By Elizabeth R. H. Sanchez (‘15M)

University wide learning improvement initiatives are rare—most faculty at James Madison University use assessment results to modify a single section or course that fit into the broader curriculum. But what happens when there is no particular course or section to modify? No curriculum that is housed in the four walls of a typical JMU classroom? What if the skills are Information Literacy —always evolving with new technologies and essential for every student, in every aspect of their collegiate studies? Assessing all JMU students with new measures, making changes to online material, and collecting more data to certify that the targeted changes led to improvement is an achievement reserved for only the likes of Kathy Clarke and her supportive Information Literacy team.

As with many programs on campus, the foundation for Information Literacy skills development and assessment was laid long before Clarke arrived at JMU. The re-structuring of General Education, campus-wide implementation of measurable objectives, and a dedicated predecessor, Lynn Cameron, created for Clarke an ingrained work ethic centered on improved student learning. Clarke, librarian and professor at JMU, enthusiastically collaborates with a dedicated team of supportive JMU administrators, “the powerhouse that is CARS [the Center for Assessment and Research Studies]” which includes assessment liaisons Dr. Jeanne Horst and Dr. Christine DeMars, General Education Cluster One Coordinator Gretchen Hazard, and innovative Communication Studies professors such as Dr. Tim Ball to create better learning opportunities for students.

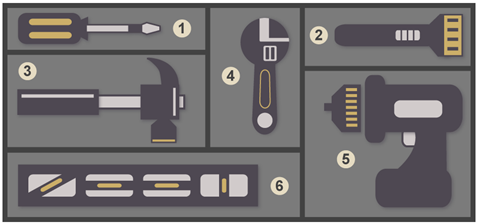

Information Literacy skills are articulated through six student learning outcomes (SLOs) adopted from the Association of College & Research Libraries’ (ACRL) Information Literacy Competency Standards for Higher Education. In order to be deemed competent in Information Literacy , JMU students must: (1) recognize that information is available in a variety of forms including, but not limited to, text, images, and visual media; (2) determine when information is needed and find it efficiently using a variety of reference sources; (3) evaluate the quality of the information; (4) use information effectively for a purpose; (5) employ appropriate technologies to create an information-based product; and (6) use information ethically and legally.

However, there is no traditional course that is structured around Information Literacy skill development, so Clarke and team have created an online curriculum: a series of six tutorial videos (The Madison Research Essentials Toolkit) for students to watch and learn before taking a required direct measures assessment, the MREST: the Madison Research Essential Skills  Test. In the past, data revealed that not many students were successful at mastering Information Literacy skills—which are part of General Education and are mandated by the State Council of Higher Education in Virginia (SCHEV). In hopes to ensure students continue to learn these valuable and mandated skills and improve over the course of time, Clarke and team set up plans to make a major change to the online curriculum and assessment measures. As Horst mentioned, there exists intrinsic value for program improvement “there isn’t always an understanding [of required assessments],” but, she says re-assuringly, “once people see the value, they become engaged.”

Test. In the past, data revealed that not many students were successful at mastering Information Literacy skills—which are part of General Education and are mandated by the State Council of Higher Education in Virginia (SCHEV). In hopes to ensure students continue to learn these valuable and mandated skills and improve over the course of time, Clarke and team set up plans to make a major change to the online curriculum and assessment measures. As Horst mentioned, there exists intrinsic value for program improvement “there isn’t always an understanding [of required assessments],” but, she says re-assuringly, “once people see the value, they become engaged.”

The process of changing (and continuing to modify) Information Literacy content and delivery was (and is) not a simple one. In fact, Clarke and her colleagues faced considerable challenges in the assessment, modification, and re-assessment processes. For instance, because students were not scoring well the MREST and the content of the online curriculum was becoming outdated, Clarke felt that the Information Literacy skills team needed to change both the program and the test—but re-creating videos suitable for all JMU students and crafting a new assessment instrument that provided valid and reliable data are both tremendously time intensive tasks.

The development of a new measure: the Madison Research Essential Skills Test (MREST) is an accomplishment in-and-of itself. Clarke took it upon herself to update the MREST during her time in the JMU Assessment Fellows Program. As with most faculty at JMU, Clarke learned the foundations of how to assess students through her involvement with CARS—a center that is one of the most advanced in the nation. Although she knew the Information Literacy content and had an idea of how to update the assessment measure, Clarke noted that the commitment of CARS and the atmosphere of student learning at JMU were invaluable resources in her quest for programmatic improvement.

But, it is important to point out that it took much more than trying to perfect the MREST to change how much students know about Information Literacy; improvement in student learning can only occur after a change is made to the actual program. As Horst notes, when discussing how assessment data is used, “it’s so easy to talk about the instrument.” However, Clarke’s experiences with Information Literacy demonstrate that modifying the assessment processes and curriculum “is a balancing act” in which student learning improvement is the ultimate goal—and measure of success.

In fact, the first year of students completing the new MREST did not score well on the test. However, to Clarke, the results were not that surprising: only the content on the MREST was revitalized. Without time to change the online curriculum, the Toolkit tutorials taught students content not included in the revised test. But, Clarke and her colleagues did not give up in their efforts for improvement—actually, this less than desirable “experience that greased the wheel” incentivized a team of librarians to re-design the online curriculum using the same established learning outcomes and content as the MREST.

According to Clarke, establishing clear objectives in the recreation of the test and Toolkit tutorials was one of the most important parts of the process; one that was critical in creating alignment and thus, improving scores. In fact, every year since the re-creation and re-alignment of the Toolkit and MREST, data show enhanced student learning—but the dedication to improvement has not stopped there.

Now, the student learning data is continuing to nuanced show improvements—students taking a course embedded with Information Literacy skills are scoring higher on the MREST compared to students without Information Literacy coursework; results that demonstrate that the new curriculum, paired with proper sequencing, achieves what SCHEV and the standard-setters at JMU had hoped to accomplish in regards to what students should know, think, or be able to do. This data, too, provides support for future pairing of Information Literacy and other content in major programs. The student learning improvement process is never really over for Clarke, Horst, and others working on Information Literacy skill development. New standards, information delivery methods, and desired competencies change with time—all factors that Clarke and team must take into consideration when making modifications. JMU’s supportive environment, Clarke’s personal investment, the dedication and power of CARS, and demonstrated student learning improvement—makes the collaboration a stand out among programs nationwide, an acknowledgement that is well deserved.

Now, the student learning data is continuing to nuanced show improvements—students taking a course embedded with Information Literacy skills are scoring higher on the MREST compared to students without Information Literacy coursework; results that demonstrate that the new curriculum, paired with proper sequencing, achieves what SCHEV and the standard-setters at JMU had hoped to accomplish in regards to what students should know, think, or be able to do. This data, too, provides support for future pairing of Information Literacy and other content in major programs. The student learning improvement process is never really over for Clarke, Horst, and others working on Information Literacy skill development. New standards, information delivery methods, and desired competencies change with time—all factors that Clarke and team must take into consideration when making modifications. JMU’s supportive environment, Clarke’s personal investment, the dedication and power of CARS, and demonstrated student learning improvement—makes the collaboration a stand out among programs nationwide, an acknowledgement that is well deserved.

Clarke would also like to acknowledge that this continued work is made possible by the assistance she receives internally from her instruction librarian peers (notably Liz Thompson and Bethany Mickel); the video support from JMU’s Center for Instructional Technology (CIT); and all the JMU liaison librarians who are invested in this work, as they all set the stage for what Information Literacy in major programs can scaffold upon given the work that has occurred in the first year.