JMU professor leads discovery of Hernando de Soto’s first campsite

Featured StoriesSUMMARY: After nearly 20 years digging into the story of 16th-century Spanish explorer Hernando de Soto, JMU anthropology professor Dr. Dennis Blanton and his team of researchers have made “the find of a lifetime.” In late October, he and several other experts and volunteers unearthed the pommel of a Spanish-made sword in the remnants of a Native American village in southern Georgia. It’s the latest in a vast collection of artifacts that Blanton says proves he has discovered the first-ever encampment along Soto’s march through the American interior in the year 1540.

Hear more episodes and subscribe to the podcast at the Being the Change podcast page.

For nearly 20 years, anthropologist and JMU professor Dr. Dennis Blanton has been digging into the story of Spanish explorer Hernando de Soto. Blanton’s goal had been to find physical proof of Soto’s time in present-day Georgia in the year 1540, during his multiyear quest for riches and greater information about the New World.

Now, almost 500 years after Soto marched through Georgia with 600 men and 250 horses, a small team of researchers has uncovered what Blanton is calling “the find of a lifetime.”

In late October, the team unearthed the pommel of a 16th-century Spanish sword — rare evidence that Soto not only traveled through rural southwestern Georgia, but also set up camp there with a small army.

The pommel — the end of a sword handle that’s crucial for counterbalance — is “one of those artifacts we only dreamed of finding,” Blanton said. “It’s absolutely electrifying.”

Blanton has been attempting to track the Soto expedition’s path for 18 years, ever since he identified artifacts on a separate site in south-central Georgia that he could link to Soto’s era. Now, after discovering a trove of 16th-century Spanish artifacts at a second location in Georgia, Blanton is making significant progress in his Soto studies. Before he began his work, there was no concrete proof of Soto’s passage between Florida and the Appalachian foothills of North Carolina other than records from his fellow explorers. Blanton said the site where he and other researchers have been digging near Albany, Georgia, is the first proven Soto encampment outside of Florida.

And yet, this landmark discovery might never have happened if not for a phone call from former Coca-Cola CEO Doug Ivester.

Searching for Soto

In 2007, Blanton was curator of Native American archaeology at the Fernbank Museum of Natural History in Atlanta, Georgia, when Ivester called to ask the museum’s president, Susan Neugent, if she would send someone to his country estate to examine the thousands of Native American artifacts that one of his employees had found. Eric Kimbrel, son of longtime land manager Mack Kimbrel, had filled nearly every flat surface in one of the plantation’s houses with Native American tools he had picked up around the property. But Blanton, who traveled there with Neugent, was more interested in the 5-gallon bucket of Spanish pottery the young employee had found while deer hunting.

Blanton already had Soto on the brain after a student researcher found a multilayered glass bead matching Soto’s time period on what’s known as the Glass Site, a good 80 miles from where most scholars believed Soto’s route would have taken him (through Macon, Georgia). Blanton saw this as a sign of imperfection in the accepted understanding of Soto’s journey among archaeological experts. His goal became explaining why there was evidence of Soto at a site where he wasn’t believed to have traveled. When Ivester called the museum, Blanton was in the process of documenting the numerous Soto-era artifacts he had not expected to find at the Glass Site starting in 2006.

“I knew that the area of Deer Run was one of those places people thought Soto might be, and that’s all I could think about on my first visit there,” Blanton said. “So that’s what started it really ... that unexpected invitation to examine Deer Run artifacts. And thank goodness. When Doug Ivester saw my excitement and asked, ‘Would you like to work here? Would you like to study?’ — I was like, ‘Are you kidding? Of course.’ And so, Doug says, ‘Why don’t you come back?’”

A few months later, Blanton returned to Deer Run Plantation with a team to start his research, but they didn’t find any Soto artifacts. In fact, it would be six more years before he saw anything there that he could link to Soto. “It took a little while,” Blanton said. “This was before I came to JMU, and it wasn’t until I came to JMU and began to bring our students to the site that we found Soto artifacts.”

Uncovering history

Blanton grew up in South Carolina before moving with his family to the small southeastern Georgia town of Alma. There, he attended Bacon County High School before earning his bachelor’s in Anthropology from the University of Georgia.

“It was a great time to be there,” Blanton said. “I was at the University of Georgia when one of my mentors rekindled Soto studies. ... The atmosphere was just thick with Soto, so I was sort of schooled in it.”

That mentor was the late Dr. Charles M. Hudson Jr., Blanton’s anthropology professor and a leading Soto authority. Around the same time, Blanton met longtime friend and colleague Dr. Chester DePratter through The Society for Georgia Archaeology. “I just wanted to breathe the same air as him,” Blanton recalled. Now a professor emeritus with the University of South Carolina, DePratter was one of several experts to attend the recent Deer Run dig.

As a graduate student at the University of Georgia in 1976, DePratter joined Hudson in researching Soto’s 1539-1543 American entrada and co-authoring several papers tracking the explorer across the American southeast before his death from a fever in 1543 along the Mississippi River. In 1983, Hudson and DePratter mapped Soto’s route with Dr. Marvin T. Smith, professor emeritus of sociology, anthropology and criminal justice at Valdosta State University in Georgia. Hudson included the map in his book, Knights of Spain, Warriors of the Sun.

“[That was] almost 50 years ago — and we still don’t have a good campsite,” DePratter said at the October dig. “That’s why we’re out here still looking, because Dennis is pretty sure that this is the area where Soto stopped.”

Before arriving on-site, the team didn’t know what to expect, DePratter said, “because nobody’s ever found a campsite. So, whatever we find here is informing not only us, but other people in other states who are looking for Soto campsites.”

With the team’s discovery of the pommel on Oct. 21, DePratter said, “We’ve found just what we came to find.”

Blanton has two main reasons why he’s sure he’s found a true Soto encampment: “There are more artifacts there than at any other place at Deer Run, and there’s more variety of Spanish artifacts, which fits the bill for a prolonged Spanish campsite,” he said.

“It’s only in the last four years, I would say, that we’ve gained this confidence that there’s no question that’s what we have. And the students have been there every step of the way.”

Identifying ‘doughnuts’

Returning to Deer Run, sometimes several times a year, Blanton and his students, colleagues and various volunteers have found hundreds of 16th-century Native American and Spanish artifacts.

“The very first year we went down there with a bunch of JMU students, we found a Spanish artifact, and it was a huge deal,” he said. “And I would say that lit a fire. It kept me going back. It kept students busy. But we lurched along. And that’s just the nature of archaeology. It really just has to be this sort of tenacious, relentless kind of searching.”

For a while, they weren’t sure exactly where to look. That all changed when Blanton realized the critical connection between Soto and the Native American villages built at Capachequi — a Native American territory that Soto’s expedition described in March 1540 and which Blanton has been studying.

“I had heard a rumor of some sites that have these peculiar features on the landscape,” Blanton said. “They look like giant, earthen bird nests. Sometimes I call them bagels or doughnuts, because that’s what they look like. I wanted to go map these things. They were on a plantation that’s near Deer Run, not on Deer Run, but I thought they were important.”

The features are former Capachequi houses that once looked like giant anthills but have since collapsed in the middle. “The ring is a vestige of a Native American dwelling,” Blanton said. “That’s the key point.”

After Blanton documented these extremely rare features at the nearby property, the land manager told him to look for them at Deer Run. “I said, ‘What are you talking about? I’ve been all over Deer Run. Haven’t seen these things before.’” But the manager had spotted these land oddities in his previous work as a timber cruiser, evaluating trees to calculate their timber value.

“He gave me an approximate location,” Blanton said. “I went back to it on one of my spring trips, one of these one-week deals. I was out there by myself, and I thrashed around in the woods with a machete ... and, lo and behold, I found ‘doughnuts.’ And I’ll tell you what, it was the most exciting thing. It was like walking into a Native American ghost town.”

Once he knew what to look for, Blanton was spotting them everywhere. He remembered how survivors of Soto’s expedition had written about the Capachequi houses looking different from the Native American houses they had encountered in Florida. “They were used to seeing all these Native American dwellings down there that were lightly built,” Blanton said. “They were like Florida verandas, you know, with thatch roofs and more open to the air.”

Instead, Soto’s men described the Capachequi houses like “caves under the ground,” Blanton said. “And that’s what we’re finding. These doughnuts are the surviving vestiges of the earth-covered Indian houses. ... And I was like, ‘Oh my gosh, this is what Soto talked about. These are the caves under the ground.’”

With that revelation, Blanton and his students returned for their 2019 summer field school with a new plan. They didn’t find Spanish artifacts, but they learned a lot about “doughnuts.” At their next field school in 2021, two students found a Spanish-made iron tool that Blanton first mistook for a piece of pottery. “It was right where the Indians left it inside one of these doughnuts,” Blanton said. “It was like, touchdown.” The discovery provided a compelling indication of Soto’s encounter with Capachequi’s native population.

The same year, another student working alongside Blanton’s colleagues with a metal detector found an iron tool that could be used as a hatchet or adze blade. Blanton called it one of “the rarest Spanish artifacts you could find." Made by the Spanish for trade with Native people, it is one of only two or three known from around the U.S.

“So now, honest to gosh, we had this equation. If you find a doughnut, you’re going to find Spanish artifacts,” Blanton said. “The majority of the Spanish artifacts we find are either in one of these earth-covered dwellings, or they’re in very close proximity to them.”

Learning the connection between the Capachequi dwellings and the Spanish artifacts makes sense, Blanton said. Soto had 600 hungry soldiers, and the Native American villages were the places most likely to have stores of food and, possibly, the precious materials that Soto was hoping to find.

Soto’s entrada was a quasi-military expedition, Blanton said. And the artifacts his team has been unearthing make that clear. Some of the main finds from his searches have been lead bullets, fragments of bladed weapons and an abundance of chains. The chains, especially, point to what Blanton called a grim aspect of American history.

“These would have essentially been the first slave chains in the New World,” he said. “When the Spanish came, they were very aggressive ... taking captives and taking over houses. It’s a very sobering kind of an artifact.”

Blanton’s latest visit also helped validate a hypothesis he made in 2015, when his students found artifacts that he guessed were left behind after soldiers commandeered a Capachequi residence. Ten years later, while retracing the site with a metal detector, Dr. Aaron Ellrich, an archaeologist with the Coastal Georgia Historical Society, unearthed the sword pommel precisely where that native residence was located. “What in the world is the real story behind that sword pommel?” Blanton wondered. “I mean, they were made to not come apart.”

Blanton hopes that through his research, he can reconstruct the story of Soto’s six days at Capachequi with archaeological evidence and at an unprecedented level of detail. He regards the Deer Run property as an unmatched laboratory for investigating such events.

“We have this contrast between the places where Indians were gifted these objects by the Spanish, and they took them back to their communities. And then we have this other place where the Spanish were planted for about a week, and they just littered it up with whatever they had,” Blanton said. “It’s really fascinating, and no one has ever had this opportunity to look at the full sweep of what one of these encounters in a discrete Native American territory looked like.”

In the JMU lab

Though not part of the excavation at Deer Run, JMU Anthropology students and lab assistants Anna Leo and Jonah Friedman have been thrilled for the chance to study Soto artifacts. In the JMU Archaeology Research Lab, they’ve been examining metal objects that Soto and his men might have fashioned from old barrel hoops for the purpose of trading with people at Capachequi.

“It’s not something that you find every day,” Leo said. “And even though these are small things, they lead to a bigger understanding of how people worked with these artifacts and how they saw something that was already there, and then they made something different. It’s really cool.”

For Leo, a second-year Cultural Anthropology major, the lab work is giving her a chance to learn more about archaeology, which isn’t required for her major. “This is just something that I’m also interested in,” she said. “A lot of people think that archaeology is all dig, but 90% of it is right here.”

Thinking she might pursue a career in museum curation, Leo likes working with artifacts and knowing she’s one of the first to see them up close.

Friedman, a third-year Anthropology major with a concentration in Archaeology, is enjoying this rare opportunity, and each day brings something new. “We’re the first people to do analysis on these,” he said. “Maybe I’ll be able to see something extraordinary.”

Many of Blanton’s students have been part of the Soto research through his summer field study, which provides an essential step for JMU Anthropology students to become fully fledged archaeologists. “It is a very important course for an archaeology student, because it is the critical credential for employment in the archaeological field,” he said. “The bachelor’s degree is not the critical piece. ... Your entry-level credential is completing that field-school course.”

At JMU, the archaeological field school is completed through ANTH 494: Field Techniques in Archaeology. But it isn’t the only way interested students can participate in Blanton’s research, and the work Leo and Friedman are doing is groundbreaking.

Other students have worked with Soto artifacts, but Leo and Friedman are the first to do a use-wear analysis normally applied to prehistoric stone tools, which Blanton has adopted for documenting metal artifacts. “It’s really a pioneering analysis that’s never been done,” he said.

He hopes to include Leo and Friedman at an upcoming professional conference and offer them professional publication credits when he starts writing up his artifact study. “These are some of the rarest artifacts,” he said, “not only in the country, but in the whole hemisphere.”

And yet, Blanton’s research is about more than artifacts. In conducting this research through the College of Arts and Letters and the Department of Sociology and Anthropology, Blanton said he and his students are pursuing “a sophisticated, groundbreaking example of archaeological research.”

“It’s fundamentally aimed at improving our understanding of modern world history, which began with Europe’s expansion into far-flung corners of the globe,” he explained. “The legacy of the associated events shaped the history that defines much about our world today. And because the ‘official’ written records about those events that we have inherited are often so vague, it is left to archaeology to fill out the story. All to say, it’s about far more than the evocative artifacts themselves and, in the end, about the humans who participated in those events.”

Defining the encampment

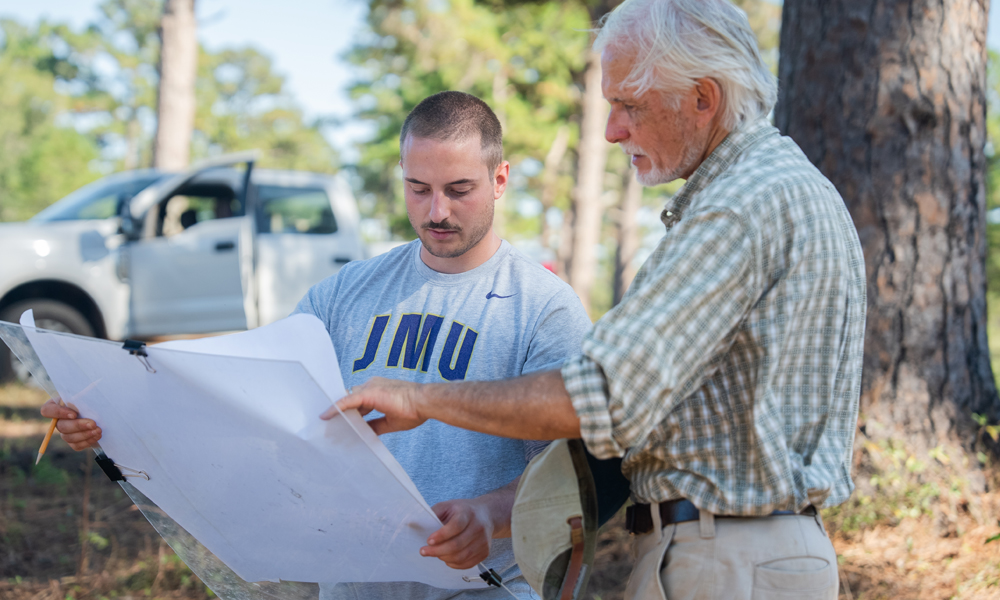

While at JMU, Kyle Mitchell (’24) took three classes with Blanton and also worked with artifacts in the archaeology lab. His field-school course was in North Carolina, and he participated in other field projects in Virginia. But he didn’t make it to the Deer Run site until after earning a Bachelor of Science in Anthropology and pivoting to a career in law enforcement. Having stayed in touch with Blanton, Mitchell eagerly accepted an invitation to join Blanton’s team of experts on their fact-finding mission.

“We’re finding a lot of cool stuff out here, and this is the first site I’ve been on that they’ve done systematic metal detecting like they are down here,” Mitchell said. “I’ve been mapping all of the grid points and all of the finds that they’ve had — so all these shovel tests, all the metal-detecting finds they’ve had, I’ve been mapping all of that. I’m helping Dr. Blanton do the documentation portion.”

Now a police officer in North Carolina, Mitchell said he still enjoys archaeology and didn’t want to abandon that passion. “I wanted to stick with it and get to be out on sites like this, and help him document and learn everything we can. ... They’ve found a lot over the years, but we’re really just starting to learn more and more about the Spanish encampment that was out here.”

Asked about future opportunities, Mitchell said, “Whenever Dr. Blanton needs me down here, I’ll be here.”

Joining him were several independent consultants, longtime volunteers, and Blanton's colleagues from the University of South Carolina, armed with notebooks, metal detectors, GPS devices, ground-penetrating radar, and a magnetometer to help uncover artifacts of a Soto encampment, define the lay of the land, and map the site.

“The footprint would be considerable,” Blanton said. “We’re trying to understand, really, for the first time, what one of these things would actually look like. Sort of theoretically we know, but in reality, we don’t. When our surveying begins to find nothing, that tells us where the encampment is not.”

Chet Walker and Aundrea Thompson, archaeological geophysicists from Archaeo-Geophysical Associates based in Austin, Texas, were conducting magnetometer and ground-penetrating radar surveys. “The archaeology kind of tells you the date of things,” Walker said, “... and geophysics allows you to see bigger patterns across the landscape.”

While in the field, their work mainly involves walking back and forth to collect data before taking it back to their lab. The ground-penetrating radar is a cart with a transmitter and receiver, which transmits and receives a signal to record on a computer. The fluxgate gradiometer is more of a passive instrument that records ambient magnetic fields to map the subsurface of the land. Eventually, the data can be uploaded to a geographic information system, so future researchers will know where to access the Soto encampment or how to apply it to a greater understanding of Soto’s path.

“What we’ve done this trip we’ll find out in a couple of weeks when we’re processing the data and writing the reports for Dennis,” Walker said. “It’s a great honor to be involved with a project like this. Regardless of whether or not it turns out to be a big find, the process of doing archaeology is kind of the same — what drives me, personally. The big finds are great, but it’s more the process of looking that I enjoy.”

Following in the footsteps of history

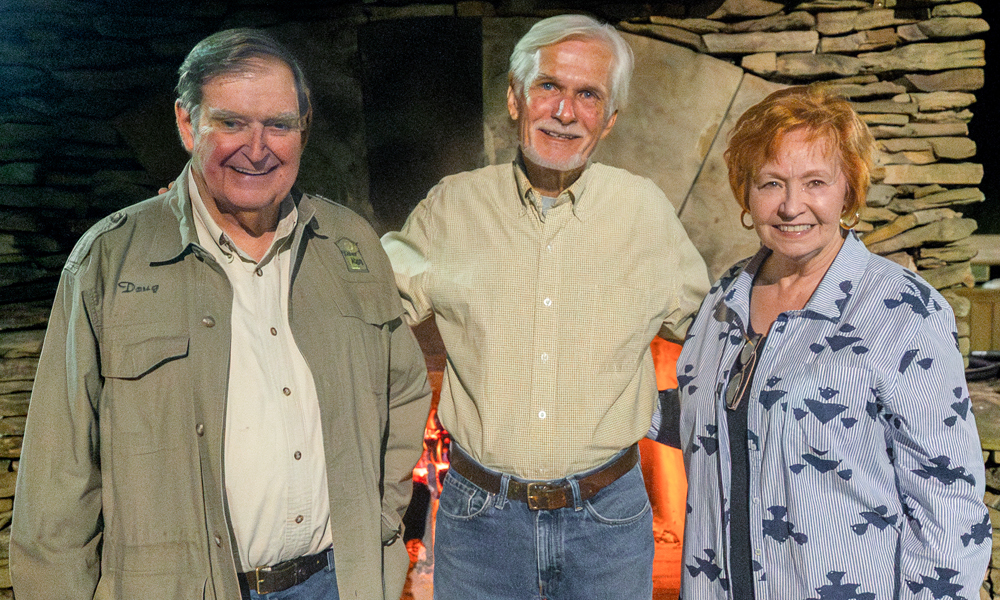

Blanton’s latest visit to Deer Run with several of today’s leading Soto experts was one of a few major next steps in his research after facilitating an archaeological salon, which he and Ivester hosted and Fernbank Museum co-hosted at the plantation in March 2024.

There, Blanton, DePratter and several other archaeologists trying to pin down the sites of various 16th-century Spanish entradas across the American interior, compared notes before journeying on horseback along the path that Blanton believes Soto might have taken across the Deer Run property to where about 24 earthen doughnuts marked the location of a suspected Capachequi village.

Blanton recalled the moment Dr. John Worth, an anthropologist with the University of West Florida, turned to him in awe at witnessing the site he had only read about and imagined. “He looked at me and said, ‘This is it,’ and I about fell off my horse,” Blanton said.

Though his peers are not always easily persuaded, Blanton said the revelations from the salon marked a pivotal moment in the search for Soto and other Spanish colonialists. Unlike many other archaeological finds, this one hasn’t been contested by those who have seen it up close. “There’s 100% consensus, which is unheard of,” Blanton said. “There is 100% consensus that we are dealing with Soto.”

The site at Deer Run is also the first confirmed location in North America where researchers believe Soto set up camp, besides his long-believed winter encampment in Tallahassee, Florida.

A major outcome of the 2024 salon was the formation of the Colonial Encounters Research Consortium, which met formally under the CERCa name at Fernbank Museum in the spring of 2025 and plans to meet yearly to discuss developments in its members' mutual search for Spanish artifacts in the U.S. In May, CERCa will meet again at Deer Run.

Over the years, Fernbank has supported Blanton’s archaeological fieldwork as well as laboratory work, artifact analysis and artifact conservation, a museum statement explains. As part of the museum’s educational programming, they have presented exhibitions and lectures on the Spanish contact period, fulfilling its ongoing mission “to ignite a passion for science, nature, and human culture through exploration and discovery,” the statement explains.

“We are honored to be a part of the search for the elusive Hernando de Soto and the groundbreaking archaeological research that is truly rewriting history of the early Spanish period in this region,” says Jennifer Grant Warner, president and CEO at Fernbank. “While defining Soto’s route is certainly important, perhaps the real significance of this research is that it will continue to inform discussions around early Native communities and the impact of Spanish contact that can be viewed on a more global scale. As a museum of natural history, we believe these stories are important to highlight.”

One big reason Blanton and his colleagues have been able to find so much at the Deer Run site is because the land has been largely untouched by development.

After retiring from Coca-Cola in 2000, Ivester grew Deer Run Plantation from four separate farms he purchased over the next 13 years. His initial goal was to have a place for quail hunting. He quickly became invested in the property’s already thriving pecan business. But it wasn’t long before he learned of his vast collection of Native American arrowheads.

Having lived and worked in Atlanta for more than 20 years, he was a previous board member of the Fernbank Museum and knew who to call to find out if the arrowheads were important.

“I grew up in the brand business,” Ivester said. “My belief is that when you have a brand, you either polish it every day or you diminish it every day. There’s no standing still. You’re either improving it or you’re taking away from it a little bit.”

Viewing himself and his wife, Kay, as temporary stewards of the land, he’s thrilled to provide a legacy for his 25,000 acres and the two dozen people who work and live there, many with their families.

“For us, it’s a real package deal,” Ivester said. “It’s about the land, it’s about the people, it’s about the reputation, and in the end it’s about the brand. We’re fortunate in this legacy or heritage that is here because of what Dennis Blanton has found.”

Blanton, who plans to retire from JMU in the spring, will continue his Soto research for the foreseeable future, recording and analyzing artifacts, and continuing periodic field studies. Over the years, the successful partnership of Blanton as the academic expert; Ivester and his wife as project supporters and hosts; and Fernbank as the lead sponsor has enabled the work to continue and Blanton’s team to keep making landmark discoveries.

Calling Blanton a great friend and a mentor in terms of his anthropological expertise, Ivester is in it for the long haul. “When we started, I didn’t know where it would lead,” Ivester said. “I thought the journey was more important than the destination, and, at this point, I still don’t feel like we have achieved a destination. We’re still on the journey.”