Mine Action and the Triple Nexus

By Markus Schindler [ Fondation Suisse de Déminage, FSD ]

CISR Journal

This article is brought to you by the Center for International Stabilization and Recovery (CISR) from issue 27.1 of The Journal of Conventional Weapons Destruction available on the JMU Scholarly Commons and Issuu.com.

In less than a decade, the term “triple nexus” has matured from the technical parlance of donor agencies’ policy papers to a widely recognized concept among aid workers. It advocates for closer integration of humanitarian aid, development, and peacebuilding efforts to produce combined effects. The five pillars of humanitarian mine action (HMA) are widely considered to contribute to each of the sectors that make up the triple nexus. However, there are many approaches on how to conceptualize HMA within the humanitarian, development, and peacebuilding nexus. This article explores three approaches and highlights their respective caveats before developing suggestions on how to improve triple nexus sensitive HMA programming.

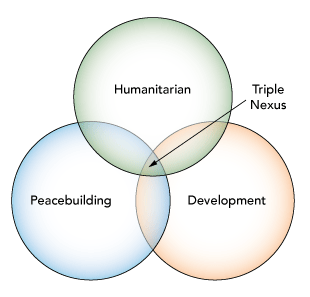

Figure 1. Problem statement: Humanitarian, development, and peace sectors largely separate, limited overlap.

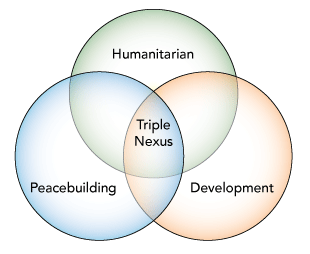

Figure 2. Triple Nexus mission: More collaborative, coherent, and complementary humanitarian, development, and peace actions.

Introduction

Government funders of humanitarian aid brought to prominence the concept of the Humanitarian-Development Nexus during the 2016 World Humanitarian Summit in an attempt to promote greater collaboration between organizations working in short-term humanitarian aid and long-term international development.1 Later that year, the newly-elected UN Secretary-General António Guterres remarked that “humanitarian response, sustainable development, and sustaining peace are three sides of the same triangle.”2

Taking this idea forward, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD)—an institution comprised of the world’s leading donors—through its Development Assistance Committee (DAC) formalized the new concept as the Humanitarian-Development-Peace Nexus: An approach with the goal to increase coordination and cooperation between humanitarian, development, and peace efforts with the goal to meet peoples’ needs more effectively.3 Since then, many donors have embraced the “triple nexus” concept, and have, for their part, asked HMA partners to follow suit.

This article explores three approaches in locating mine action within the triple nexus. The first is descriptive: It seeks to explain how mine action in its current form fits into the nexus of humanitarian, development, and peace efforts. The second approach is normative: Donor agencies specifically ask mine action organizations to design programs in ways that not only further humanitarian goals but also contribute to development and peacebuilding. The third approach is to design holistic programs that include expertise from all sectors within the triple nexus, including HMA. Such programs require coordination and collaboration between several organizations specializing in the humanitarian, development, and peacebuilding sectors, respectively, for example through forming a consortium.

Describing Mine Action within the Triple Nexus

“The land was not used due to risks of mines and ERW, but after the land was cleared and handed over by FSD it was changed to a garden with apple trees and agriculture land for cultivating onions.”

~Nazer Shah, land owner, Badakhshan Province, Afghanistan, October 2019

Having committed to supporting and incentivizing activities that further the triple nexus approach, many international donors, scholars, and institutional researchers are interested to learn how the five pillars of mine action are at the “nexus” of humanitarian, development, and peace efforts.4 Common questions include how HMA and conventional weapons destruction (CWD) programs are contributing to conflict de-escalation, post-conflict development, and peacebuilding in conflict-ravaged environments.

The contributions of HMA (as well as most other types of interventions) can be divided into two types: Contributions resulting from the product of HMA, such as released land, and contributions that arise from the process of implementing HMA programs.

Product. Post-conflict development requires physical space—land on which development activities can take place. However, the risk of contamination with explosive hazards makes land in post-conflict societies inaccessible, resulting in reduced development activities, particularly in the areas most affected by prior conflicts. The release of land through HMA tackles this problem by allowing access to previously unsafe areas, making them available for post-conflict recovery activities. Mine action enables and, thereby, often contributes to economic recovery through land release by providing one of the key conditions for development to occur.

Access to previously inaccessible land makes subsequent improvements possible. Development of released land can result in sustainable landscapes and increased environmental resiliency, for example through the expansion of irrigation systems and the planting of crops and trees in previously barren areas. Aside from positive environmental impacts, sustainable landscapes also provide significant economic, social, and environmental benefits to affected populations.

A significant result of HMA activities is the potential improvement in physical capital and infrastructure. Aside from rural electrification and enhanced water and sanitation systems, studies show that the clearance of transportation networks and trade hubs in particular improve market access and stimulate economic activity.5 Access to transportation routes and road construction reduces both travel times and transportation costs, and contributes to the diversification of primary production. Additionally, improved road infrastructure allows populations in post-conflict areas to participate in market activities, leading to economic empowerment of people affected by explosive hazards.

Previously barren, IED-contaminated land being used for irrigation and agriculture in Northern Iraq one year after clearance by Shareteah Humanitarian Organisation (SHO). Image courtesy of SHO.

Economic empowerment of mine-affected populations is also a result of victim assistance programs that seek to empower its most marginalized and vulnerable members through reintegration into their communities as well as into the local economy.

The output of HMA and particularly CWD also translates to improvements of national security: Unexploded ordnance (UXO) and loose stockpiles of mines and other munitions can be captured and used by non-state armed groups (NSAG), either conventionally or to build improvised explosive devices (IEDs). Meanwhile, the proliferation of anti-aircraft weapons, especially shoulder-fired MANPADS6 can pose a serious threat to civil aviation. Mine action and CWD organizations can bolster a country’s national security by contributing to CWD—the coordinated destruction of surplus and degraded stocks of explosive ordnance (EO) as well as small arms and light weapons (SALW) and their ammunition. This and related activities, such as training in physical security and stockpile management (PSSM), lead to smaller, better-secured stockpiles and reduce the risk of their diversion to NSAGs. Mine action and CWD thereby contribute to the strengthening of national security in post-conflict societies.

Process. The process of implementing HMA/CWD programs in itself contributes to a variety of social goods. For example, Fondation Suisse de Déminage (FSD) implements an HMA program in the southern Philippines, which supports the coordination of UXO spot tasks between state security forces and NSAGs. This allows explosive ordnance disposal (EOD) teams of the former to safely access and render safe items found in areas with a strong presence of the latter. This not only results in a reduction of explosive hazards, it also facilitates coordination on tangible issues with immediate positive outcomes and helps to build rapport and trust between mid- and low-ranking members of state security forces and NSAGs—an important aspect of conflict de-escalation that is often overseen by high-level peace talks.

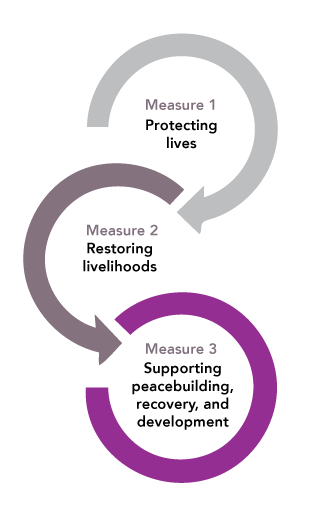

Figure 3. UNDP’s conceptualization of mine action program contribution, articulated in three measurement and focus areas. United Nations Development Programme (UNDP): Mine Action for Sustainable Development (New York, NY: June 2016), p. 21.

As a highly specialized and regulated sector, mine action also contributes to capacity-building and localization: Members of mine-affected communities make up the bulk of all HMA staff, while many countries, as well as institutional donors, encourage the formation of national mine action nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) that can build on the skill set that has been developed over years of HMA work.

Capacity-building also happens on a national scale. While other humanitarian efforts are often primarily coordinated within UN clusters and on local political levels, most countries set mine action priorities and coordinate mine action activities in great detail on a national level through national mine action authorities and/or centers (NMAA/NMAC). These bodies often receive support from UN agencies and international mine action organizations. Their collaboration and cooperation on immediate issues that produce tangible results contributes to the strengthening and professionalization of national institutions.

These examples notwithstanding, there is a notable scarcity of publications and studies on how mine action currently contributes to triple nexus goals.7 Of the available works, most emphasize that surveying the contributions of mine action activities on development and peacebuilding are a complex and resource-intensive endeavor, particularly when done on a large, nation-wide scale, as (a) the timeframes and scales for measuring changes in these sectors based on tangible indicators are often beyond the scope of mine action programs; and (b) mine action is being conducted in environments with a myriad of other external factors that contribute towards (or disrupt) triple nexus goals, in most cases far too many to control for in any serious study.

However, reducing the scope from country-level indicators to the local level presents a variety of challenges. Despite the increased assessment of medium- to long-term impacts of HMA activities on beneficiary communities, the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) notes that “there has been no consistent and rigorous way of measuring the socio-economic impact of mine action.”8 Obtaining information on the progress of peacebuilding on the local level is even more difficult. For one, the methodology and practices in measuring the impact of peacebuilding programs are often highly contingent on the respective context and generally not as well established as those of other triple nexus sectors.9 Moreover, most HMA organizations are not well-equipped to measure changes regarding peace and security, leaving HMA actors to resort to community surveys recording local perceptions of peace that only offer a very temporary glimpse of the situation and at times fail to reflect wider trends.10 On the other hand, regional or local data sets on peace and security are less often available compared to nation-wide data, and the more tangible events in peacebuilding often happen on the national level.

Example of capacity development as an FSD Technical Advisor conducts training for an operator from Iraqi NGO Shareteah Humanitarian Organisation (SHO). Image courtesy of FSD.

Armored excavator from FSD’s mechanical clearance team in Iraq removing rubble so that villagers can return to their land and rebuild their homes and livelihoods. Image courtesy of FSD.

Nevertheless, to some, the contributions listed previously are already examples of how mine action operates in and expands the overlap between the sectors of the triple nexus. However, others seek to explore how mine action needs to adapt its current philosophies and practices to better integrate triple nexus goals.

Calling for Mine Action within the Triple Nexus

Far more than an academic exercise, in many instances the appeal to locate mine action within the triple nexus is normative in nature: A call by the international donor community to mine action actors to design their programs holistically and to ensure that their activities, traditionally understood as part of the humanitarian sector, tangibly contribute to the achievement of development and peacebuilding goals.

In principle, expanding the scope of mine action organizations and their activities into other sectors of the triple nexus is relatively unproblematic. The vast majority of tasks and routines of humanitarian, development, and peacebuilding NGOs in any given context are virtually the same: administration and HR in accordance with local labor laws; budgeting; accounting; reporting to donors and other stakeholders; procurement and logistics; renting offices; registering vehicles; managing staff; monitoring and evaluating projects; assessing security risks; designing and applying policies; writing grant proposals; reporting to and coordinating within the cluster system or similar setups; etc. Skill sets, expertise, and experience within particular sectors and their sub-branches, though by no means immaterial, can be transferred and acquired with relative ease. Experienced staff can be hired, consultants can be contracted, and employees can be trained. However, there are a number of systemic obstacles that restrain mine action organizations from expanding their programming to a more holistic range—one that would increase the overlap between the triple nexus sectors.

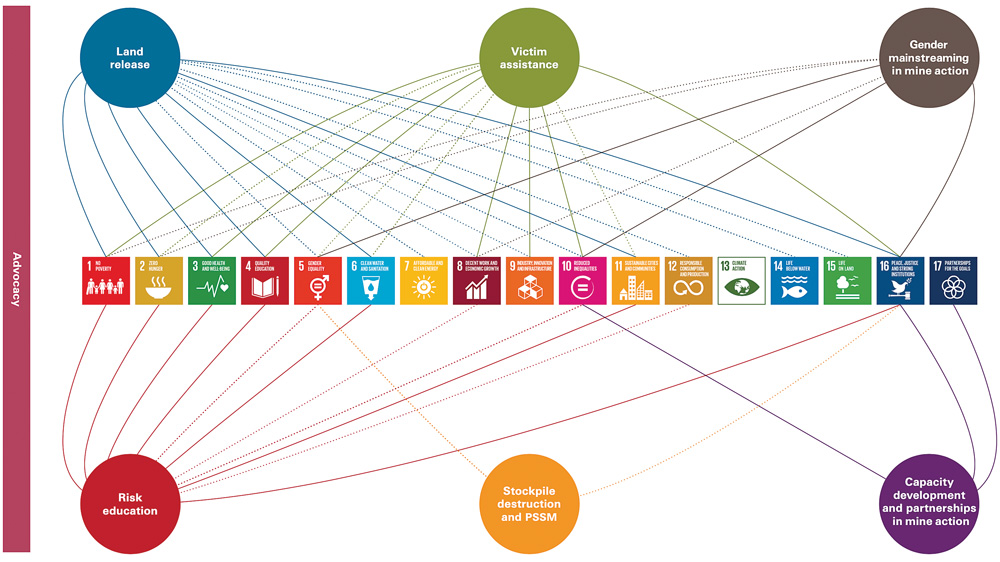

Figure 4. Direct and indirect links between mine action and the Sustainable Development Goals. GICHD-UNDP: Mine action and the Sustainable Development Goals, p. 29.

Firstly, the international donor community funds mine action primarily from monies set aside for humanitarian assistance—a pot that is significantly smaller than that for development assistance.11 If the same government agencies and UN structures that fund mine action would begin to contribute to more holistic approaches that link HMA action with other humanitarian, development, and peacebuilding goals, this would reduce funding available specifically for HMA efforts. Less land would be released, fewer victims would be supported, and risk education sessions would reduce in number. As a result, donor agencies that fund particular activities are often reluctant—or restrained—to spend their limited funds outside of their mandated core areas. At the same time, collaboration between institutional donors’ internal agencies is often bureaucratic and time-consuming, making funding for holistic triple nexus-sensitive programming difficult.

Secondly, NGOs and UN agencies often define their mandates in ways that focus primarily on activities rather than end effects. This ultimately restricts them to their original fields of operations, which are typically linked to the previously mentioned compartmentalized pots of donor money.

If positioning HMA within the triple nexus is too challenging a task for mine action organizations to do on their own, one alternative would be to work together with aid organizations from outside the HMA sector.

Mine Action as a Component of Triple Nexus Cooperation

In its Recommendation on the Humanitarian-Development-Peace Nexus, the OECD’s Development Assistance Committee encourages adherents to “support, incentivise, and implement more collaborative, coherent, and complementary humanitarian, development, and peace actions.”12 The document emphasizes the need for coordination and cooperation between actors in each of the sectors and joined-up, multi-stakeholder programming within the triple nexus.

Socioeconomic impact assessment—trees cut by locals on land that was cleared and handed over by FSD in Afghanistan. Image courtesy of FSD.

Understood in this way, locating HMA within the triple nexus means linking mine action programming with other efforts within the triple nexus, with the aim to generate synergies between humanitarian, development, and peacebuilding programming that are greater than the sum of their separate impacts. While this approach to the triple nexus enjoys prevalence among many representatives from donor nations and UN aid agencies, there are yet a number of caveats that need to be considered. For one, the challenges to obtain funding for holistic, triple nexus-sensitive HMA programming outlined in the previous section affect joined-up triple nexus programming in similar ways. However, there are also other issues that require consideration.

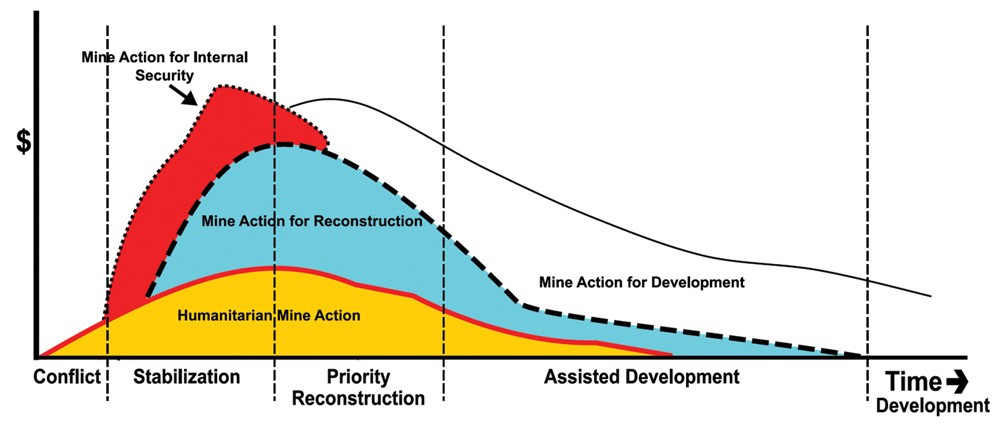

During and post-conflict, the three aspects of the triple nexus do not usually gain prominence at the same time. Mine action experts Ted Paterson and Eric Filippino therefore suggest that mine action can—broadly speaking—be placed “within four main stages of a country’s conflict and subsequent recovery:

- Conflict

- Immediate, post-conflict stabilisation

(including peacekeeping/peace-building) - Reconstruction

- Traditional development”13

While these stages and the required mine action response may at times overlap, their respective prominence and relevance wax and wane over time, making space for subsequent stages. For example, during and in the immediate aftermath of a conflict, mine action responses will primarily focus on humanitarian and internal security needs; however, with increasing stability and security, mine action will transition to contribute primarily to development needs.

Created at a time when peacebuilding was not yet considered part of the nexus, this argument applies to it as much as it does to development. Peacebuilding, too, has a variety of components and stages that become relevant at different times within a given (post-) conflict environment, and that may, respectively, be linked with specifically targeted mine action activities.

While Paterson and Filippino urge mine action planners and managers to “forge earlier and stronger links to a country’s development efforts,” such connections require the buy-in of key actors within the national development planning processes, and will likely not yield many tangible results in the early stages of a mine action program.14 This means that mine action can indeed contribute to all aspects of the triple nexus; however, the respective extent of each contribution is largely contingent on external factors, such as the stage of a country’s conflict or recovery.

Lessons Learned and Ways Forward

A brief glance at the agendas of donor conferences of late leaves little doubt that the demand for HMA programming to be sensitive to the humanitarian, development, and peace nexus is only set to increase. Nevertheless, there are still a variety of disparate approaches, a lack of consensus about the meaning of the concept, and above all, a number of structural barriers that need to be resolved before triple nexus-sensitive HMA programming can reach its full potential.

Figure 5. Stages of a mine action program. Figure courtesy of Ted Paterson and Eric Filippino: Mine Action and Development, p. 55.

Mine action organizations can address this challenge in many ways. A fast and simple way forward is to design project outcomes and indicators that better document HMA contributions to sustainable development and peacebuilding. More than words are needed, however, to achieve actual progress toward this goal. What is truly required is the strengthening of linkages with other humanitarian organizations and improved coordination between mine action NGOs and actors in development and peacebuilding. Moreover, HMA organizations need to learn to become more flexible and results-focused in their overall mission and their programming on the ground.

Such changes are only possible if they receive the strong support of donors, not only in encouraging words but, above all, in delivering better, more flexible, long-term financing. This is far from a new insight. The OECD has early on called on its adherents to “use predictable, flexible, multi-year financing” and to identify “financing mechanisms that bring together humanitarian, development and peace stakeholders.”15 Governmental and institutional donor agencies need to do more to develop funding mechanisms that bridge departmental trenches and that are compatible with the triple nexus’ multi-year and multi-stakeholder approach. Only then can holistic programming and nexus-focused approaches be rolled out to full effect. Mine action organizations are ready to play their part.

Markus Schindler

Project Manager

Fondation Suisse de Déminage (FSD)

Markus Schindler is currently a Project Manager for Fondation Suisse de Déminage (FSD) in Iraq, where he is leading a capacity development project that aims to build the professional competence of a local mine action NGO. His experience spans eight years working with FSD in various roles spread across multiple countries, including Afghanistan, Tajikistan, and the Philippines. Schindler holds a Master’s Degree in Strategic Studies from University College Cork, a Master’s Degree in Social Science and Ethics from Ruhr University Bochum, and a Bachelor’s Degree in Philosophy from the University of Regensburg.

Markus Schindler is currently a Project Manager for Fondation Suisse de Déminage (FSD) in Iraq, where he is leading a capacity development project that aims to build the professional competence of a local mine action NGO. His experience spans eight years working with FSD in various roles spread across multiple countries, including Afghanistan, Tajikistan, and the Philippines. Schindler holds a Master’s Degree in Strategic Studies from University College Cork, a Master’s Degree in Social Science and Ethics from Ruhr University Bochum, and a Bachelor’s Degree in Philosophy from the University of Regensburg.