Black in America

Arts and Culture

SUMMARY: Awadagin Pratt, an internationally renowned pianist and professor of piano at the College Conservatory of Music at the University of Cincinnati, gave a presentation, "Black in America," as part of the 2022-2023 Madison Vision Series.

Faculty, staff and administrators must be aware of what life looks like for their Black students, as “they're constantly doing battle with feeling threatened by the criminal justice system while under the same pressures to study and produce as students in a manner equal to those without those pressures,” guest speaker Awadagin Pratt said during a Madison Vision Series event Feb. 21.

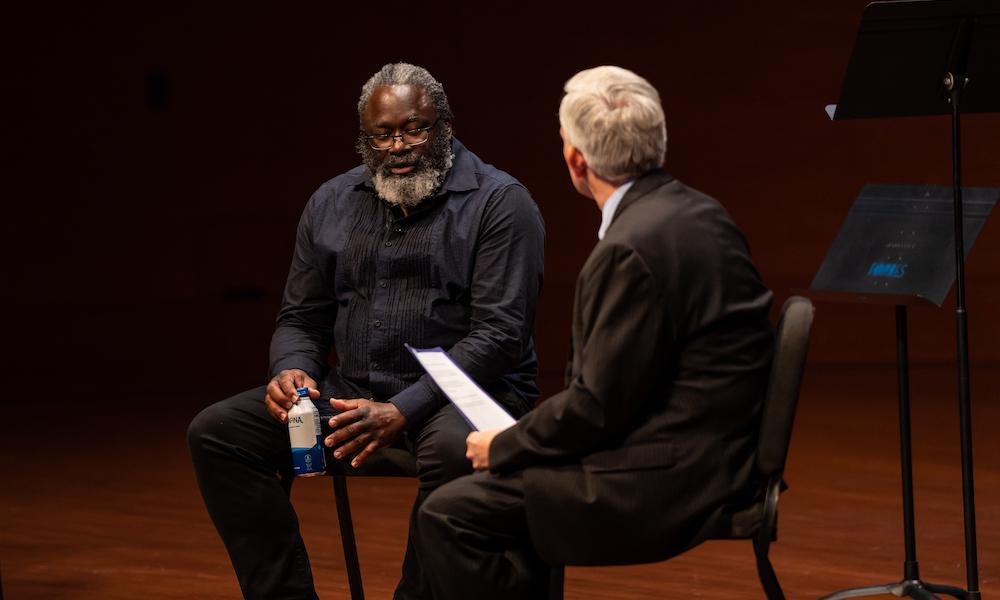

Pratt, an internationally renowned pianist and professor of piano at the College Conservatory of Music at the University of Cincinnati, presented “Black in America” in the Concert Hall of the Forbes Center for the Performing Arts. The presentation included a live musical performance featuring JMU string musicians, a short film that confronts African American representation in the media and Pratt’s own accounts of being stopped by police for no apparent reason. Following the presentation, JMU President Jonathan R. Alger joined Pratt on stage for a Q&A session.

“The stop happens when you've been doing everything right, and somehow the lights that transport you into paralytic fear are flashing behind you,” Pratt said. “Every illegitimate stop is freighted with fear because it's not supposed to be happening.”

America witnessed the murder of George Floyd in 2020, which prompted conversations about how Black people are treated by the criminal justice system. Pratt said public discourse around Floyd’s criminal history bothered him, as it insinuates that victims “deserved to be killed because they put themselves in a compromising position.”

“It subtly presumes and presents that Black people who aren't criminals don't get randomly stopped by police,” he said.

Pratt recalled multiple instances throughout his life when he was stopped by police while driving, walking and at airports and train stations.

“The first time it happened — and I can't tell you how many times it has happened — you think, ‘This is not possible,’” Pratt said. “This is not what I read in the Constitution. This is wrong and it's un-American. And then there's the second stop and the third stop. Will this be for the rest of my life?”

He detailed one stop that led to an overnight arrest when he was a student at the Peabody Conservatory of Music in Baltimore, Maryland. “The dean of the school arranged a meeting with me and the chief of police of Baltimore, who, with no apology or sense of irony, told me that I should be grateful, that they were looking out for my safety,” Pratt said.

Pratt urges everyone to be angered by these incidents. “Do you remember the first time you felt something was unfair? Do you remember the feeling of injustice? Do you remember the anger that you felt, even if just for a moment? Now imagine that every couple of years, every year, every couple of months, every week, every day, something stokes that anger. Another incident, another stop, that anger doesn't go away. It grows and then it bubbles over.”

To become part of the solution, Pratt encouraged the audience to be aware of their own prejudices, have uncomfortable conversations with people with whom you may disagree, and show empathy.

“There's never been a golden age to be Black in America. Will you be a part in making that happen?” he asked.

“If the golden age comes for African Americans,” he said, “then it will truly be a golden age for all of America. All will rise.”