The Mine Action Trauma Care Collaborative

Enhancing Coordination between Humanitarian Mine Action and the Emergency Health Response to Civilian Casualties of Explosive Ordnance

CISR JournalThis article is brought to you by the Center for International Stabilization and Recovery (CISR) from issue 28.1 of The Journal of Conventional Weapons Destruction available on the JMU Scholarly Commons and Issuu.com.

By Hannah Wild, Christelle Loupforest, Loren Persi, Elke Hottentot, Sebastian Kasack, Firoz Alizada, International Blast Injury Research Network, Adam L. Kushner, Barclay T. Stewart, PhD

Modern armed conflict is characterized by the use of a wide variety of explosive weapons (EW), creating complex injury patterns with the need for rapid first aid including hemorrhage control close to the point of injury. Yet, in many places where these injuries occur, formal trauma systems are weakened by conflict and resource limitations. In conflict zones, where immediate trauma care is often challenging to access for civilian casualties of EW, the humanitarian mine action (HMA) sector’s unique position and capabilities present a critical opportunity to bridge this gap—a potential that has been realized with the creation of the Mine Action Trauma Care Collaborative (MA-TCC). By fostering collaboration between the mine action sector and health responders, the MA-TCC aims to leverage HMA’s extensive field presence and expertise to enhance trauma care delivery, ensuring a more coordinated, effective response to the urgent medical needs of those injured by EW.

Background

Twenty-first century armed conflict is characterized by the use of explosive ordnance (EO), such as landmines and improvised explosive devices (IEDs), as well as ground-launched and air-dropped EW with wide area effects including cluster munitions and barrel bombs that disproportionately impact civilian populations.1,2,3 In particular, the threat posed by IEDs has grown, accounting for nearly half of the 9,198 casualties recorded by UN programs in 2022 (46 percent from 38 percent in 2021.)4 The blast mechanisms and penetrating fragmentation effects of such weapons create complex, multidimensional injury patterns with the need for rapid first aid close to the point of injury (e.g., hemorrhage control).5 Yet, in many places where these injuries occur, formal trauma systems are weakened by conflict and resource limitations. Epidemiologic analyses of civilian casualties of EO estimate a 39 percent case fatality rate, approximately five times higher than that observed in military treatment facilities or civilian trauma centers in high-income countries.6,7

While responsibility for the provision of medical care to civilian casualties during active conflict lies with parties to the conflict under international humanitarian law, this burden often falls to local and multilateral health authorities, as well as nongovernmental organizations (NGOs). HMA stakeholders have an organized presence in many hard-to-access settings where local health infrastructure is disrupted by conflict and frequently located far from points of injury. Such resources and capabilities include extensive networks in conflict-affected communities through explosive ordnance risk education (EORE) activities; victim assistance efforts; and the medical expertise of demining teams, with each individual trained to the level of “basic medic” and at least one paramedic per team to treat deminers in case of illness or accidents. HMA personnel may be the best-equipped medical resource in their area of operation. As such, HMA stakeholders have significant potential to strengthen emergency care in settings with fragile health infrastructure. This can be achieved by supporting local capacity-building through training layperson first responders (LFR), strengthening of referral pathways and prehospital notification systems, and reciprocal “refresher” trainings for HMA paramedics in local health care facilities where trauma team resuscitation drills could be conducted to improve casualty care. Further, the HMA sector sets precedent for high-quality information management standards and platforms for systematic data collection in challenging operational environments. This system creates an opportunity to establish minimum standards for data collection in the context of emergency health care which will lead to the development of benchmarks for effective intervention for the most at-risk populations.

Yet to date, potential for collaboration between HMA stakeholders and emergency care capacity-building for civilian EO casualties has not been explored in a structured manner. While there are multi-mandated organizations engaged in land release and EORE, as well as a continuum of victim assistance services, overarching coordination between HMA and local health systems could be significantly strengthened to enhance the emergency response to civilian EO casualties.

Numerous recent policy frameworks and sector standards provide momentum to improve coordination between HMA and stakeholders in the emergency health response to civilian casualties of EO, including the recently published Joint Operational Framework on Health and Protection, the implementation of the Oslo Action Plan containing provisions on emergency medical services (Action 36), and the recently adopted International Mine Action Standard (IMAS) 13.10 on Victim Assistance in Mine Action.8,9,10 Within the health sector, aligned priorities are put forward by the World Health Organization (WHO) Emergency, Critical, and Operative care (ECO) resolution recently adopted at this year’s World Health Assembly (ECO Resolution/76.2), as well as the development of the WHO Red Book, a consensus guideline on the coordination of clinical response teams in armed conflict.11,12 These initiatives coincide to present an ideal opportunity to strengthen cross-sector partnership. MA-TCC was created to serve this purpose. The Collaborative is a multidisciplinary initiative with the objective to realize increased HMA contribution to strengthening trauma care by creating pathways for partnership between the HMA sector and the emergency health response in conflict and post-conflict settings.13

Preliminary Studies and Partnership-Building

The MA-TCC began as an exploratory dialogue between researchers at the University of Washington (UW) and the United Nations Mine Action Service (UNMAS) to define high-value opportunities for enhanced engagement between HMA and emergency health response stakeholders. We undertook preliminary studies to: 1) identify evidence-based trauma care interventions that reduce injury-related mortality in low-resource and conflict-affected settings; 2) evaluate barriers and facilitators to implementation; 3) model the cumulative mortality reduction potential of these interventions; and 4) establish an integrated chain of post-blast care from point of injury to definitive treatment at a health facility with explicit opportunities for engagement by mine action stakeholders.

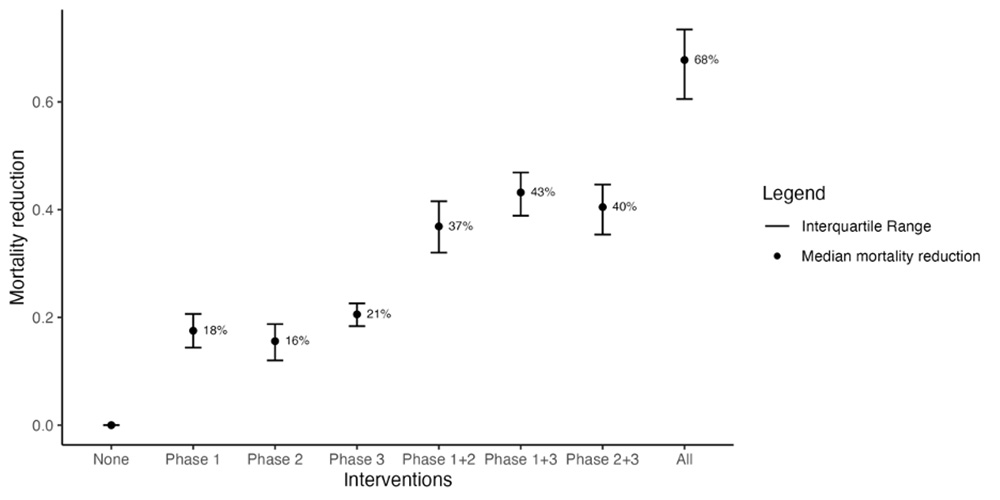

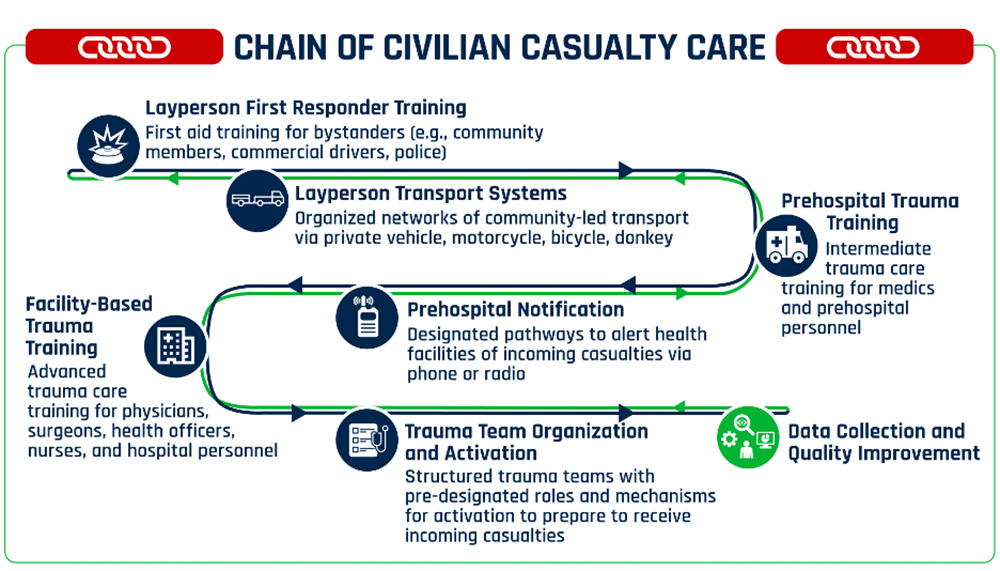

We built upon a 2017 review conducted by Reynolds et al. evaluating the impact of trauma systems components in low- and middle-income countries.14 The results of this review were expanded and restructured to include contemporary literature, as well as an emphasis on pragmatic interventions for civilian casualties of blast injury. The findings were organized by phase of care: lay first response, prehospital care, definitive care rendered at a health facility, and system-wide initiatives (e.g., data collection, program evaluation, and quality improvement). Findings of this review were then supplemented with qualitative thematic analysis of key informant interviews (KIIs) with HMA experts, providing insight into current organizational priorities, factors contributing to both successful and unsuccessful prior initiatives, and views on opportunities and obstacles to strengthen coordination between HMA and the emergency health response to civilian casualties of EO. These composite findings were then synthesized into key interventions along a continuum of care from the point of injury to definitive care at a health facility in accordance with the WHO Emergency Care System Framework (ECSF). The mortality reduction potential of these interventions was modeled using existing outcomes data across an integrated chain of post-blast care (Figure 1). Taking into account interactions across each phase of care, it was estimated that a 68 percent mortality reduction potential would be observed if all interventions were fully implemented.

We designated this innovative output the “Chain of Civilian Casualty Care” (CCCC). This integrated set of practices interfaces with the WHO Trauma Pathway and ECSF but focuses specifically on interventions that can be coordinated with existing activities conducted by mine action operators and the broader mine action sector (Figure 2).15,16 This was first presented at a plenary session, “Fulfilling the rights of survivors, from immediate responsive care to an independent, dignified life,” during the 26th International Meeting of Mine Action National Directors and United Nations Advisers in Geneva in June 2023. Opportunities for enhanced coordination between the HMA sector and emergency health response were explored at a side event at the intersessional meetings of the Anti-personnel Mine Ban Convention (APMBC) in June 2023 in Geneva with presentations by key actors including APMBC VA co-chairs, International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), and the WHO. These themes were further elaborated in a main panel session, “Prioritising access to health care services,” during the Third Global Conference on Victim Assistance to the Victims of Anti-Personnel Mines and Other Explosive Ordnance in Phnom Penh, Cambodia, in October 2023. The discussions held in these fora have generated significant momentum toward concrete implementation strategies.

Next Steps: Layperson First Responder Trainings

Given the demonstrated mortality reduction potential of LFR trainings and clear implementation opportunities, this intervention emerged as a high-priority target for an initial pilot collaboration. LFR trainings have been used to bring emergency care closer to the point of injury in settings with limited resources and incompletely developed prehospital systems.17,18,19,20 Such interventions are closely related to the objectives of Tactical Combat Casualty Care, the US military’s lifesaving first aid training for all non-medical personnel, which contributed to the reduction of preventable prehospital death by nearly 50 percent during the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan.21,22 The military’s emphasis on rapid hemorrhage control was translated to the civilian context in high-resource settings through initiatives such as the American College of Surgeons (ACS) Committee on Trauma (COT) Stop the Bleed Campaign.23 One of the most successful examples of LFR trainings in conflict and post-conflict settings occurred in the context of mine action. In the 1990s, investigators from the Tromsø Mine Victim Center trained LFRs in communities affected by landmines in Cambodia and Iraq, reducing mortality from 40 percent to 15 percent over a five-year period.24,25,26,27

Despite these positive outcomes, LFR trainings have not been widely adopted or scaled in a coordinated and sustainable manner. Numerous LFR trainings have been conducted in non-conflict settings. These trainings have targeted various populations, often emphasizing commercial drivers, and have demonstrated positive outcomes on trainee knowledge and skill.28,29,30 However, these trainings were conducted as isolated interventions without clear pathways to scale or integration with larger health and trauma care systems. Significant implementation gaps exist, including inadequate understanding of sociocultural acceptability and strategies for context-specific adaptation; methods for ensuring adequate representation of women and underserved groups; evaluation of facilitators and barriers to sustainable uptake; and implementation toolkits for deployment of LFR trainings to promote dissemination.

We plan to address these issues by conducting a novel joint delivery model partnering mine action operators with trauma care providers to conduct LFR trainings with a training-of-trainers (ToT) approach in communities affected by EO as the first step in the implementation of the CCCC. Burkina Faso has been identified as a pilot context for a mixed-methods evaluation on the deployment of LFR trauma trainings from which initial implementation toolkits will be developed. This project leverages both local and multilateral partnerships with the Mine Action Area of Responsibility, UNMAS, and Mines Advisory Group (MAG), as well as technical advisory input from the WHO and International Federation of the Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC) in close collaboration with Burkinabe partners such as the NGO Pull for Progress. Trainings targeting civil servants and community health workers will include the WHO’s Community First Aid Responders and associated conflict package. For community members, a CCCC version of the IFRC’s Community-Based First Aid trainings will be developed with enhanced content for blast injury such as burn first aid and a context-appropriate adaptation of the ACS Stop the Bleed training for hemorrhage control. These practices draw heavily from the work of the Tromsø Mine Victim Center.31 CCCC LFR training content will be cross-referenced with the ICRC provider-focused Blast Trauma Care training course to ensure consistency.32 LFR trainings will also be delivered through integration with existing EORE activities in partnership with MAG during this initial pilot.

For subsequent initiatives, depending on the organizational structure of the partnering mine action operator, trainings could also be conducted through coordination with team medics in a manner that does not interfere with primary responsibilities at clearance sites. The specific aims of this pilot project are to:

Conduct baseline needs assessment to define the highest-yield target populations among communities affected by EO, assess the cultural acceptability of LFR trauma trainings, and elucidate barriers to inclusion among women and marginalized groups. The design of this pilot will be informed by a baseline needs assessment via KIIs, focal group discussions, and actor mapping to define inclusive recruitment strategies, engaging local and HMA stakeholders to ensure the proposed intervention is feasible and context appropriate.

Assess the impact of LFR trauma training delivered in partnership with mine action operators on the first aid practices of LFRs trained in Burkina Faso and the fidelity of subsequent LFR trainings as delivered by local trainers through a ToT model. We will utilize previously validated instruments in conjunction with structured clinical scenarios to assess the impact of LFR trainings on participant knowledge and skill with standardized pre- and post-course assessments, as well as longitudinal follow-up at six months. Based on these assessments, as well as evaluation of nontechnical skills, ToT candidates will be recruited and trained to ensure local ownership and sustainability of the intervention. Fidelity of trainings led by local trainers to the original curriculum will be assessed to evaluate ToT efficacy. This project phase will also entail development of open-access LFR trauma training materials with enhanced content on blast injury for use in other contexts.

Develop implementation toolkits for coordination between HMA stakeholders and trauma care providers to deliver LFR trainings in communities affected by EW. Using implementation science principles, we will assess the acceptability, feasibility, penetration, and sustainability of LFR trainings delivered through this model.33 The output of this process will be a toolkit for implementation guidance on community-based LFR trainings in conflict-affected settings via a joint delivery model by partnering mine action operators with trauma care providers. This will include guidance on precautions taken by first responders to avoid becoming victims of EO themselves. Included in this process will be pathways to ultimately transfer ownership of such programs to national mine action authorities, host governments through their Ministries of Health, and other local stakeholders to ensure sustainability. Implementation strategies will build from existing infrastructure to facilitate uptake, with standardized processes for monitoring and evaluation (M&E) to identify opportunities for system-wide improvement. HMA stakeholders are well-placed to contribute to robust data collection and M&E given the sector-wide precedent for high-quality standardized data collection through IMAS 5.10 on information management.34 This presents a unique opportunity to extend these practices to the health sector in complex operational environments and newly implemented trauma care initiatives.

Leveraging local and multilateral partnerships with enhanced cooperation between HMA and trauma care providers, this project has system-wide implications for humanitarian response in settings affected by EO. Next steps to advance this initiative will include: 1) scaling and adaptation of co-delivered LFR trainings in other conflict-affected settings regionally and globally, and 2) improved coordination with local health facilities receiving casualties to collect longitudinal data linking the impact of LFR trainings with clinical outcomes of casualties of EO and conflict-related injury more broadly. Policy and advocacy targets can focus on adapting research outputs to evidence-based policy briefs encouraging consideration for the inclusion of collaborative LFR trainings and the CCCC into future commitments such as the next action plan of the States Parties 2025–2029 to be adopted by the Fifth Review Conference to take place in Siem Reap, Cambodia, in 2024. These efforts can also inform amendments of IMAS 13.10 regarding an expanded role of HMA stakeholders to include the delivery of LFR trainings to communities affected by EO.

Conclusion

The MA-TCC aims to promote strategic cooperation between HMA and the emergency health response to civilian casualties of EO. This initiative has the potential to be scaled across EO-affected conflict and post-conflict settings globally, thereby improving coordination between the health and protection sectors at a broader level within the global humanitarian system. The CCCC is an overarching structure designed to guide this process by outlining opportunities for enhanced partnership through evidence-based interventions to reduce mortality from trauma in low-resource settings. While the ultimate responsibility for strengthening trauma systems in conflict-affected settings lies with parties to conflict and health authorities, the CCCC highlights concrete ways in which HMA stakeholders can potentiate these efforts. At a time when indiscriminate use of EO and its continued impact disproportionately affect civilians in conflicts globally, developing a coordinated mechanism to improve cooperation between HMA and emergency health responders has the potential to significantly reduce preventable death and impairment among casualties.

See endnotes below.

The International Blast Injury Research Network (IBRN) is a trans-disciplinary network launched by the University of Southampton after identifying that leading blast research was primarily focused on military rather than civilian situations and perspectives. Addressing this gap, the multidisciplinary IBRN team was founded to improve research within the civilian context and at a holistic level. The IBRN catalyzes dialogue between the fields of Blast Engineering & Injury Modelling; Public Health; Epidemiology; Traumatology and Critical Care; Operational Research; and Clinical Informatics. This network fosters collaboration among a range of stakeholders including academics, clinicians, and humanitarian organizations to facilitate a broad portfolio of multidisciplinary research into the humanitarian consequences of blast injury.

Hannah Wild is a General Surgery Resident at the University of Washington focused on humanitarian response for civilian casualties in conflict settings. She received her undergraduate degree from Harvard University and MD from Stanford University. Her research focuses on improving humanitarian surgical care for civilian casualties in conflict settings, particularly for victims of explosive weapons (EW). In collaboration with the International Blast Injury Research Network and United Nations Mine Action Service (UNMAS), she leads the Mine Action Trauma Care Collaborative (MA-TCC), an effort to strengthen coordination between the mine action sector and trauma care for casualties of EW.

Hannah Wild is a General Surgery Resident at the University of Washington focused on humanitarian response for civilian casualties in conflict settings. She received her undergraduate degree from Harvard University and MD from Stanford University. Her research focuses on improving humanitarian surgical care for civilian casualties in conflict settings, particularly for victims of explosive weapons (EW). In collaboration with the International Blast Injury Research Network and United Nations Mine Action Service (UNMAS), she leads the Mine Action Trauma Care Collaborative (MA-TCC), an effort to strengthen coordination between the mine action sector and trauma care for casualties of EW.

Ms. Christelle Loupforest is the Officer-in-Charge of the UNMAS Office in Geneva. In her twenty-five years of service with the United Nations, she served in the Department of Peace Operations, the Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, the UN/OAS Human Rights Mission in Haiti, and at the World Health Organization (WHO). She holds a Master of Political Science and speaks English, French, and Spanish.

Ms. Christelle Loupforest is the Officer-in-Charge of the UNMAS Office in Geneva. In her twenty-five years of service with the United Nations, she served in the Department of Peace Operations, the Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, the UN/OAS Human Rights Mission in Haiti, and at the World Health Organization (WHO). She holds a Master of Political Science and speaks English, French, and Spanish.

Loren Persi has been conducting research on victim assistance since 2004. Persi holds a double degree in development studies and Asian societies at the Australian National University and a Master of Political Science (Peace Studies) from the University of Belgrade. He is the impact research team leader at International Campaign to Ban Landmines and previously worked as a research consultant with the Geneva Academy of International Humanitarian Law and Human Rights on global conflict casualty recording, with UNDP in Southeast Europe on regional small arms control, Humanity & Inclusion on victims’ rights and disarmament advocacy, and with Standing Tall Australia on the legislation and implementation of victim assistance.

Loren Persi has been conducting research on victim assistance since 2004. Persi holds a double degree in development studies and Asian societies at the Australian National University and a Master of Political Science (Peace Studies) from the University of Belgrade. He is the impact research team leader at International Campaign to Ban Landmines and previously worked as a research consultant with the Geneva Academy of International Humanitarian Law and Human Rights on global conflict casualty recording, with UNDP in Southeast Europe on regional small arms control, Humanity & Inclusion on victims’ rights and disarmament advocacy, and with Standing Tall Australia on the legislation and implementation of victim assistance.

Elke Hottentot has worked in the field of international development, humanitarian action, and community development for thirty years. Her specialization is in the areas of humanitarian mine action, with a specific focus on victim assistance, as well as disability-inclusion, community rehabilitation, and participatory development. Within these areas, she has held a wide variety of roles, including policy lead, technical adviser, university lecturer, researcher, community health center manager, evaluator, trainer, and co-coordinator of the Mine Action Area of Responsibility of the Global Protection Cluster. She has worked with international, national, and local nongovernmental and grassroots organizations, public and private health facilities, as well as the United Nations in Southeast Asia, Africa, South America, the Caribbean, the Middle East, Canada, and Europe, and is currently based in Geneva, Switzerland.

Elke Hottentot has worked in the field of international development, humanitarian action, and community development for thirty years. Her specialization is in the areas of humanitarian mine action, with a specific focus on victim assistance, as well as disability-inclusion, community rehabilitation, and participatory development. Within these areas, she has held a wide variety of roles, including policy lead, technical adviser, university lecturer, researcher, community health center manager, evaluator, trainer, and co-coordinator of the Mine Action Area of Responsibility of the Global Protection Cluster. She has worked with international, national, and local nongovernmental and grassroots organizations, public and private health facilities, as well as the United Nations in Southeast Asia, Africa, South America, the Caribbean, the Middle East, Canada, and Europe, and is currently based in Geneva, Switzerland.

Sebastian Kasack holds a master’s degree in geography and has been involved in mine action since 1996, working for international NGOs, UNMAS, UNICEF, and UNDP. In 2016, he joined Mines Advisory Group (MAG) as a senior technical advisor. On victim assistance, he authored the UNICEF publication: “Assistance to Victims of Landmines and Explosive Remnants of War Guidance on child-focused victim assistance.”

Sebastian Kasack holds a master’s degree in geography and has been involved in mine action since 1996, working for international NGOs, UNMAS, UNICEF, and UNDP. In 2016, he joined Mines Advisory Group (MAG) as a senior technical advisor. On victim assistance, he authored the UNICEF publication: “Assistance to Victims of Landmines and Explosive Remnants of War Guidance on child-focused victim assistance.”

Firoz Alizada is an Implementation Support Officer with the Anti-Personnel Mine Ban Convention’s substantive secretariat, the Implementation Support Unit (ISU) in Geneva. His work includes supporting States Parties to the Convention in implementing victim assistance provisions. He has extensive experience working in victim assistance/disability rights and humanitarian disarmament including with the International Campaign to Ban Landmines, UNMAS, Humanity & Inclusion, the International Committee of the Red Cross, and local survivors’ networks in Afghanistan. He holds an executive master’s in development policy and practice from the Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies of Geneva.

Firoz Alizada is an Implementation Support Officer with the Anti-Personnel Mine Ban Convention’s substantive secretariat, the Implementation Support Unit (ISU) in Geneva. His work includes supporting States Parties to the Convention in implementing victim assistance provisions. He has extensive experience working in victim assistance/disability rights and humanitarian disarmament including with the International Campaign to Ban Landmines, UNMAS, Humanity & Inclusion, the International Committee of the Red Cross, and local survivors’ networks in Afghanistan. He holds an executive master’s in development policy and practice from the Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies of Geneva.

Adam L. Kushner, MD, MPH, FACS, has worked as a surgeon, educator, and researcher in dozens of countries. He is President of A.L. Kushner & Associates, a global surgery and global health consulting firm. He was a founder of Surgeons OverSeas and a subject matter expert on human rights, humanitarian assistance, and disaster relief for the US military. He has authored over 150 peer-reviewed papers and edited three books on global surgery. He completed his general surgery residency at the University of Texas Health Science Center-San Antonio; MD at the Mount Sinai School of Medicine; MPH at Johns Hopkins School of Public Health; and BA in History and International Relations at Cornell University. He currently resides in Anchorage, Alaska, where he spends his summers fishing for salmon.

Adam L. Kushner, MD, MPH, FACS, has worked as a surgeon, educator, and researcher in dozens of countries. He is President of A.L. Kushner & Associates, a global surgery and global health consulting firm. He was a founder of Surgeons OverSeas and a subject matter expert on human rights, humanitarian assistance, and disaster relief for the US military. He has authored over 150 peer-reviewed papers and edited three books on global surgery. He completed his general surgery residency at the University of Texas Health Science Center-San Antonio; MD at the Mount Sinai School of Medicine; MPH at Johns Hopkins School of Public Health; and BA in History and International Relations at Cornell University. He currently resides in Anchorage, Alaska, where he spends his summers fishing for salmon.

Dr. Barclay Stewart, MD, PhD, is a trauma and burn surgeon at the University of Washington. His research foci include global injury prevention/control, developing models of care for the injured feasible in low-resource settings, and benchmarking quality of care using long-term patient-reported outcomes.

Dr. Barclay Stewart, MD, PhD, is a trauma and burn surgeon at the University of Washington. His research foci include global injury prevention/control, developing models of care for the injured feasible in low-resource settings, and benchmarking quality of care using long-term patient-reported outcomes.