Restoring humanity at Montpelier

Nation and World

SUMMARY: A new exhibit at James Madison's Montpelier estate addresses the implications of slavery and encourages a broader discussion of race in society.

From the Spring/Summer 2018 print issue of Madison

By Abby Church

Creaking open the rounded, off-white door to the cellar at Montpelier, guests are met with a cool rush of air. Inside, past the pamphlets and listening stations, gray etchings on the walls reveal the names of those who were once enslaved at James and Dolley Madison's estate in Orange County, Virginia.

As visitors trace the names and learn their stories, these individuals start to come alive.

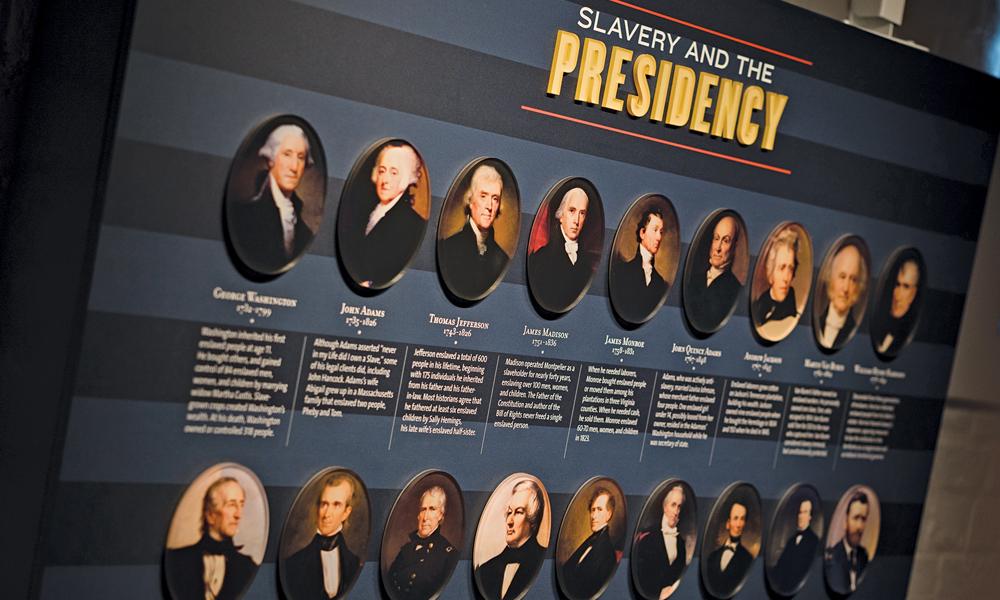

From 1723 until Dolley Madison sold the property in 1844, 320 people lived at Montpelier. Of those, 300 were African-American slaves, encompassing six generations. These were the people who heard the ideals of freedom exalted within the walls of the mansion, yet didn't have it themselves; and the people whose owner, a Founding Father and the nation's fourth president, crafted the document in which freedom was supposedly defined for all Americans.

|

Through its new exhibit, "The Mere Distinction of Colour," the Montpelier Foundation is restoring the humanity of a forgotten community. What makes the project stand out, however, is that the people who helped with the excavation and creation are themselves descendants of slaves.

It's important to understand how Montpelier defines the term "descendant." Starting in the early 2000s, the foundation invited all African-Americans who felt a connection with the history and story it was telling to be part of the descendant community. More often than not, slave families weren't confined to one plantation because of buying and trading. This left families torn apart and documentation of slave family records practically nonexistent. In fact, oral histories from descendants have proven to be more ripe than official records.

"Because of the boundary consideration and also the fact that there's just not that many documentary records, it came upon us to not be exclusive in that sense and allow folks who are connected to this history to connect to the story and be involved in what we're doing," says Price Thomas, former director of marketing and communications at Montpelier.

One of the many descendants who came to help with the exhibition was Leontyne Clay Peck, an author and teacher of African-American history and culture. Having spent most of her adult life in Washington, D.C., Peck and her family relocated to Charlottesville, Virginia, 15 years ago. Not long after she arrived, her grandmother, Laura Price Clay, died and Peck was asked to write her obituary. Assuming that her grandmother was born and raised in West Virginia, Peck asked if that fact was correct. To her surprise, she was told that her grandparents were actually born in Madison County, Virginia.

|

Soon, Peck found herself driving to Madison County to uncover more of her family's history. There, the courthouse clerk pulled a document revealing that Peck's great-grandparents, Amanda and Washington Clay, were freed slaves. "Once she gave me that document, I found the names of my great-great-grandparents—and my great-great-grandfather's name was Henry Clay," Peck says. Peck went on to become involved with the University and Community Action for Racial Equity at the University of Virginia, where she met Matthew Reeves, director of archaeology and landscape restoration at Montpelier.

After turning down Reeves' initial offer to participate in the excavation of the slave quarters, Peck reconsidered. She arrived with an open mind and was assigned to a digging team.

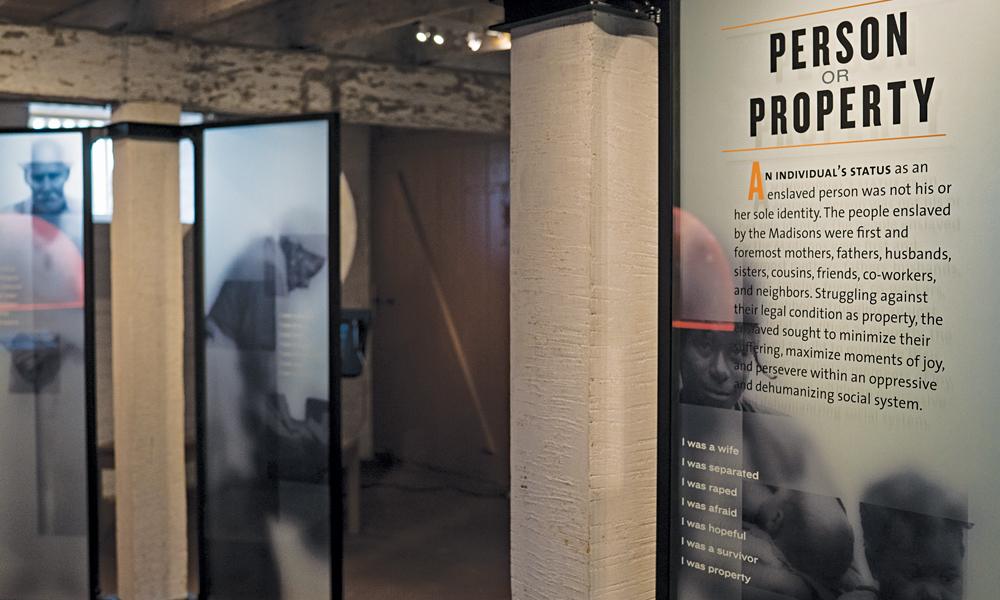

Digging at the grounds where her ancestors may have lived proved to be a surreal and emotional experience for Peck. "It made it a spiritual journey. I felt that with every object that I found [in the South Yard] … I was touching and connecting to that last person who was there. It didn't have to be my relative—it probably wasn't my relative, we don't know—but what I do know is that I felt like they were saying, 'Thank you for coming and sharing our story.'" Christian Cotz ('97), director of education and visitor engagement at Montpelier, explains that instead of focusing on stories of forced labor and poor living conditions, the exhibit presents the slaves as people.

|

"You're never going to know what it would feel like to plow five acres in a day with a mule," Cotz says. "But you can imagine what it might feel like to have your mother taken away from you. You can imagine what that feeling of loss and the inability to do anything about it, the futility of trying to do something about it."

"The Mere Distinction of Colour" is important in addressing the implications of slavery and encouraging a broader discussion of race in society. Peck says these are discussions that we, as a nation, need to be having. "We're still dealing with these issues … with people's humanity," she says. "What happened in [the past] has a direct impact on how we think, how we look at things today." In the "Lives of the Enslaved" section of the exhibit, a board sits in the middle of one of the rooms with "Leave Your Voice" written across the top and pencils and note cards arranged at the bottom. Among the many submissions from visitors is a card from an 11-year-old named Ava. "We should always remember that not everything about us is different," Ava wrote. "There is one thing about us that is the same. We are all people."