Ben Shahn: Art as Civic Engagement

To support JMU student civic engagement in the upcoming elections, this digital exhibition represents the collaboration of three separate entities: the James Madison Center for Civic Engagement, faculty from the School of Art, Design, and Art History, and objects from the Madison Art Collection.

The featured works by Ben Shahn, a prolific American artist who believed strongly in civic responsibility and art as activism, are drawn from the Madison Art Collection’s extensive Shahn holdings, thanks to gifts from Mr. Michael Berg and the Ben Shahn Estate. Dr. Laura Katzman, Professor of Art History in the School of Art, Design, and Art History provided scholarly text on the artist and individual works. The James Madison Center for Civic Engagement helped support the presentation of these works of art through the lens of 2020.

For more information on civic engagement, voting, and more, please visit Dukes Vote: Election Connection.

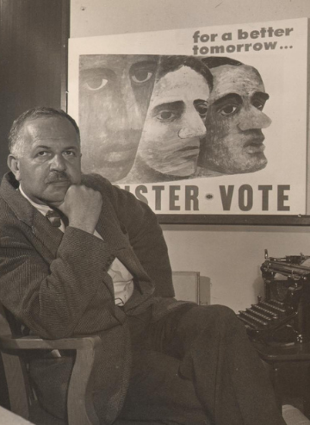

Ben Shahn (1898-1969) pictured in front of one of his labor posters urging people to vote.

Ronny Jaques (1910-2008)

Ben Shahn (CIO-PAC Office, New York City), ca. 1945

Gelatin silver print

10 x 10 9/16 in.

National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution

@The Estate of Ronny Jaques

Ben Shahn (1898-1969) is among the most prominent of the socially engaged, left-wing American artists who came to the fore between the onset of the Great Depression and the end of World War II. Born into a working-class, Orthodox Jewish family with whom he emigrated in 1906 from tsarist-controlled Lithuania to the United States, Shahn grew up in the poor yet ethnically rich immigrant neighborhoods of Brooklyn, New York. These densely populated, multicultural environments, especially those with vibrant Yiddish culture and leftist politics, deeply impacted his artistic sensibility. From the 1930s through the 1960s, Shahn was a politically progressive painter and graphic artist who worked for U.S. government agencies, labor unions, political campaigns, and civil rights and peace organizations, devoting his art to fighting what he perceived as injustice, marginalization, and persecution.

Shahn’s art remains relevant today as a model of civic engagement. He tackled subjects that he felt were a threat to national and global progress, and believed that artists have a special responsibility in society to respond, interpret, and give meaning to the worlds in which they live. This is best summed up in his 1953 essay, “The Problem of Artistic Creation in America,” in which he wrote:

"For life, seen and valued by the artist, emerges with new meaning. It is not just the artist’s experience, but his values, his judgments, made with love, or anger, or compassion, that live in the work of art and make it significant to the public. For they change and modify the public’s own values, and create meaning where there was none before."

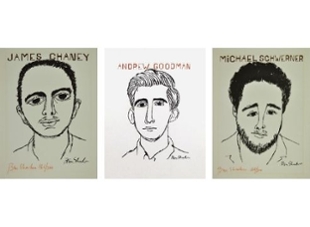

Ben Shahn (Lithuanian-born American; 1898–1969)

Human Relations Portfolio: James Chaney, Andrew Goodman, and Michael Schwerner, 1965

Photoscreen print in black and umber

Each: 15 7/16 x 11 7/16 in.

Gift of Mr. Michael Berg, 2014

Madison Art Collection, 2018.02.02, 2018.02.03, 2018.02.04

©Estate of Ben Shahn/Artists Rights Society, NY.

In the 1950s and 1960s, Shahn was an active participant in the American civil rights movement and a passionate proponent of the global struggle for equality. As a Jewish immigrant who experienced anti-Semitic persecution first hand, Shahn’s commitment to fighting racism was fueled by the experiences and lessons of his own heritage.

Shahn pictured several male martyrs of the civil rights era such as the icon of non-violence Reverend Martin Luther King, Jr. (1929–1968) as well as famous historical heroes like abolitionist leader Frederick Douglass (1818–1895). Among the artist’s most haunting images are these simple line portraits of three young civil rights workers, James Chaney, Andrew Goodman, and Michael Schwerner, who were brutally murdered in Philadelphia, Mississippi by the Ku Klux Klan on June 21, 1964. The images of the men (one Black and two white), who were all in their early twenties at the time of their murder, were based on news photographs. Part of the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) during “Freedom Summer,” they were involved in what was then the dangerous work of registering Black Southern voters.

Sold in portfolios enclosed with Edwin Rosskam’s text Martyrology, Shahn’s prints were used to raise money for the Human Relations Council of Greater New Haven, Connecticut. They served to memorialize the horrific killings and propelled President Lyndon Johnson’s support of Congressional enactment of landmark legislation on civil rights. Indeed, Johnson signed into law the Civil Rights Act on July 2, 1964 and the Voting Rights Act on August 6, 1965.

Ben Shahn (Lithuanian-born American; 1898–1969)

For All These Rights, We've Just Begun to Fight (REGISTER-VOTE), 1946

Offset photolithograph in colors; CIO-PAC poster.

29 x 38 3/4 in.

Gift of Ben Shahn Estate, 2015

Madison Art Collection, 2018.2.5

©Estate of Ben Shahn/Artists Rights Society, NY.

Between 1944 and 1946, Shahn served as chief artist and then director of the Graphics Arts Division of the Congress of Industrial Organization’s Political Action Committee (CIO-PAC). Established in July 1943, CIO-PAC aimed to circumvent the financial restrictions that unions faced in making contributions to political campaigns. Shahn’s posters—featuring figures with large, strong, and hard-worked hands—speak to the dignity of manual labor and to Shahn’s respect for craftsmanship, which he inherited from his family of woodcarvers. His posters express the centrality of labor issues to the Democratic Party at the time.

Shahn’s posters from 1944 were used to champion President Franklin Delano Roosevelt (FDR) for an unprecedented fourth term, presenting FDR as a friend of labor unions and conveying a hopeful, uplifting tone. In contrast, the posters from 1946, such as For All These Rights We’ve Just Begun to Fight, express more anxiety, even militancy. Made during the presidency of Harry Truman, who held less-than-firm support for organized labor, the poster suggests crisis and an embattled labor force, even foreshadowing the weakened position of organized labor in American society. For All These Rights refers back to FDR’s January 1944 Economic Bill of Rights speech; it shows a defiant figure with an outstretched arm, standing amidst colorful protest placards. The texts on these placards promote what Roosevelt’s New Deal administration saw as basic human rights: the right to a job, an adequate wage, a decent home, medical care, economic protection in hardship, and a good education.

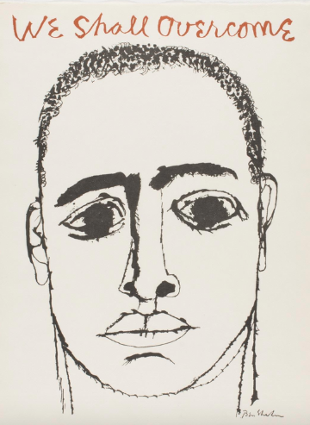

Ben Shahn (Lithuanian-born American; 1898–1969)

We Shall Overcome (Nine Drawings Portfolio), 1965

Offset photolithograph printed in black and brown

22 1/8 x 16 3/4 in.

Gift of Mr. Michael Berg, 2018

Madison Art Collection, 2018.2.6

©Estate of Ben Shahn/Artists Rights Society, NY

Another strong example of Shahn’s commitment to the struggle for social justice and racial equity is the Nine Drawings Portfolio (1965), which was “published and distributed as part of a fund-raising effort by the Lawyers Constitutional Defense Committee of the American Civil Liberties Union. The Committee was founded early in 1964 by legal officers of various civil rights and civil liberties organizations to provide legal representation in civil rights cases in the Deep South." Each portfolio was accompanied by a poem written by Edwin Rosskam and includes images promoting interracial solidarity and brotherhood, as well as portraits and tributes to civil rights leaders and martyrs. One of the two largest images in the portfolio depicts the face of an unidentified young Black man, above which Shahn wrote in cursive script: We Shall Overcome.

This powerful portrait is rendered in Shahn’s signature barbed-wire line that brings a compelling emotional charge to the image. The young’s man face is presented head on, as he stares intensely at the viewer with his large eyes, heavy eye brows, and a somber expression. His pensiveness is contrasted with the determination of the words above. The phrase references a song that became the unofficial anthem of the American civil rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s. As an avid follower of political folk music, Shahn knew well the version of the song made famous by Pete Seeger (1919–2014), who learned it in 1947 as a pro-union protest song from Zilphia Horton of Tennessee’s Highlander Folk School, which was dedicated to educating labor organizers and later civil rights workers.

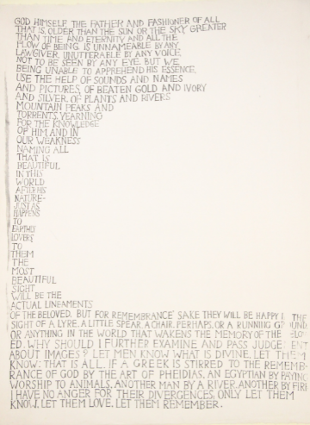

Ben Shahn (Lithuanian-born American; 1898–1969)

I Think Continually of Those Who Were Truly Great, 1965

Screen print in black and white; incomplete.

26.75 x 20.5 in.

Gift of Ben Shahn Estate, 2015

Madison Art Collection, 2018.2.7

@Estate of Ben Shahn/Artists Rights Society, NY

Shahn created this print as a tribute to the heroes or martyrs of the civil rights era, specifically the victims of racial terror that plagued Alabama in the 1960s. In the final version, for which MAC’s work is a study or incomplete state, the image features a peace dove above which Shahn wrote in a white, child-like cursive script the names of ten of these martyrs. These include the names of four Black girls who perished from a bomb blast set off by Klansman in September 15, 1963 at the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama: Denise McNair; Carol[e] Robertson; Cynthia Wesley, and Addie Mae Collins.

Below the bird’s open wing, Shahn wrote in his influential folk lettering a portion of the 1928 poem, I Think Continually… by the British poet Stephen Spender (1909–1995), who was noted for his devotion to social justice and class struggle. The last four lines of the poem poignantly express how Shahn saw those who gave their lives to the freedom struggle:

The names of those who in their lives fought for life,

Who wore at their hearts the fire’s centre.

Born of the sun, they travelled a short while toward the sun.

And left the vivid air signed with their honor.

In MAC’s incomplete version of the print, the image has no bird, only the names of the civil rights martyrs and the Spender poem. Due in part to Shahn’s rendering and placement of the texts, the print still carries the power of its message.

Text by Dr. Laura Katzman, Professor of Art History, James Madison University

For more on Ben Shahn, see Laura Katzman, Drawing on the Left: Ben Shahn and the Art of Human Rights (Harrisonburg: Duke Hall Gallery of Fine Art, James Madison University, 2017; second printing 2018).