (did/did not do) or items that ask for the magnitude or degree of a behavior (Likert-scale). Check out the example section of a protocol below:

We will get quantitative information (score of 0 to 3) from the Likert-scale regarding the student employee’s method of assistance. The question could have asked, “Did a student employee help you?” with a yes/no response option for the observer. However, this question would not tell us the degree to which help was provided. For our program, we felt it important to distinguish between verbal instruction and physical demonstration.

Additionally, we will get qualitative information from asking for more comments. Here, we might discover the student employee demonstrated how to use a machine but had a rude demeanor, which might deter other participants from asking for assistance and lead to safety issues. Using different types of items in our protocol is important for this reason.

Ease of Use. We must put ourselves in the shoes of the observer (whether that is us or someone else in the case of our example) when designing or selecting an observational protocol. We want to make our protocol as easy to use as possible. Observers face several different outside influences when performing an observation. The less required of observers in recording information during the protocol, the easier it will be for researchers to get the information of interest.

Think about what an observer is being asked to perceive. What might get in their way and how can we make our protocol so that some of these issues can be avoided or minimized? In our example, if our observer needs to make contact with a student employee, will giving the observer a full script make it harder to create an authentic interaction? Using shorter cues might help our observer better engage with student employees.

Lastly, we must be willing to adjust the protocol during data collection. Perhaps an unforeseen circumstance impedes the observer’s ability to carry out the protocol as designed; change the protocol so that the observers are better able to get the desired data. As a reminder, we may be the observers for our own protocol; make the protocol something you can use!

Clarity. What defines “quality?” In our example, what does a safe space for participants look like? How do student employees contribute to that? An observational protocol can be used to assess these outcomes, but they need to provide the necessary detail to observe if a behavior occurs, to what extent a behavior occurs, and the quality of the observed behavior. The clearer we can define what we are looking for, the easier it will be to find or develop a protocol that is effective. In our example, suppose one of our protocol items asks, “Was the student employee friendly?” What does “friendly” look like? Are there words or mannerisms that convey a student employee was “friendly?”

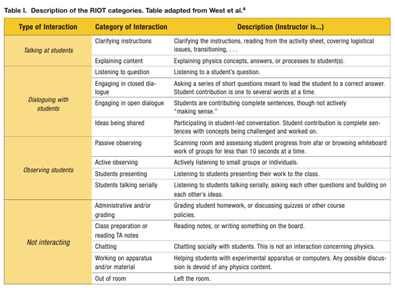

Creating a table or chart to clarify our behaviors of interest and specify what they look like can be helpful. Let’s consider a different example. Suppose our outcome is “Students will engage with instructors for the majority of a class period.” We administer programming to achieve this behavioral outcome. Before preparing our observational protocol, we put together the following table:

This table is from the Real-time Instructor Observing Tool (RIOT). Before enacting the observational protocol, we took the time to define the behaviors of interest. We include three columns of details: “Type of Interaction,” “Category of Interaction,” and “Description (Instructor is…).” Had we stopped at the first column, it would be difficult to discern the behaviors that would qualify “talking at student.” Had we stopped at the second column, it would be difficult to discern what qualifies passive versus active observation. The clearer we can articulate desirable (or undesirable) behaviors for our observers, the more accurate our protocol data will reflect our environment of interest.

Evaluation. What kinds of inferences or assertions are we able to make with our collected data? In our student employee example, where we are interested in upholding participant safety, are two open-ended comment boxes sufficient to make any statements about student employees changing shifts? It is just as important to think about our desired inferences after the protocol as it is to think about data collection before the protocol. Additionally, getting outside feedback on the method of data collection can be helpful. We may also have external personnel review our plans based on the data collected.

Important Considerations for Observers

To execute an observational protocol, we need to consider our observers! The protocol defines whether we are conducting the observation. Regardless, we should keep in mind a couple key questions that might remind you of the considerations in our PIECE acronym (Purpose, Item-type, Ease of use, Clarity, Evaluation). The difference in these questions is they are exclusively about the observer experience while the elements of PIECE deal with protocol design or selection (excluding Ease of use). When putting together an observational protocol, we wear the hats of both the developer/researcher and the observer to get the best data. So, what questions should we ask when considering the observers?

- Who are my observers?

- If our protocol requires observers to be covert, avoid observers with a conflict of interest. If observers are instructors or supervisors of those being observed, it might bias observer scores or alert those being observed with the protocol. Either way, it is best to check-in with observers prior to implementing the protocol. If we are the observers ourselves, we should approach the observation as objectively as possible.

- Also consider the quantity of observers that are necessary. A smaller group of observers can make the training process easier. A smaller group will be best acquainted with the protocol and will be more consistent with their scoring. A larger group of observers presents concerns about scoring consistency and training. However, availability for scheduling, remaining undetected in the observed environment, and representation of different viewpoints can be better in larger pools of observers.

- Do our observers know how to use our protocol?

- Ensuring our observers are familiar with the protocol is essential to gathering observation data. A behavior listed in the protocol may mean one thing to one observer, but a different thing to another observer. This idea goes back to the C in PIECE: Clarity.

- Conducting a training with the protocol is often the best way to make sure observers are comfortable with the instrument. During the training, we can eliminate any areas of confusion. We can show observers how to use the instrument. If we ask for open-ended comments in the protocol, what kinds of comments are useful? What information is unimportant?

- It might be useful to pilot the protocol beforehand in case observers find a way to improve efficiency or notice a behavior that was not yet considered. Including a debriefing session both in the pilot and when executing the protocol can allow for feedback for both the researchers and the observers.

- How should we organize our observers?

- Planning and scheduling the execution of a protocol takes additional consideration. How many observations do we need to get the data of interest? The quantity of observations should be representative of different times and climates in our environment of interest. Consider the type of analyses we want to perform with the resulting data. Five observations may be suitable for qualitative data analysis, but we may need more observations for quantitative analysis.

- We must define the length of observations which will be largely dependent on the desired outcome. We might need a longer session if the behavior takes time to unfold. While longer observations might gather more data in a single session, shorter observations may yield more authentic results given observer fatigue. The length of observations should be both conscious of observers and of the frequency of the desired outcome.

- Also, we might want to decide how often each participant is observed. Consider whether an outcome requires a pre/post data collection setup or a singular data collection point after program completion.

Putting it All Together

In the end, no “right way” exists to create/select or carry-out an observational protocol. The goal of this page was to highlight some different decisions we might want to make and get us asking questions that can help finetune our protocol. However, walking away with tangible steps is always helpful; consider the following:

- Decide how we want to observe.

- What type of protocol are we using?

- Decide how we are able to observe.

- How do we want to observe the environment?

- Design or choose a protocol.

- Consider PIECE of mind.

- Determine who the observers will be.

- How many observers do we need?

- Determine how we should use our protocol.

- How should we train our observers?

- Determine when we should use our protocol.

- At what time should we use our protocol?

Additional Resources

Article (30 Essential Skills for the Qualitative Researcher): Creswell (2016)

Webpage (Measuring U): 4 Types of Observational Research

Article (A Primer on Observational Measurement): Girard & Cohn (2016)

Article (Reconsidering the Value of Covert Research: The Role of Ambiguous Consent in Participant Observation): Roulet, Gill, & Gill (2017)