Surveying Eighty-Year-Old Battlefields in Solomon Islands

CISR JournalThis article is brought to you by the Center for International Stabilization and Recovery (CISR) from issue 28.1 of The Journal of Conventional Weapons Destruction available on the JMU Scholarly Commons and Issuu.com.

By Simon Conway [ The HALO Trust ]

Surveying battlefield sites and abandoned ammunition depots eighty years after a conflict presents a challenge. There are few living witnesses, and the land has often changed beyond recognition. In Solomon Islands, the situation is exacerbated by a combination of familiarity and lack of information. Civilians have grown accustomed to the presence of ordnance and concluded that the problem is intractable. At the same time, it is not known how many people have died or been injured because of unexploded ordnance (UXO) and abandoned (AXO) ordnance. Nor is it known where the accidents occurred or what the victims were doing at the time of the accident. This lack of accident data has made it difficult for Solomon Islands to draw attention to the scale of the problem and request help through the assistance clauses of treaties including the Convention on Certain Conventional Weapons and the Anti-Personnel Mine Ban Convention. It makes it nearly impossible to write a national casualty reduction strategy built on solid data.

Solomon Islands is an extended archipelago northeast of Australia and east of Papua New Guinea. It is a strategically important location because whoever controls the airfields and the deep-water ports spread across the nation’s 1,500 kilometer frontage, controls access to the South Pacific, potentially cutting off the United States from its allies in Australia and New Zealand. That is what the Japanese intended when they captured the islands in the aftermath of the attack on Pearl Harbor and it is why the United States and its allies fought so hard to recapture them.

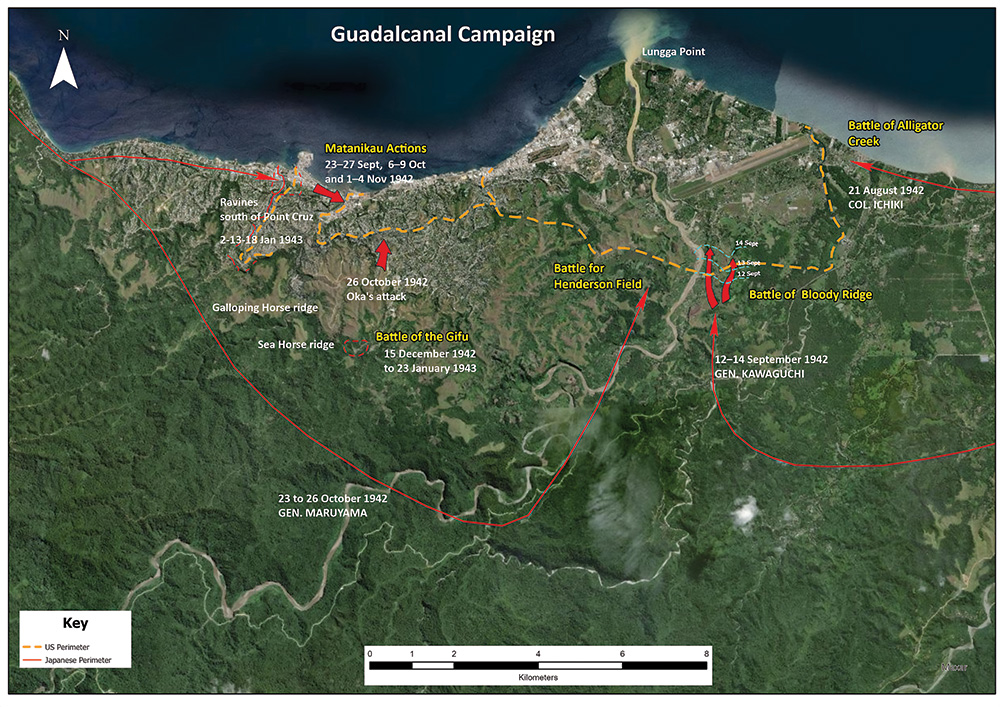

The land battles on Solomon Islands were savage, involving heavy naval, air, and artillery bombardment, and close quarter fighting with mortars and grenades. In addition, storage depots were built to enable combatants to move ammunition closer to the shifting front lines. In many cases, these depots were abandoned or blew up due to the difficulty of keeping them safe and secure. The result has been a legacy of UXO and AXO contamination that exists to this day.

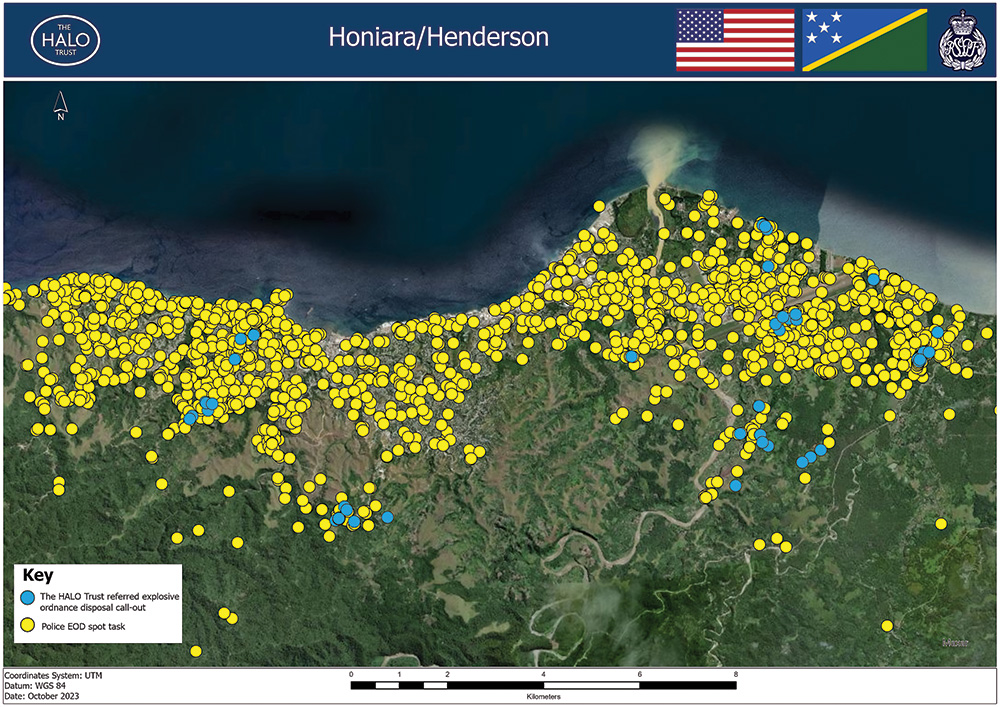

Until recently, the focus of international assistance has been on providing support to the Royal Solomon Islands Police Force (RSIPF). The RSIPF, as the sole organization authorized for the disposal of explosive ordnance (EO) nationally, has a highly effective explosive ordnance disposal (EOD) unit, which has successfully destroyed 48,000 items of EO since recording keeping began in 2011.1 A review of the information for the period 2011 to 2020 by The HALO Trust (HALO) revealed that 80 percent of the EO destroyed was US manufactured, 17 percent Japanese, and the remaining 3 percent British, German, and French.2

The actions of the EOD unit have undoubtedly saved many lives, but callouts are essentially reactive and rely on the public to continue reporting the discovery of UXO. Reporting tends to peak in the immediate aftermath of a UXO-related fatality but drops again within months. UXO may also be viewed as a financial resource, with people choosing to harvest the explosives and sell them rather than reporting their location to the police (i.e., fish-bombers buy and use the explosives to stun and kill fish, destroying the once pristine ecosystem of the reefs). In remote areas, the distance between communities and police stations means that there is a significant, chronic issue of underreporting. The EOD unit does not currently have sufficient staff to conduct technical survey or sub-surface clearance.

There is a huge task under the ground waiting to be addressed. One of the few places where sub-surface clearance has happened is the stadium built near the center of the capital, Honiara, for the seventeenth Pacific Games held in November 2023. A local company staffed by former RSIPF personnel searched the site, which was about 60,000 square meters, and excavated more than 8,000 items up to 4 meters deep, ranging from canon rounds to artillery shells.

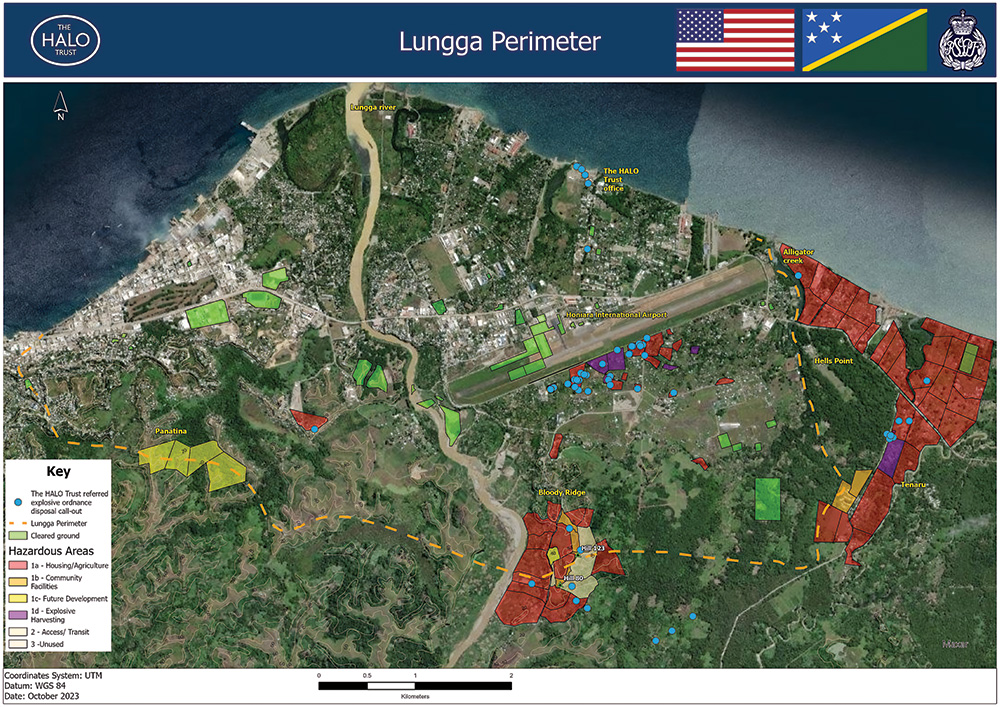

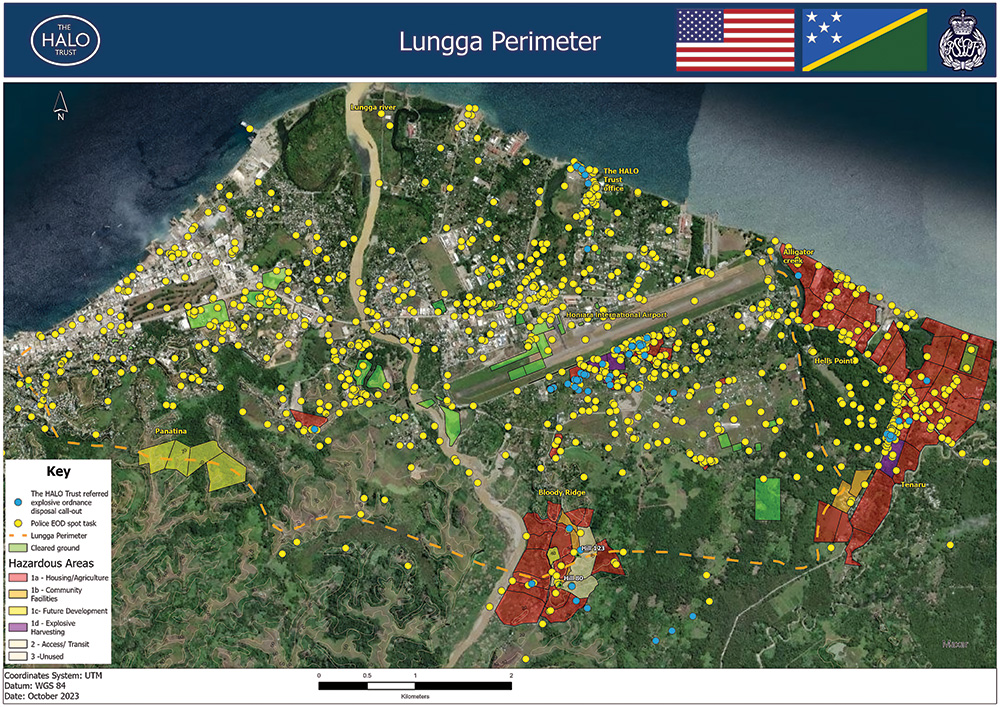

HALO was awarded a contract by the Office of Weapons Removal and Abatement in the US State Department’s Bureau of Political/Military Affairs (PM/WRA) to undertake non-technical survey (NTS) of contamination in Solomon Islands. Given the scale and intensity of the bombardment, it would be tempting to draw a series of large circles around the ports and airfields, which are also now the most densely populated areas, and declare everything inside that range a hazardous area. However, HALO is identifying and carefully delineating the boundaries of those distinct areas that are the most contaminated and would yield the most benefit from sub-surface clearance. In doing so, we hope to galvanize international support around a narrative of making the islands a much safer place.

While there may be a paucity of data about the consequences of the fighting—particularly the post-conflict impact on civilians—there is plentiful and granular data about the battles themselves. Sources range from US Air Force Theatre Historic Operations Records to the ongoing research conducted by professional and amateur historians, including Dave Holland who runs a Facebook site called Guadalcanal—Walking the Battlefield. Entering the name of the battles in a search engine yields a range of maps that not only show the location of ports and airfields, as well as the movement of military units, but often provide accurate information on the location of trenches, dug outs and bunkers, and even artillery targets.

Local relic hunters make a living from scouring the jungle, selling a range of salvaged items from bayonets to belt buckles, and dog tags to coke bottles. They are valuable sources of information about the location of buried caches of ordnance.

HALO’s approach has been to use battlefield information and the RSIPF clearance records to guide where we initially deploy the five-person survey team. From there, we used a participatory approach, writing to community elders to introduce our work and organizing open meetings at which men and women have been encouraged to share information on the location of “bombs” and to provide contact details. Not long after our arrival in Mbokona, a largely informal settlement known as “the ravine,” a nine-year-old walked up to the HALO survey team and handed over a Japanese Type 91 grenade that was fired from the end of a rifle more than seventy years before he was born. The incident reinforced the need for greater public awareness of the risk. From the beginning of HALO’s operations, we have delivered explosive ordnance risk education (EORE) as a component of those meetings and as a follow-on activity. In December 2023, we started distributing leaflets, posters, and school exercise books with an EORE message with funding from the German government. All EORE materials include the dos and don’ts stipulated by the police, including “don’t build fires”—such is the density of contamination and the threat it poses.

For survey, HALO decided to save time by dispensing with hand-drawn sketch maps of hazardous areas, instead opting to digitize field data collection and mapping using handheld tablets with Esri ArcGIS Survey123 software and DA2 GNSS receivers with an accuracy of up to 30 centimeters. Being able to collect and assess historical data and map offline has allowed HALO to work unimpeded in areas without mobile data coverage. Using the Trimble receivers—which are easy to set up and use, even in challenging terrain—has significantly sped up survey.

During field activities, four separate reports are completed: Community Assessment, NTS Hazardous Area, EORE, and EOD call-out. Every report undergoes three levels of thorough quality control checks to ensure the data is fit for purpose. The reports are entirely Information Management System for Mine Action (IMSMA) compatible and will be digitally ported into the national database when it is functional in 2024.

When delineating the boundaries of hazardous areas in regions that were the target of industrial-scale bombardment, HALO’s emphasis has been on manageability. We consulted the police and the commercial clearance sector and decided on a maximum size of 60,000 square meters for each polygon, reflecting the size of land the local commercial clearance companies can clear on average in a two-month period. For the larger battlefield sites, we have created multiple adjoining polygons, each one a distinct task. From June to December 2023, HALO surveyed 206 hazardous areas, covering a combined area of 8,281,979 square meters, averaging just over 40,000 square meters per polygon.

To assist the government with understanding the scope of the problem and to differentiate its impact, we also developed a color-coded system that indicates the current or proposed land use for the hazardous areas. Red areas represent housing and cultivation. Orange areas denote community facilities such as schools, community centers, churches, and the national park area at Bloody Ridge. Yellow areas are earmarked for future development, such as the affordable housing proposed by the National Provident Fund. Areas where explosive harvesting has occurred are marked in purple. Finally, gray areas are not currently in use. Of course, this is just a snapshot as of the date of the survey, but HALO will update the coding as the land use changes.

Inevitably, HALO found items of UXO and AXO during the survey: 731 items between the period of June to December 2023. On Guadalcanal Island, these were reported to the police EOD unit who responded swiftly in every instance. While surveying the battle of Munda Point on New Georgia Islands in the Western Province, HALO was fortunate to have a police EOD officer accompany our team who removed safe-to-move items to a secure location. The close cooperation with the police and their swift response has undoubtedly given communities renewed confidence in reporting the presence of EO and is beginning to break down the sense of the problem as an intractable one.

From the outset, HALO sought to apply the principles of good information management, with a strong emphasis on audit and continuous appraisal. We have been working with the Geneva International Centre for Humanitarian Demining (GICHD) and Solomon Islands government to prepare for the monthly digital transfer of good-quality data to the new National IMSMA Core database.

It is important to recognize that the UXO problem in Solomon Islands is never going to be completely solved. Just as in Western Europe, clearance of World War II ordnance will continue for years to come, but it is also important to acknowledge that people in Western Europe are not dying because of building bonfires or having barbecues. In Solomon Islands, more can be done. The survey is a significant step toward measuring the scale of the problem and identifying the resources required to address it.

See endnotes below.

Simon Conway starts up new programs for The HALO Trust. He has worked in the mine action sector since 1998.

Simon Conway starts up new programs for The HALO Trust. He has worked in the mine action sector since 1998.