Taking a Closer Look at “the Pharmacy of the World”

M.A. in Political Science, European Union Policy Studies

By Lily Gates

It has been a long year of combatting Covid-19 in Europe, where multiple lockdowns and shuttered borders curbed death tolls but ravaged the union’s economy. Hope now lies in vaccines. However, getting Europeans vaccinated has not been a walk in the park. Initially, the European Union chose to act as a single bloc and advanced slowly compared to the United States and the United Kingdom. The state of vaccinations in Europe has since improved significantly. However, the experience of the past 6 months does pose some questions: What exactly happened in the EU? Were the delays a reflection on the EU’s choice to act collectively? And most significantly, what will the EU’s unified approach to vaccine rollout mean for European citizens and the future of EU political integration?

Health policy in Europe is presently a member state competence. However, back in June 2020, the 27 member states gave the European Union sovereignty over managing the Covid-19 vaccine rollout process. In simple terms, the EU is trusted with purchasing and distributing vaccines to member states. The current rollout protocol prescribes vaccines to each member state based on their population size. If a member state rejects the vaccines, their portion will be redistributed to the rest of the union. This unified European approach is echoed in the Covid-19 financial recovery package NextGen EU, worth €750 billion, and continues the trend of increased European political integration in response to crises.

It’s important to note that acting as a single bloc does not eliminate member-state freedom or leave EU officials to act unchecked. Member states are still responsible for managing the distribution of jabs to their citizens. They can also purchase doses from vaccine suppliers not currently in contract with the EU if they wish, such as the Sputnik vaccine from Russia. This gives member states freedom to seek other solutions if they do not approve of the cost or health standards of vaccines distributed by the EU.

The European Union’s approach to vaccines was motivated by internal equity. Malta’s health minister noted that, “the alternative of not having procured vaccines together would be that we would be competing between European member states,” with the risk of some member states falling behind. In the context of Europe’s incredibly integrated single market, an unequal vaccination rate could have further damaged an already suffering economy.

The European Union’s approach to vaccines was also motivated by equity beyond its borders. In her opening address for the recent State of the Union conference held in Florence, European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen proudly stated that Europe had used multilateral channels such as the World Health Organization’s COVAX initiative to export medical supplies and over 200 million vaccines. This number closely matches the amount of vaccines distributed to EU member states themselves. By sharing vaccines globally, the EU sought to mitigate the risk of new covid strains that could send the entire world into another cycle of lockdowns.

So, where did the European Union go wrong? The EU’s single bloc strategy was effective and equitable on paper but did not translate smoothly into reality. Here are a few factors that may have contributed to the ineffective implementation:

- Struggles with AstraZeneca: The most obvious contributor to a slow vaccine rollout was the failure of AstraZeneca, the EU’s primary contracted supplier, to deliver two-thirds of its promised 90 million doses in the first three months of 2021, with little hope of improvement by the contract’s end in June. The EU will not be renewing its partnership with AstraZeneca, and instead recently signed a contract with Pfizer-BioNTech to receive 1.8 billion doses over the next three years to cover vaccinations and booster shots.

- Export and Import Imbalance: European policymakers did not anticipate becoming the “pharmacy of the world.” While the EU maintained open international trade, other vaccine producers like the US imported doses without exporting in return. This deficit left few vaccines for Europeans themselves. The EU also did not anticipate having less access to vaccine production goods from certain global partners. The chief production officer of CureVac (a German company looking to produce their own vaccine) noted that the Defense Production Act requires US suppliers to prioritize domestic market needs, making it difficult for European biopharmaceutical companies to continue importing goods such as “chemicals, equipment, filters or hoses” from the US. In response to these trade imbalances, the EU is considering restricting vaccine exports going to countries with already-high inoculation rates, as well as countries refusing to export their own vaccines and medical supplies.

- Inexperience: Underlying these external factors is the fact that the EU simply has less experience in managing global health crises than its major transatlantic partners. The UK and US were faster than the EU in approving vaccines. The EU may also have used gentler language than the US and UK in its contract with AstraZeneca. Lastly, in contrast with the US’s Operation Warp Speed program funding facility development, the EU let manufactures figure out how to meet quotas on their own.

There are some obvious external factors that did not help the European Union’s vaccine rollout – namely AstraZeneca’s failure to supply and the EU’s high rate of international vaccine exports that deviated from the US and UK’s more nationalist approach to vaccinations. There were also glaring mistakes that the EU made internally with its management of the vaccine rollout due to inexperience. Regardless of causality, the price of this failure-to-launch was more infections, higher death rates, and continued economic lockdowns that could have been avoided.

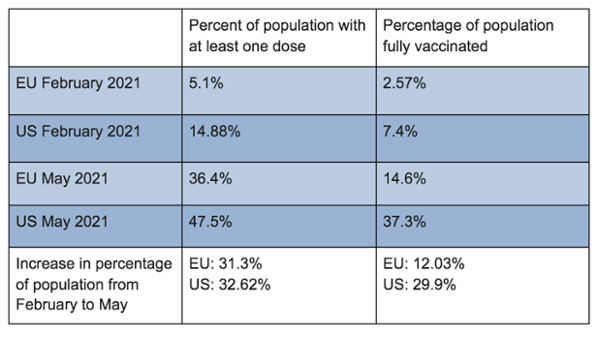

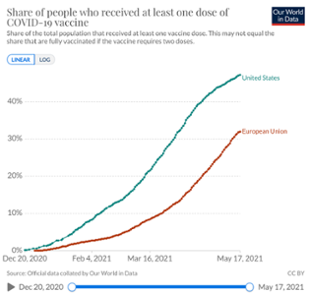

Thankfully, numbers do show that the EU is finally catching up to its transatlantic partners. Adjusted for population size, the EU was about seven weeks behind the United States as of early May.

Center for Disease Control and Prevention. 2021. “Covid Data Tracker.” Accessed at https://covid.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker/#vaccinations on 5/18/21. </em

Our World in Data, Oxford Martin School. Accessed at https://ourworldindata.org/covid-vaccinations?country=ITA on 5/18/21.

The EU has been working hard to right wrongs, with a new contract with BioNTech-Pfizer, stricter vaccine export restrictions, and a goal similar to the US of reaching 70% of its population vaccinated by July. Surprisingly, these new adaptations to the vaccine rollout showcase a shift away from the characteristically European multilateral foreign policy strategy. Onlookers are particularly critical of the long-term contract with BioNTech-Pfizer and how it could potentially take vaccines away from other countries in greater need of doses. While the EU does have a clause in their contract allowing them to sell/donate any leftover doses, the faint eau de toilette of a Europe-first attitude is surprising and may have been spurred on by other nations taking a nationalist approach to vaccinations.

Nonetheless, Ursula von der Leyen made it very clear in her recent opener to the State of the Union conference that the EU will continue to promote global vaccinations in order to mitigate the development of new strains of the virus, while also improving the vaccination process within EU borders. If the EU is able to reach its vaccination target goals in July, then this could be considered a success for the single bloc approach to vaccine rollout despite setbacks at the beginning of 2021. Only time will tell about the effectiveness of the European Union in addressing Covid-19, but the daily exponential growth in European vaccinations is a promising sign.

In the spirit of the EU’s values of equity and multilateralism, it is fitting to end with this quote from von der Leyen addressing the criticisms of the EU: “Some might say, ‘well, countries like the US and the UK have been faster [with vaccine rollout] at the beginning.’ But I say, ‘Europe achieved this success while remaining open to the world.’” And, for better or for worse, open to the world they will remain.

Lily Gates is a current student in the Class of 2021 EUPS program. She graduated from James Madison University in 2020 with a double major in public policy and philosophy. After graduation, she will be working as a fellow with the U.S. Department of State in international security and recovery operations.