Hidden Crisis in Borno State

CISRThis article is brought to you by the Center for International Stabilization and Recovery (CISR) from issue 25.2 of The Journal of Conventional Weapons Destruction available on the JMU Scholarly Commons and Issuu.com.

By Sean Sutton [ MAG, Mines Advisory Group ]

These images were projected at the International Festival of Photojournalism, Visa Pour l’Image in France, September 2021.

At the end of 2019, Nigeria reported a significant increase of landmine, explosive remnants of war (ERW), and improvised explosive device (IED) contamination in its states. In 2019 alone, a total of 239 known mine casualties were recorded in Nigeria. Although the exact amount of contamination in Nigeria today is unknown, the Landmine & Cluster Munition Monitor asserts that Borno is the most heavily affected state in the country. Due to mounting mine contamination and increasing pressure from non-state armed groups (NSAG), internally displaced persons (IDPs) and communities are unable to safely return to the region.

Extensive landmine use by Boko Haram has created a state of crisis in the region and the number of casualties continues to grow. The United Nations Mine Action Service (UNMAS) reported in late 2020 that NSAG were more frequently targeting civilian populations. The conflict between NSAG and the local military has been steadily depositing explosive devices throughout the region, including improvised devices using adapted submunitions.

The hostile situation has led to a shortage of resources for the distressed communities and a lack of humanitarian access, impeding recovery efforts. Farmer and civilian casualties continue to climb as people are displaced, unable to return to their homes for fear of their safety.

I travelled to Borno State, northeast Nigeria, for six weeks in October and November 2020 to document life in internally displaced persons (IDP) camps, the impact of the current conflict on people, and Mines Advisory Group’s (MAG’s) work there. Explosive ordnance—improvised landmines and unexploded ordnance—is part of this story. In Nigeria, I documented MAG’s work: helping people to be safer in a dangerous environment through risk education and gathering evidence of hazardous contaminated areas.

I spent some time in and around the state capital of Maiduguri and travelled by helicopter a number of times to government-controlled towns and enclaves (referred to as local government areas [LGAs]). Due to frequent ambushes, travelling by road is unadvised and only by convoy with a military escort when possible. Improvised landmines are often used in these attacks.

I also spent time in Bama and Gwoza, strategically important towns previously controlled by Boko Haram. Gwoza was named by Boko Haram as their “califate capital” until the army wrestled it back in 2015. These LGAs come under regular attacks and many people searching for firewood or in their daily farming activities have been killed and abducted as they head out across the defensive anti-vehicle trench lines.

In a makeshift unofficial camp for IDPs displaced by the conflict in Maiduguri, Modu Amara explained what had happened to his village and his people:

The insurgents came into the village with vehicles shooting at 5 p.m. in the evening. They fired everywhere and we all ran to the bush as quick as we could. We came back the next day and everything was burnt. Two children had been burnt in a house. All the animals were killed. All was gone so we had to come here to Maiduguri.

Woodcutters are paid to chop tree trunks for firewood, a precious resource in the camps.

Mamza and her friend Falmata were badly injured when Falmata’s nine-year-old grandson Mustapha detonated a rocket-propelled grenade he was playing with. Mustapha and his fourteen-year-old uncle Bakura thought the grenade was part of the water pump and brought it back to the IDP camp where they shelter in Maiduguri. Mustapha was killed instantly in the explosion. Bakura survived.

Falmata is one of MAG’s trained focal points for landmine and explosive ordnance reports in one of Maiduguri’s IDP camps and is very supportive of the work MAG has been doing here. Her husband Umar is the main Bulama or village chief, senior to the ten other Bulamas in the camp. They have nine of their own children as well as four adopted orphans. I met her in her smoky kitchen on a wobbly bench, as one of her children tended a steaming pot in the background:

It is important work, people often find dangerous explosives and its thanks to MAG that they know what is dangerous. Just two weeks ago, a woman reported to me that she had found something on a wire near a school 3 km up the road. I went and looked—from a distance—and saw a milk tin with a wire. I told the military and they dealt with it. An old woman was out fetching firewood. She found a hollow log with a big bomb inside it. She reported it to the military at the gate, and they blew it up. She recognized it because of MAG. The work—it is good and it saves lives.

The village of Maiborti is 15 km south of Maiduguri on the road to Damboa. The attack mentioned previously happened in 2018. Since abandoning the burnt-out village, people have been going back to farm and they have paid a great price for doing so.

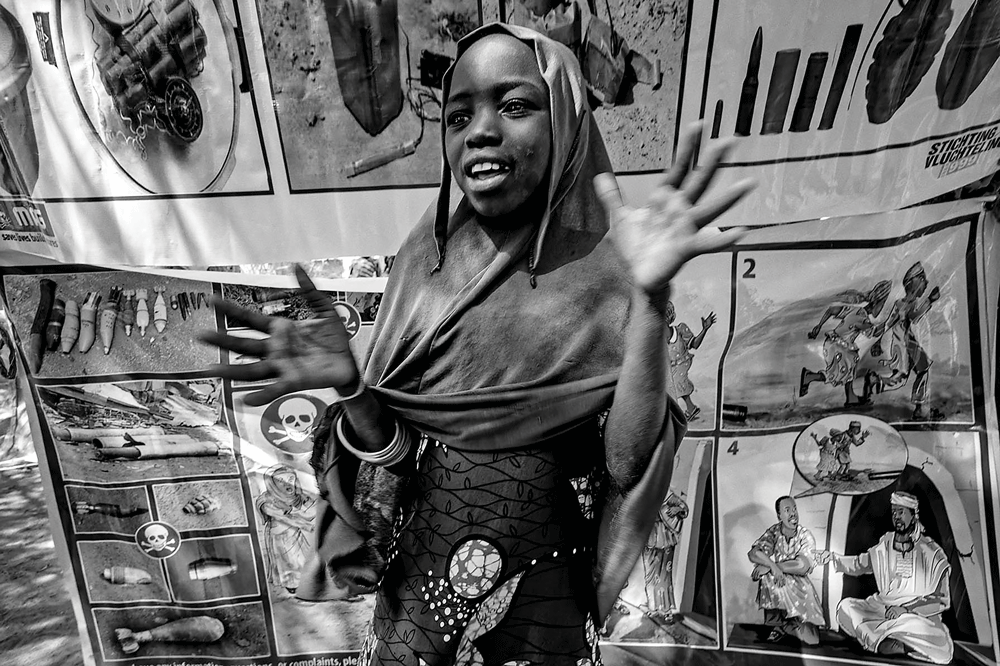

Akila, Usman, and Rukiya use large posters depicting improvised landmines made from everyday items: cooking pots, jerry cans, and tins. Other explosive threats like mortar bombs, rockets, and machine-gun ammunition feature along with caricatures demonstrating safe and good as well as dangerous and bad behavior. The highly experienced and skilled communicators guide the captivated audiences through the lessons. What should you look out for? What should you do if you are suspicious of something or an area? Who should you report it too? This frequently leads to reports of dangerous areas or locations of dangerous items.

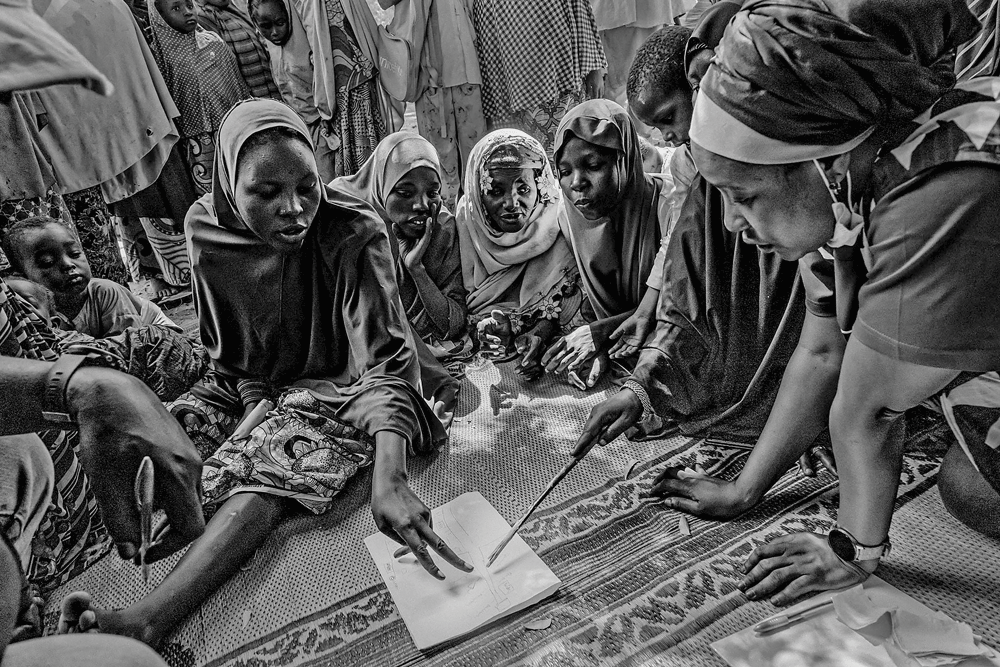

The teams work with focus groups on gathering information and mapping it. During Contamination Baseline Assessments, roads, rivers, villages, and landmarks are drawn into the dust. Stones, leaves, and branches are useful props, marking houses, suspected landmines, or explosive ordnance. People are very animated and deep discussions ensue. The agreed map is then drawn on paper with all the information gathered and noted in detail. This local knowledge is very valuable and helps determine dangerous areas that can help prioritize clearance for safe returns as and when the security situation allows.

Everyone here has a story, and Thlawur’s is no exception. During a lunchtime break, protected from the searing sun by the shade of a big tree, she told me her story:

I have suffered in the conflict but now I am helping others to survive. I started working with MAG in 2017. My family was living in Baga (on the shores of Lake Chad), but we had to leave because of insurgents in 2012 and we moved to Dele where we stayed until July 2014. When Boko Haram attacked the town, they killed my younger brother, they killed my uncle, they burned him and his child. We fled to Uba. We were there for five days and were attacked again. We fled for our lives and went to Yola. We left my grandmother there because she wasn’t strong enough to move herself. That was how she died. We were in Yola for two to three months until it was attacked, so we ran for our lives to Jos.

Now I am helping other people with my work. When people go out, go to farm, they are at risk. But if I give them risk education, it will help them to identify it and it will save their lives. We tell them about the dangers and what to do if they encounter bombs. We tell them who to report to and what they should do to protect their lives. We put the safety messages into songs and play games so that they understand the messages. We also gather information on contaminated areas and map the information.

MAG teams of community liaison staff work across the region, usually doing three-week stints, often in difficult conditions. In Bama’s General Hospital camp, the team organizes separate groups of men and women in preparation for life-saving lessons related to explosive ordnance. One of the community liaison officers (CLOs), a young woman called Thlawur, entertains a large and growing group of children. This is the most fun the kids have had in ages, they are ecstatic—totally overexcited. She leads the crowd of kids away from the risk education lessons across to another part of the camp to stop them from disturbing the lessons for the adults. There is little for the kids to do in the camp: no TV, no PlayStation, in fact the only toys you see are homemade, like wire buggies with bottle-top wheels. Thlawur has the kids dancing and singing songs with lines like “What do you do if you find a bomb?”

As I was leaving the camp on my last day in Bama, I saw a distinguished looking man with a smart embroidered hat and shirt. I stopped to take his portrait, and he explained that he was Aga Jato, the Bulama from Kimeri village. He told me everyone had fled three years ago and can never go back because there are improvised landmines on all the tracks. As we were talking, a crowd gathered and different people added their landmine story. One man called Jelomi from Mairamburi village described how he stepped on a mine: “It made a loud bang and metal cut my leg,” he said pointing at a scar running around his left calf muscle, “but the mine didn’t go off properly. It was made from a milk tin and it was the lid that cut my leg.” Jelomi was fortunate—the explosives didn’t go off, and it was probably the force of the detonator that blasted the lid into his leg.

The men described all sorts of things they have seen made into improvised landmines from perfume bottles to cooking pots. They explained that the army cleared the main routes, but roads to small villages and all of the tracks and paths were mined. They said that there was a lot of unexploded shells and bombs as well from all of the fighting that has happened over the years. “More than 300 villages around here are mined!” Umar Modu Saya told me.

In Gwoza, Boko Haram’s former califate capital, the camp chairman of the GSS IDP camp Ibrahim Mbaya explains that two weeks earlier there had been a well-coordinated and intense attack by Boko Haram. The camp was caught in the cross fire of the night-time attack:

Rockets and bullets were flying, we all lay on the ground in fear. We could hear the insurgents calling out “Allahu Akbar”—it was very frightening, and we have all experienced this before. The attacks also mean there are unexploded shells. We are grateful to MAG for helping us learn how to recognize the threat. People find things now and report them to me rather than trying to pick them up.

Teenager Mamma Buji is one of thousands of children taught to stay safe by MAG staff. The lessons use song and puppet shows.

In Bama, people explain to MAG staff where they have seen unexploded devices. This survey work is essential to help keep people safe.

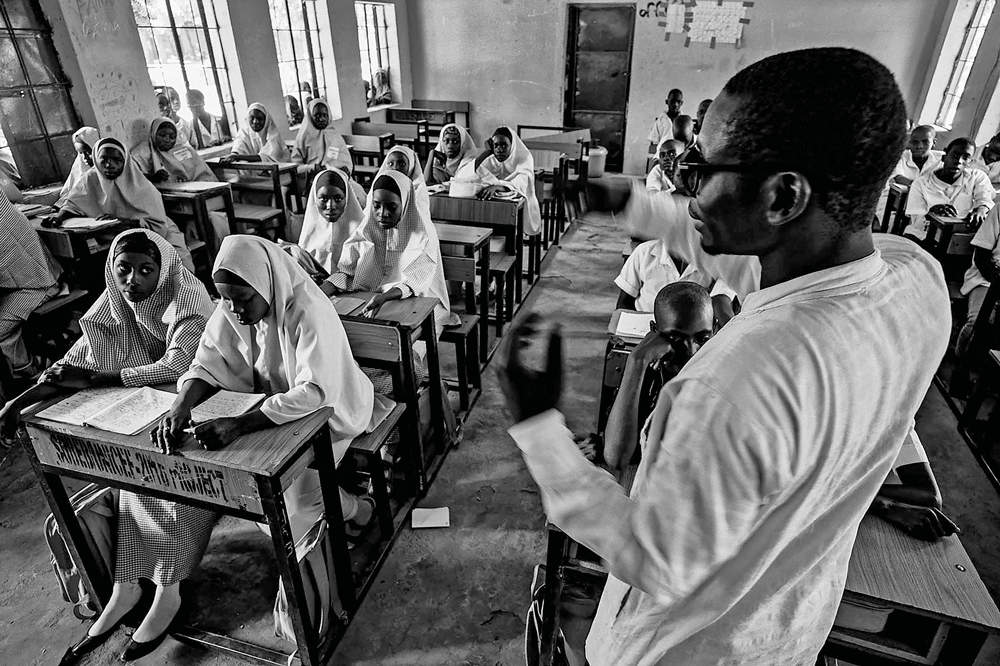

Lessons in Bama camp.

Sean Sutton

Photojournalist and International Communications Manager

MAG (Mines Advisory Group)

Sean Sutton is an award-winning photojournalist; his well-known pictures show the impact of landmines and explosive remnants of war on communities and have been published and exhibited all over the world. His book documenting how unexploded ordnance affects people in Laos was runner-up for the Leica European Publisher’s Award. Sutton is MAG’s international communications manager and has worked for the organization since 1997.

Sean Sutton is an award-winning photojournalist; his well-known pictures show the impact of landmines and explosive remnants of war on communities and have been published and exhibited all over the world. His book documenting how unexploded ordnance affects people in Laos was runner-up for the Leica European Publisher’s Award. Sutton is MAG’s international communications manager and has worked for the organization since 1997.