Innovative Finance for Mine Action

CISR JournalThis article is brought to you by the Center for International Stabilization and Recovery (CISR) from issue 25.2 of The Journal of Conventional Weapons Destruction available on the JMU Scholarly Commons and Issuu.com.

By Camille Wallen [ The HALO Trust ], Peter Nicholas, and Anna von Griesheim [ Social Finance ]

Achieving a world free of landmines will require at least US$1 billion in additional funding. Bridging this gap will require using all available funding sources and maximizing the efficiency of spending. Innovative finance can help achieve both aims by accessing funding not traditionally available for mine action. To explore these options further, the UK government commissioned work to examine the potential roles of innovative finance in mine action. After discussions with a range of stakeholders, a broad consensus emerged around three approaches. First, outcomes finance, whereby funding disburses against independently verified results, such as mine clearance and recovery of activity on cleared land; the focus on results incentivizes effective implementation. Second, outcomes-based public private partnerships, whereby a government transfers land to the private sector conditional on mine clearance, with in some cases the government (or a donor) also subsidizing restoration of productive activity on the land, conditional on achievement of goals such as employment creation. Third, front-loaded funding, whereby donors make long-term pledges of annual funding to mine action; highly rated bonds are then issued to finance more immediate mine action by securitizing the long-term pledges.

It is estimated that there is a US$1 billion shortfall in funding to deliver the 2025 aspiration of a world free of landmines. There is also an imbalance in funding, which limits progress that some mine-affected countries can make towards becoming mine free. The funding gap is likely to increase due to budgetary pressures on traditional donors caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. Though it is challenging, this means that it is even more important that alternative funding mechanisms be developed. Donors and national mine authorities will need to be creative and innovative, and everyone will need to contribute.

Over the past few years there has been plenty of discussion in the broader development community around “alternative development financing.” However this has not been the case in the mine action community. It is worth recalling the Political Declaration agreed to by States Parties in Oslo at the end of 2019: “We will explore options for new and alternative sources of funding with a view to increasing the resources available to realize the Convention’s aims.”1 This commitment is also contained in Action 42 of the Oslo Action Plan.2

With this in mind, the UK Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office brought together a team including Social Finance3 and The HALO Trust4 to look at how innovative finance could accelerate mine clearance while improving its efficiency. The team talked to a range of governments, nongovernment organizations (NGOs), and private sector stakeholders, and found a broad consensus as to the current challenges affecting funding, and how new financing mechanisms could improve funding and incentivize more effective mine action implementation.

Challenges

Six challenges to more effective mine action came up repeatedly in the team’s discussions:

- Inadequate funding for mine action, partly because mine clearance is not always seen as a development need

- Funding structures that do not incentivize efficient implementation of mine action

- Short-term, uncertain funding leading to difficulties in effective planning

- Insufficient data on the benefits of mine action

- Sometimes weak national ownership for mine action and inadequate linkages to broader development planning

- Sub-optimal coordination within and between donor governments.

Making Mine Action More Efficient and Effective

The stakeholder discussions led to the development of innovative financing mechanisms that held strong promise of overcoming these challenges. Once preliminary versions of the mechanisms were ready, they were further developed against the specific challenges faced in representative case study countries—Afghanistan, Angola, and Cambodia—with the invaluable contribution of national mine authorities and other country stakeholders.

Mechanism 1: Outcomes Finance

Traditional grant finance disburses against inputs with payments often not, or only marginally, linked to results. By contrast, outcomes finance disburses against independently verified results, such as mine clearance and recovery of social and economic activity on land cleared of mines and explosive remnants of war (ERW). Outcomes finance could also potentially disburse against victim assistance and risk education, although measuring success may be more difficult.

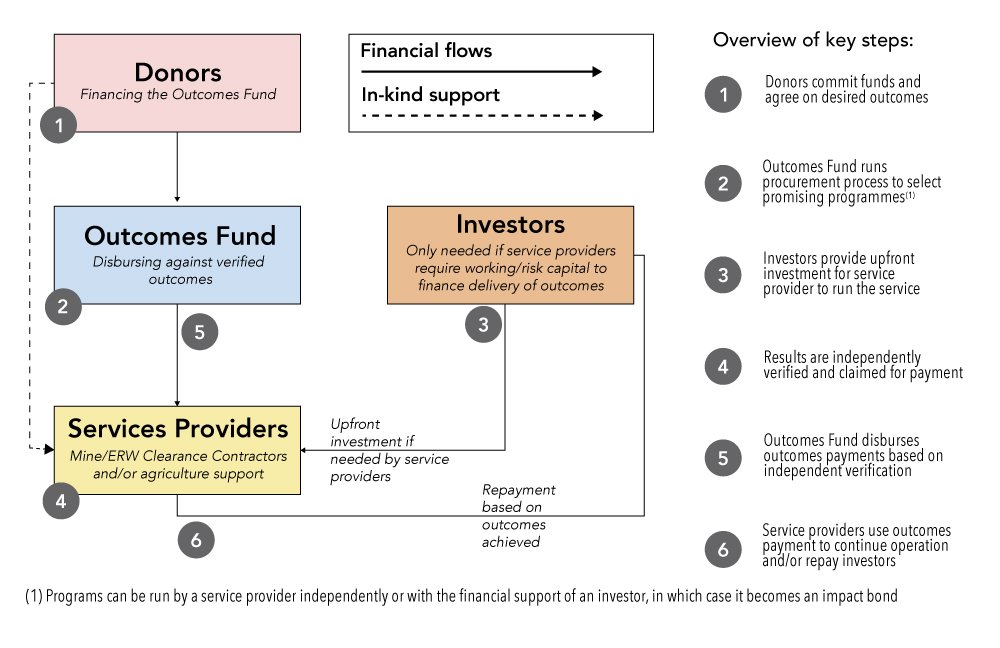

Figure 1. (Example) Outcomes fund for restoration of sustainable agriculture on contaminated land.

What is outcomes finance? By definition, outcomes finance focuses on results rather than means, making it a powerful tool to incentivize flexible, adaptive implementation geared to achieving results rather than following rigid log-frames. It could bring together disparate actors to finance effective and efficient mine action, and hold service providers to account with rigorous and independently verified data on results. The broadest form of outcomes finance is an outcomes fund, which makes pooled funding available for any qualifying program that aims to achieve defined objectives, such as restoration of activity on cleared land. Funds can be made available competitively, so that only the most promising and cost-effective proposals are offered funding against prospective achievement of defined goals.

Outcomes funding pays ex-post, so there is a need for a source of working/risk capital to cover the gap between program funding and payment for the results the program has achieved. This capital can come from service providers themselves, or from an impact bond, which sources external risk capital from a development financial institution (DFI) and social investors, and potentially has additional advantages discussed in Section 2 on paycheck protection programs (PPPs). Investors are attracted to impact bonds by the mix of financial and social returns (paid by the donors/outcomes payers upon successful achievement of outcomes), and the potential to introduce a more dynamic, adaptive, and effective way of managing development programs.

Especially where the capital comes from service providers themselves, there is a need for early payments on outputs. For mine clearance organizations it might make sense for donors to pay them the full costs of the clearance on completion of the outputs, with a bonus (paid by the donor/outcomes payer) when final outcomes are achieved (to encourage collaboration with other actors).

Outcomes finance of any form can coalesce different departments within a single donor behind the common goal of achieving agreed results and can help bring similar cohesion to recipient governments and service providers. It can also play a role in facilitating collaboration between donors behind shared objectives. Greater national ownership is also encouraged by having the progress of national programs measured objectively and publicly.

Making payment conditional on objectively measured mine action results—including broader development benefits—could also help secure new and enlarged donor funding by (a) reassuring donors skeptical of the cost-effectiveness of mine action compared to other development programs (since they only pay on achievement of outcomes), and (b) reassuring donors that the benefits of mine action will be measured with rigorous and independently verified metrics.

Outcomes finance in practice: an example. Results payments in an outcomes finance structure would likely be made against independently evaluated outcomes, for example, restoration of economic and social activity. As illustrated in Figure 1, donors create a pooled outcomes fund that supports both mine clearance and restoration of economic activity on cleared land (in this example, sustainable agriculture).

The fact that there are payments against an end-stage results, in this case restoration of agriculture, motivates mine action and rural development service providers to find ways to work together. This is because some or all payments to both are dependent on achieving a common goal (to make the model workable, mine clearance operatives would receive almost all their funding against achievement of cleared land, with an incentive bonus for ultimate achievement of economic and social objectives). Demining obviously has to precede restoration of farming or livestock, but the work of preparing for that restoration—for example, design of training and provision of agricultural tools and seeds—needs to begin before demining is completed. This is particularly important where beneficiaries include ex-combatants who may have no previous agricultural experience.

Where the political economy allows, an outcomes fund could also work to align interests, facilitate cooperation, and pool funding between neighboring countries to clear border land. This alignment of interests would facilitate mine action planning across a region, in turn helping to increase the effectiveness and efficiencies of the program, and potentially enhancing stabilization.

Benefits of the model. Outcomes finance brings a more flexible and adaptive approach to implementation. With accountability linked to results rather than inputs, service providers have the freedom and the incentive to continuously adapt and improve their implementation, without the need to seek funders’ approval (within fiduciary and safeguard norms). This flexibility is crucial in mine action where the return of land, whether rural or urban, to effective economic and social activity may depend on close collaboration across a broad spectrum of actors, including direct beneficiaries, financial institutions, value chains, extension agents/business development support (BDS) providers, etc.

Outcomes finance also encourages longer planning horizons, bringing more predictability and efficiency to both governments and service providers by guaranteeing finance against completion of a defined task. Indeed, one option in countries close to being mine free is for donors to make payments (or a significant bonus payment) against mine clearance completion nationwide or in a defined region.

Further, outcomes finance also has the potential to strengthen national ownership of mine action; as it can, through the choice of outcomes, be aligned directly with national priorities. Where a broad range of development outcomes are selected, it could also help to catalyze increased collaboration between ministries. Accurate reporting of mine clearance is encouraged by the linkage to subsequent successful use of the land.

Challenges to overcome. Introducing any new finance model incurs challenges that will need to be carefully planned for. These challenges include

- Lack of expertise with innovative financing instruments, including in planning for and managing outcomes-based payments; nonetheless impact bonds have been successfully introduced across a range of sectors in nineteen low- and middle-income countries over the past seven years.5

- Patchy current measurement of mine action outcomes; accurate and on-time reporting of outcomes is one of the central capacity-building elements of any results-based financing instrument.

- Risk that financing becomes the primary focus rather than activities and outcomes, particularly if there are multiple stakeholders; this underlines the need for the payment incentive structure to be carefully aligned with broad mine action goals.

Mechanism 2: Outcomes-Based, Public-Private Partnerships

Any significant return of safe, private sector activity to currently mined land will require subsidies, both for mine clearance itself and also in many cases to support the initial investment in productive economic activity on the cleared land. However, traditional input-based subsidies, especially those to private enterprises, are notorious for misallocating resources and creating perverse incentives. Outcome-based subsidies, on the other hand, directly reward achievement of a defined result, rather than subsidizing inputs that may or may not help achieve that result. An outcomes-based PPP model is designed to support and incentivize both mine clearance and subsequent private sector, for-profit, investment. The foundation of the approach is transfer of land to the private sector, conditional on successful mine clearance, creating the conditions for investment and subsequent socioeconomic development (thanks to Chris Mathias of the British Asian Trust for this suggestion).

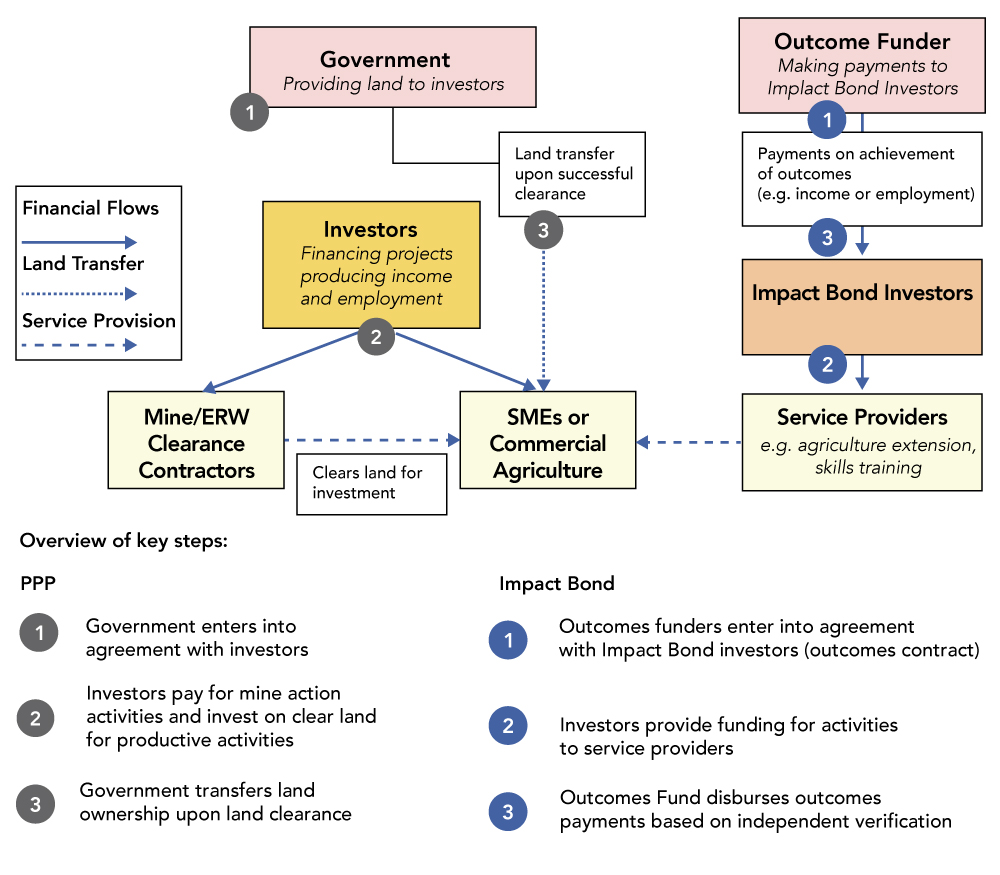

Outcomes-based, public-private partnerships in practice: an example. Specifically, the proposal is that the government commits to transferring ownership of part or all of a plot of contaminated land to a private investor upon successful mine clearance financed by that investor. Where land is highly valuable and contamination relatively easy to clear, the investor might be expected to receive only a portion of the land from the government in return for clearance, paying market price for the remainder. Conversely, where land is less valuable and more expensive to clear, the government may need to forgo any payment from the investor for the land, and pay a portion of the cost of mine clearance as well. This approach is shown on the left-hand side of Figure 2.

The transfer of ownership of cleared land may be incentive enough on its own to foster not only mine clearance but also investment on the demined land. However, in many cases these incentives may not be sufficient to generate investment that contributes meaningfully to government goals of additional employment and income, especially for vulnerable groups.

In such cases where additional temporary subsidies are needed to ensure optimal productive use of the cleared land, additional subsidized support could be provided through services such as agriculture extension, business development services, and skills training for potential employees. The risk with traditional approaches to providing these services is that they have a relatively poor record worldwide of alignment with the real needs of the intended beneficiaries (farmers, small- and medium-sized enterprises [SMEs], potential employees, etc.), and therefore often fail to achieve significant economic or social impact. Outcomes finance, on the other hand, has been shown to support service provision in a way that aligns it more closely with the needs of beneficiaries. This alignment is achieved by rewarding service providers only when agreed end-results in terms of income and employment are achieved, rather than for providing a service whether or not it actually meets the supposed beneficiaries’ needs.

In practice, most service providers experience difficulty in borrowing significant amounts of working/risk capital to bridge the funding gap until (hopefully) payments for outcomes are received. In these circumstances an Impact Bond (shown on the right of Figure 2) is one promising solution.

Benefits of the model. An outcomes-based public-private partnership model shares many of the same benefits as the outcomes finance model noted previously, including potential for greater flexibility and adaptability, enhanced national ownership, and improved predictability and efficiency. Furthermore, an outcomes-

based public-private partnership has the potential to break down siloes between national government entities, donor agencies, and organizations working within and outside of the mine action sector (education or agriculture) by aligning interests and incentives.

Impact bonds rely on external private investors to provide the risk/working capital that service providers often cannot reasonably afford. Relying on experienced external capital has the further advantage of allowing an increased degree of flexibility, adaptation, and prudent risk-taking from service providers, compared to self-financing. Impact bond capital typically comes from development fund institutions (DFIs) and private sector social financiers who hire experienced performance managers who use real-time data to facilitate quick and continuous learning and adaptation to reach the agreed payment metrics. By contrast, where the working capital derives from the service providers themselves, they are often unwilling and/or unable to take the calculated risks of a more flexible and adaptive approach, and are often unable to make the necessary use of real-time data compared to performance managers hired by external investors.

An impact bond for skills training in Palestine provides an example of how this approach can better align service provision with the actual needs of the private sector. In this impact bond, the World Bank is disbursing against (inter alia) trainees securing long-term employment. This has incentivized skills training providers to work closely and proactively with potential employers from the design of the training to the initial apprenticeship. Similarly, conditioning payment for business development service (BDS) and agriculture extension on productivity improvements would incentivize service provision that is much more closely and actively tailored to the real needs of the beneficiaries.

As illustrated in Figure 2, an investor puts in risk/working capital to finance capacity building for the SMEs and their potential employees (for example, BDS and skills training). An outcomes funder provides conditional finance against verified outcomes such as increased employment.

Where feasible, alignment between service providers and investors would be further increased by having a single investor (or investor group) investing in both the impact bond and the mine clearance and SMEs/commercial agriculture.

Challenges to overcome. To ensure that goals and target groups are in line with government priorities, this model would need to be implemented in close coordination with both development and mine clearance entities within the government.

- In addition to the challenges identified previously

- The applications of the PPP model must be carefully designed so that they unlock private funding without compromising national goals and requirements.

- Modalities of the collaboration with private companies will likewise need to be handled sensitively so as to be in line with national aspirations and standards.

- There is a risk of corruption in the land transactions, and transparency will therefore need to be a key element in the model’s application.

Mechanism 3: Front-loading funding

What is front-loading funding? A funding mechanism to front-load finance based on multi-year donor pledges could be used to improve continuity and planning for mine action programs, and also enable longer-term outcomes to be measured. The International Finance Facility for Immunisation (IFFIm) approach could be applied to mine clearance, as it also employs quantifiable, finite results. This model would have a particular benefit in supporting the accelerated completion of mine clearance in a country, region, or other defined geography.

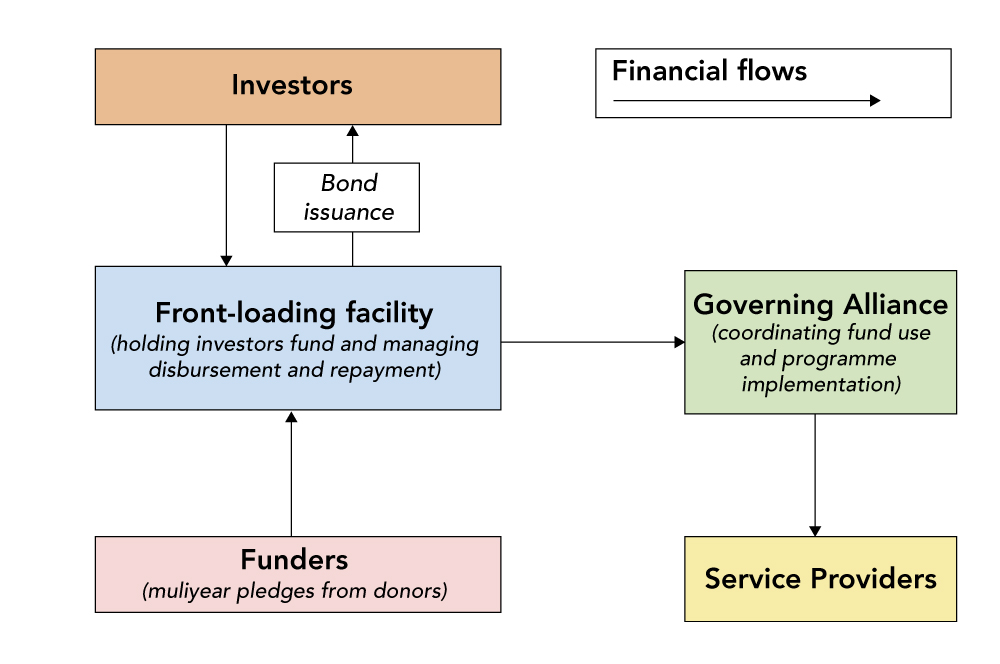

Figure 3. Front-loaded finance model.

Front-loading funding in practice: an example. IFFIm (the model for this analysis) is designed to accelerate disbursement of funds to achieve more rapid dividends, while spreading the cost to donors over a much longer period. In the case of mine action there would be four elements:

- Donor governments make long-term, irrevocable, and legally-binding pledges of annual funding to mine action.

- By using, for example, the World Bank as treasury manager, these long-term pledges support the issuance of highly-rated bonds, allowing the securitization of future pledges, and thus more rapid results on the ground.

- Funds are disbursed for priority mine clearance programs.

The selection of mine clearance programs for funding, and the management of disbursing funds, is governed by an alliance (in the case of IFFIm it is Gavi, The Vaccine Alliance), with a board that brings together key actors including recipient countries, donors, implementing organizations, and UN agencies.

Benefits of front-loading funding. This model brings a number of benefits for donors and recipient countries as it provides accelerated funding to maximize impact and reduce the costs of interventions. The stable, multi-year funding, aligned to national completion plans, facilitates the planning of activities and enhances national ownership by giving beneficiary states a seat at the table. It also delivers on grand bargain objectives.6 It allows for more rapid achievement of humanitarian and economic benefits, thus potentially appealing to donors who do not want to be involved in the long-haul of funding individual mine action programs.

While the same result could be achieved if donors were able to supply all of the required funding upfront, IFFIm has proven that donors are willing to make long-term pledges where immediate funding is not available. The legal and administrative mechanisms for making such legally-binding pledges is already in place for ten donors from their funding for IFFIm.

While there is a small cost to front loading from bond issuance costs and interest on the bond (although this will be low because of the strong sovereign credit rating of likely donors), there are four key benefits:

- significant saving of lives and in preventing of disabilities

- efficiency gains from the economies of scale that can be achieved from faster mine clearance

- administrative cost savings in being able to wind down national mine action agencies earlier

- sovereign bond interest rates, even without any of the benefits noted previously and purely in net present value (NPV) terms, benefit to accelerating the gains from mine action, as the NPV discount rate far exceeds current sovereign bond interest rates

The proposed approach could also attract new funders, who would see immediate benefits without a significant immediate call on aid resources. For some funders there is also the potential attraction that it does not require the added complexity of involvement of the private sector, either as investors in an impact bond or as partners in a PPP.

Challenges to be overcome. IFFIm has major administrative overheads, but it becomes a cost-effective model at a value of about $100 million or more in pledges. A mine clearance fund could bring this threshold down considerably by initially focusing on a small group of countries and a restricted set of donors. In addition, the Mine Action Fund would only finance mine clearance, whereas IFFIm finances fifteen distinct programs. By focusing on one, easily-

measurable objective, the management costs would be greatly reduced. In addition, there is potential for further streamlining by having the fund disburse on an outcomes basis; in that case the Fund would simply pay out against progress towards mine-free status with a bonus on completion. Risk capital could be supplied by an impact bond.

Next Steps

To make these mechanisms a reality that could materially advance mine action globally, they will need to be piloted, potentially in one or more of the countries used as case studies in developing the mechanisms: Afghanistan, Angola, and Cambodia. The team’s full report6 identifies in detail the steps needed to move towards piloting, but the key is to rapidly bring together major stakeholders in pilot countries to start turning these models into transformative reality. ◊

Interested parties are encouraged to contact Joe Shapiro, Mine Action Lead, UK Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office, joe.shapiro@fcdo.gov.uk.

Camille Wallen

Directory of Strategy

The HALO Trust

Camille Wallen leads the development of HALO’s organizational strategy and oversees the functions of European donor relations, policy, and advocacy, and monitoring, evaluation, accountability, and learning. Since joining HALO in 2012 in Sri Lanka, Wallen has worked extensively across programs and partners, all government donors, and HALO USA. She leads HALO’s work on innovative finance and has been exploring various models over the past few years. Wallen holds a Masters from the University of Bath and studies environmental issues and sustainable business models in her spare time.

Camille Wallen leads the development of HALO’s organizational strategy and oversees the functions of European donor relations, policy, and advocacy, and monitoring, evaluation, accountability, and learning. Since joining HALO in 2012 in Sri Lanka, Wallen has worked extensively across programs and partners, all government donors, and HALO USA. She leads HALO’s work on innovative finance and has been exploring various models over the past few years. Wallen holds a Masters from the University of Bath and studies environmental issues and sustainable business models in her spare time.

Peter Nicholas

Director

Social Finance

Peter Nicholas is a Director at Social Finance, involved in developing innovative financing instruments in low- and middle-income countries. His work has included the design of Impact Bonds in the West Bank and Cameroon, outcomes-based Public-Private Partnerships in Mozambique, and outcomes funds for malaria elimination. He has also supported a partnership between philanthropic donors, service providers, and the government in Liberia, as well as helping to develop an Impact Bond to expand kindergarten education in Jordan. Previously Nicholas worked for over twenty-five years at the World Bank as a program manager, based in Washington, D.C., Harare, Luanda, and Thimphu. He has published on the social costs of economic restructuring and on the special needs of small economies. Nicholas holds an M.Phil. in Economics.

Peter Nicholas is a Director at Social Finance, involved in developing innovative financing instruments in low- and middle-income countries. His work has included the design of Impact Bonds in the West Bank and Cameroon, outcomes-based Public-Private Partnerships in Mozambique, and outcomes funds for malaria elimination. He has also supported a partnership between philanthropic donors, service providers, and the government in Liberia, as well as helping to develop an Impact Bond to expand kindergarten education in Jordan. Previously Nicholas worked for over twenty-five years at the World Bank as a program manager, based in Washington, D.C., Harare, Luanda, and Thimphu. He has published on the social costs of economic restructuring and on the special needs of small economies. Nicholas holds an M.Phil. in Economics.

Anna von Griesheim

Analyst

Social Finance

Anna von Grieshheim is an Analyst at Social Finance in the International Team. Since joining Social Finance in 2020, her work has included exploring the potential of innovative finance to fund and enhance landmine clearance and concept testing innovative finance models with mine action stakeholders in mine-affected countries, supporting the implementation of a youth employment DIB in the West Bank, and assessing the suitability of an outcomes-based approach to fund an economic empowerment program for women. Prior to joining Social Finance, von Griesheim graduated from the London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE) with an MSc in Development Management where her research focused on gender issues within vulnerability to climate change in developing countries. As part of her master’s degree, she also did a research project for UN Women on the impact of different financing mechanisms on their work in gender equality. She holds a BA in Economics and Social Entrepreneurship from the University of Southern California (USC).

Anna von Grieshheim is an Analyst at Social Finance in the International Team. Since joining Social Finance in 2020, her work has included exploring the potential of innovative finance to fund and enhance landmine clearance and concept testing innovative finance models with mine action stakeholders in mine-affected countries, supporting the implementation of a youth employment DIB in the West Bank, and assessing the suitability of an outcomes-based approach to fund an economic empowerment program for women. Prior to joining Social Finance, von Griesheim graduated from the London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE) with an MSc in Development Management where her research focused on gender issues within vulnerability to climate change in developing countries. As part of her master’s degree, she also did a research project for UN Women on the impact of different financing mechanisms on their work in gender equality. She holds a BA in Economics and Social Entrepreneurship from the University of Southern California (USC).