Gray's Analyses: Decoding Data Using Constructed Cartography

NewsBy Dan Armstrong, JMU Public Affairs

On a standard map, Afghanistan and Iran share a border. But from the perspective of a team of James Madison University researchers, the two countries are a world apart.

That's because the team — Dr. Lincoln Gray (communication sciences and disorders), Dr. David Bernstein (computer science) and Jennifer McCabe (JMU libraries) — develops "constructed charts" based not on the physical proximity of locations to each other, but rather their relationship to common data points—in this case, rates of successful vaccination against diphtheria.

Using constructed cartography, the team has helped researchers across several fields discern clear, understandable patterns from vast amounts of complex data.

"Part of my job as a scientist is to find patterns in nature," Gray said. "We have a simple model that successfully describes complex patterns."

The method combines multidimensional scaling, a data reduction strategy that clusters problems and solutions in terms of their relationships to each other, with the concept of functional distance to visually depict patterns in data.

Functional Distance

The analyses depict how "close" or "far apart" things are based not on geographic distance, but rather using "functional distances" based on relationships those objects share.

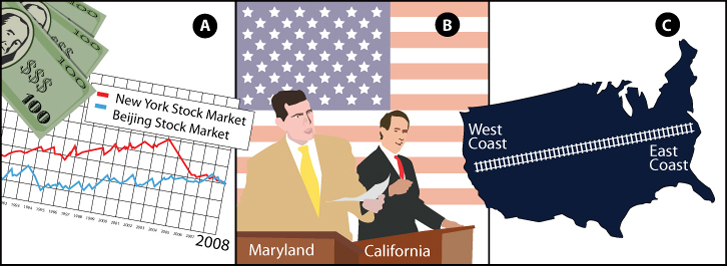

For example, the East Coast and West Coast of the United States have always been thousands of miles apart. But when the transcontinental railroad was completed, the time it took to travel from one coast to the other was drastically reduced. Thus, the functional distance between the East and West shortened.

In another instance, the New York City and Beijing stock exchanges are physically located on opposite ends of the globe. But since the two markets share similar trends in stock prices, they are functionally close.

Recently, the team used constructed cartography to depict immunization efforts against several common diseases in 49 developing countries.

"I was interested because in all my previous work, I'd looked at how diseases spread," Gray said. "This is a way of looking at how our attempts to fight disease spread."

The vaccination research, currently in press in Health Informatics Journal, draws on seven sets of data – immunization rates for six diseases and a tracking of government expenditures for vaccinations – for 49 countries.

Such a massive amount of data potentially offers a great amount of insight into current immunization efforts, but in its raw form, the complexity and interrelation of the data and the obscuring effects of random variation pose great challenges to those trying to unlock its patterns.

But after the data is charted in one, two, three or even four dimensions using calculated functional distances, the picture is clear. With the added tool of interactive digital renderings, people can physically watch patterns spread across a digital map simply by dragging a mouse.

"It's a mathematical concept, a graphic analysis to place complex data in a map," Gray said. "Information is neither created nor destroyed in this practice. It merely extracts the fundamental underlying patterns that already exist in the data."

Since Iran's diphtheria immunization efforts have been very successful – 99 percent of the nation's 1 year olds have been vaccinated – and Afghanistan's have not (just 47 percent vaccinated), they appear far apart on the constructed chart.

The results are valuable to epidemiologists, governments and international aid organizations in that they reveal clear patterns in immunization success that can then be checked against specific variables in each country to determine the issues that lead to disparity.

In other words, the constructed charts reveal how successful immunization efforts spread so that others may determine why they spread the way they do.

Money Isn't the Root

The team was able not only to decipher patterns in successful immunization rates among countries, but also compare them with patterns how much countries spent on their efforts.

The results were surprising.

"A fundamental interesting result is that the way the immunizations spread was of a very different pattern from the way the money was spent," Gray said. "Now we've got to figure out why the mapping of the money doesn't follow the pattern of successful immunizations."

Since the results have shown that high government expenditure is not a good predictor of successful immunization, the next step is for social scientists to look for cultural, economic, political or other issues that are leading to the disconnect.

"It would seem, whenever you get a mis-mapping like that, it would say there's something happening that needs to be investigated," Gray said.

Other Applications

One of Gray's early jobs after finishing his Ph.D. in zoology and neuroscience at Michigan State University was working as director of research at the University of Texas Medical School Department of Otolaryngology, Head and Neck Surgery.

There, Gray saw another opportunity to apply his technique.

"I was working in an otolaryngology department and my colleagues were head and neck cancer surgeons, and I got interested in their problem, which was, 'what are the patterns of how this disease spreads?'" Gray said.

The result was an interactive diagram of the head and neck, where a patient, doctor or researcher can select the site of the primary metastasis and watch where the cancer is most likely to spread over time. The chart showed that the cancer spread from location to location not based on their physical proximity, but on some other pattern.

"The map is showing what surgeons already know – that the cancer doesn't spread to the next closest place. We believed it spread in a non-random pattern, but not just to the next closest place," Gray said. "This chart essentially shows the tumor's view of the body."

Since joining the JMU Communication Sciences and Disorders faculty, Gray said the emphasis on collaboration among his department, college and the university as a whole has led to applications of constructed cartography he couldn't have imagined on his own.

His work mapping human migration patterns was presented with Vice Provost John Noftsinger and Ken Newbold and Ben Delp of the Institute for Information and Infrastructure Assurance at the Forum on Public Policy last year, and his work on cancer mapping has been published in several medical and scientific journals.

"The Constructed Cartography project was a good idea by a remarkable dean, [now vice provost] Jerry Benson. It's me and a librarian and a remarkable Java programmer. Where else could this have gotten done? I don't know," Gray said.

While at JMU, Gray has produced constructed charts modeling patterns in data sets ranging from the spread of cancer within the body to the proliferation of West Nile virus in Virginia to patterns of human migration among different countries.

"The administration has really tried to build a place where we're not all just in our individual silos, looking up and looking down. We get to look sideways a little bit," Gray said.

Mapping a Course for the Future

Gray continues to seek more sources of medical data for use in new projects. Most of the data he's used has come from major hospitals, but privacy issues and a lack of large, meaningful data sets make such sources rare.

In the meantime, Gray said possible collaborations in the fields of medicine, anthropology and economics are on his radar, as well as trying to connect with scientists from other fields to implement further study into global issues using the patterns he's outlined.

"The exciting result is that using this technique of constructed cartography, we can extract underlying patterns in both how diseases spread and how we try to fight those diseases," Gray said. "The next step is to overlay those two maps and see where they are congruent, to see where what we're doing is effective."