Community-Engaged Learning, often called Service-Learning or Community Based Learning, is a pedagogical approach to teaching courses that integrates community engagement into coursework instruction and reflection to enrich the learning experience, teach civic responsibility, and strengthen communities.

This approach to education rests on the following assumptions:

- The community, in all its diverse forms, is at the center of learning and engagement

- Partnerships are mutually beneficial; everyone involved contributes knowledge, skills, and experience to address community priorities

- Intellectual accountability through critical reflection is essential at every phase of the experience

- Positive outcomes for the larger community, student learning, and student civic engagement are fundamental

JMU faculty have been using this pedagogy as a unique form of engaged learning since the 1980's in our local, national, and international communities.

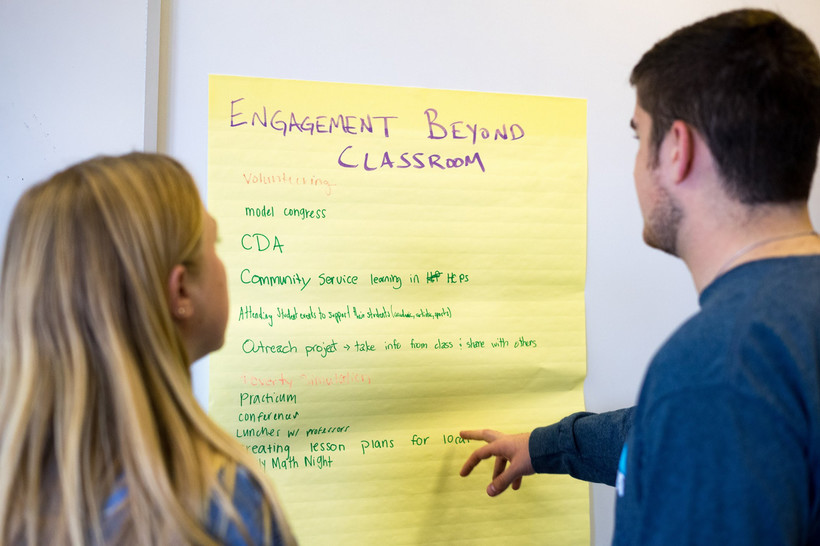

Types of Engagement

Community-Engaged learning (CEL) design and practice can vary widely (direct, indirect, research, or advocacy). Consider the JMU examples below. Engagement can be designed so that each individual student works with CEVC to select a community partner consistent with faculty expectations. In time-oriented models, students are expected to complete a specific number of hours in the community. 20-30 hours over the course of the semester is optimal for most 3 credit courses. In a project-oriented model, the class can work as a whole or in small groups to address the priorities of one or more community organizations serving as “clients” for the course. CEL can also take place over a student break, known as an Alternative Break, or engagement can be episodic in nature or scheduled around community events. Even one-day service can be learning oriented. Many faculty members start with a limited or optional community engagement component and build their commitment in future semesters.

- Art education students teach art classes at Virginia Mennonite Retirement Community to independent living and memory care (Karin Tollefson, ARED 302).

- Students serve with the Committee for the Upliftment for the Mentally Ill (CUMI) in Montego Bay, Jamaica, as part of an Alternative Spring Break integrated into SOCI 385: Madness and Society (Kerry Dobransky). For the duration of the week, students interact with individuals experiencing mental illness and homelessness and lead a variety of enrichment activities.

- Students work with the Caregivers Community Network to provide care and support a few hours each week to folks in hospice or home healthcare environments (IPE 490, Kathy Guisewite).

- Students work with local small-scale farmers to identify and implement more sustainable farming practices (Jennifer Coffman & Wayne Teel, ISAT 473).

- Students organize PR campaigns for local nonprofit organizations (Shana Meganck, SCOM 461).

- Students learn the scope of the grant-writing process while compiling materials and writing narratives for future grant opportunities as well as serving as grantors awarding two grants each semester to partners (Laura Trull, SOWK/FAM/NPS 375).

- Students research and create written materials within health science contexts with a variety of partners (i.e., IIHHS, Valley Program for Aging Services, Claude Moore Precious Time, etc.) each semester (Michael Klein, WRTC 488).

- Students work with the Blue Ridge Area Food Bank to create story maps to demonstrate community areas of concern in more accessible ways.

- Students apply design thinking and systems approaches to create innovative ideas to address wicked problems in X-Labs Community Innovations, a transdisciplinary course (PUAD 584/PPA 483 [Rob Alexander], NPS 487 [Jamie Williams], MATH 428 [Dinesh Sharma], X-Labs [Aaron Kishbaugh], and WRTC 328 [Seán McCarthy].

- Students help manage a feminist blog, ShoutOut! JMU (Kathryn Hobson, SCOM 301).

- Following an Alternative Spring Break in Joshua Tree National Park, student leaders organize a letter-writing party to share their experience with elected officials and advocate for policies they support related to the National Park Service and climate change.

- Transdisciplinary student teams research and design interventions to address issues within political representation. These groups assist with mobilizing “Get Out The Vote” initiatives on campus (Carah Ong Whaley, POSC 351, X-Labs Hacking for Democracy).

Theoretical Foundations

The theoretical roots of this pedagogy are typically attributed to John Dewey, an early champion of experiential education. While Dewey’s scholarship on reflective thinking was undoubtedly influential, there were countless voices that contributed to the field that are too frequently overlooked. When the history of the field is authored by academics, the influential contributors are likely to be published scholars with recognizable scholarly products (Dolgon, 2018). Neglected contributors include “feminist-pragmatists” (Deegan, 2018, p. 52) like Jane Addams, co-founder of the Hull-House in late 19th century Chicago who influenced Dewey, a faculty member at the University of Chicago at the time. Similarly, Historically Black Colleges and Universities founded on the heels of the civil war focused on “community engagement—typically expressing a commitment to social change and challenging social oppression” (Daniels, Hicks, & Plummer, 2018, p. 65). Our current understanding of the role of higher education in the community is shaped by scholars like Dewey as well as a rich, messy, and contradictory tapestry of activists, non-traditional educational institutions, and movements steeped in a deep commitment to realizing democracy.

At the core of this community engaged pedagogy is the notion of coupling community experience with the rich intellectual traditions of the academy to bring about societies that are fair and just. While experience can be a powerful learning opportunity, Dewey cautioned that some experiences are mis-educative and can unintentionally reinforce stereotypes. David Kolb’s Experiential Learning Model was built on the work of Dewey, Jean Piaget and Kurt Lewin, and has been a foundational theory since 1984 (Jacoby, 2015). To decrease the likelihood that experience will cement stereotypes, Kolb proposed linking intentional reflection with experience.

Service Learning (S-L) scholarship flourished in the 1990s and several theories and concepts still ground our approach today and caution us against uncritical acceptance that all community engagement is inherently good. In 1990, Nadinne Cruz challenged practitioners to flip their assumptions about communities on their heads by viewing the community through the lens of the community as opposed to faculty, staff, and students. John P. Kretzmann and John L. McKnight introduced the asset-based community approach in 1993 followed by Robert L. Sigmon’s typology of service and learning in 1994. In 1995, Keith Morton proposed a continuum of service paradigms and in 1996 Andrew Furco provided a helpful diagram to distinguish S-L from volunteerism, community service, field education and internships. 1999 brought the University of Maryland’s P.A.R.E. model and Where's the Learning in Service-Learning by Janet Eyler and Dwight Giles.

This pedagogy has continued to evolve in recent years. An emerging body of literature advocates a critical view of Service-Learning with an explicit goal of advancing social justice. In 2008, Tania Mitchell built on Paolo Freire’s 1970 Pedagogy of the Oppressed to distinguish “traditional” vs. “critical” S-L. The critical approach “re-imagines the roles of community members, students, and faculty in the Service-Learning experience. The goal, ultimately, is to deconstruct systems of power so the need for service and the inequalities that create and sustain them are dismantled” (Mitchell, 2008, p. 50). Recent work by Barbara Jacoby has also been broadly influential. Her 2014 book Service Learning Essentials is widely used as a guidebook and hard copies are available for interested JMU faculty. Most recently there have been debates about the degree to which this pedagogy acknowledges the political realities in communities and among our students. Should community engaged practice prepare students to address the most vexing problems facing our communities? If a community engaged practice is divorced from the systemic issues facing our students and communities, whose needs is it serving?

In recent years, language has shifted from Service Learning to the broader term, Community Engaged Learning to acknowledge that learning from and acting with community may include "direct service (think tutoring or serving meals), advocacy or activism (think registering voters or participating in organized demonstrations), participatory action research (think administering surveys or collecting oral histories to inform community change efforts), or simple solidarity (think talking and listening to people describe their struggles to resist oppression and honoring their lived experience)." (Donahue and Plaxton-Moore, 2018, p.4).

See our Scholarship section for current recommended readings, journals, and resources.