Documenting the achievement gap

Education

SUMMARY: Steve James' (’77) latest documentary, "America to me," offers a yearlong look inside one of Chicago's most progressive public high schools.

from the Winter 2019 issue of Madison

In America to me (2018), a documentary about inequality in education by filmmaker Steve James (’77), an exasperated black student at Oak Park and River Forest High School in suburban Chicago blurts out: “Everything is made for white kids, because this school was made for white kids, because this country was made for white kids.”

The 10-part television series, which premiered in August on the Starz cable network, offers a yearlong look inside one of Chicago’s most progressive public high schools.

The project was inspired, in part, by James’ children’s experience in the school system. “One of our kids was a high-performing student and another, despite being bright, was struggling with a learning disability,” he says. “My wife and I saw what a different experience it was for one kid versus the other.”

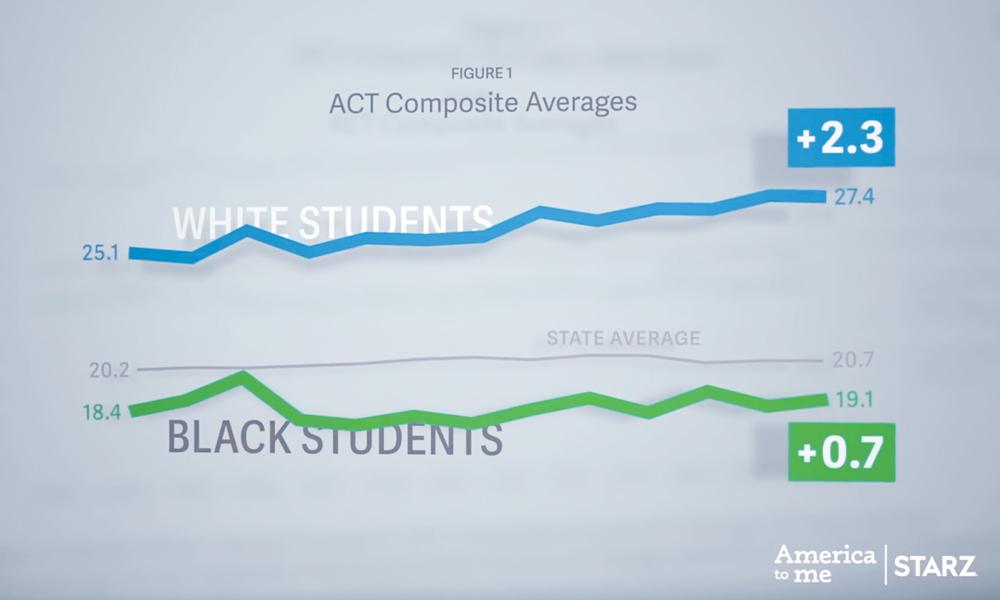

At the time, the Oak Park community was wringing its collective hands over the disparities in achievement between white and black students, James says, and it dawned on him, “How much more difficult would it be for our struggling kid if he were black?”

|

|

To James, director of the Oscar-nominated Hoop Dreams (1994), at least two characteristics of the K-12 public education system contribute to the achievement gap: expectations and tracking.

James advocates for raising expectations, particularly among teachers, of students of color. And he supports alternatives to tracking, the practice of grouping what tend to be overwhelmingly white students in honors and advanced-placement classes while keeping children of color on lesser tracks.

“For all the good intentions, students of different races find themselves on different tracks, in different classes, with different outcomes, in a school that one teacher says ‘functions as two schools in one,’” the New York Times said in its review of America to me. The documentary, it said, “is ample evidence that, in fact, what happened keeps happening—even if it happens in more subtle ways, with coded language and among people who talk the talk of inclusion. It’s an invaluable look at where inequity begins, as well as the difficulty of getting to the place where it ends.”

While making America to Me, James says he learned that reduced expectations based on race are pervasive in education.

“It really does start early for black kids, in particular, and I think black boys even more so—that teachers just have lower expectations of achievement,” he says.

When an African-American student scores a C on a test or in a class, “the parents may be unhappy with it, but the teacher seems OK with it,” James says. “The teacher has made this determination that that’s a good grade for that kid.”

|

Some black families might be inclined to keep their children in lower tracks because they’re performing well there, James adds. Such encouragement from teachers “may come from a place of concern and wanting to be supportive,” he says, “but what it’s communicating is, ‘You are not capable of doing better. This is where you belong.’”

James also sees only putting certain kids in high-achievement tracks—where they take classes that can earn them college credit and grade-point averages above 4.0—as harmful.

“The way in which we define achievement is fraught with race and privilege,” James says. “ACT scores and GPAs are a foundation for how we define whether someone is a good student or not, or a smart student or not. And it’s an incredibly limiting way to define someone’s intelligence.”

James believes the responsibility for effecting change falls on white parents—even if they perceive tracking as beneficial to their own kids. “Real change to the educational system can’t really happen until white people—for whom the system has worked remarkably well over the years—decide that they want to see it differently,” he says.

“I think there’s this feeling that if you do away with tracking, then high-performing kids will be in classes with lower-performing kids, and they won’t get challenged because the curriculum will be built to serve the lower-performing kids, and that will be bad for the higher-performing kids,” James says.

But that doesn’t have to be the case, he says. Research shows that mixing kids raises the expectations and the performance of lower-performing students without hurting the higher-performing ones.

From JMU to the Windy City

James’ passion for filmmaking was sparked at JMU, where, as a communication arts major, he took a film appreciation class in the English department. “I liked movies, and students said that the class was fun and thought-provoking. We watched and discussed the works of great filmmakers—Ernst Lubitsch, Alfred Hitchcock, Jean Renoir and Arthur Penn. I was hooked.”

|

JMU is also where James met his future wife, Judy Roth (’77). After graduation, he followed her to Southern Illinois University, where he studied film and earned a master’s degree.

His breakthrough film, Hoop Dreams, which follows two inner-city Chicago boys’ struggle to become professional basketball players, won nearly every major critical award and established James as a major player on the documentary scene. For his next project, Stevie (2002), James returned to Southern Illinois to reconnect with a boy he mentored 10 years earlier as a Big Brother.

Other film credits include The Interrupters (2011), about three former Chicago gang members who try to protect their communities from the violence they once employed; Life Itself (2014), which chronicles the life and career of renowned Chicago Sun-Times film critic and social commentator Roger Ebert; and Abacus: Small Enough to Jail (2016), which profiles the only company to be criminally indicted in the wake of the 2008 mortgage crisis.

James is a 1994 recipient of the Ronald E. Carrier Alumni Achievement Award.