Sweeping for clues

Professor and student search for evidence of slave cemeteries at Montpelier

Nation and World

SUMMARY: Shane McGary and Michelle Proulx are using ground-penetrating radar technology to detect possible African-American burial sites at the estate of James and Dolley Madison in Orange County, Virginia, which in recent years has begun telling a more complete story.

from the Spring-Summer 2018 issue of Madison

By Jim Heffernan (’96, ‘17M)

While collecting oral histories for a new exhibit honoring the contributions of African-Americans enslaved at Montpelier, officials heard stories of human bones and other remains turning up in a field near a path a few hundred yards from the main house.

Resident archaeologist Matthew Reeves began to wonder if the site, located across the road from a wooded area with a few modest headstones, was in fact a second slave cemetery on the property. After digging into the matter on his own, he turned to Shane McGary, a noted geophysicist and professor of geology and environmental science at JMU.

“Our work is trying to get a sense of whether there are burials there, where exactly they might be, and helping [Montpelier] better understand the history of the place,” McGary says.

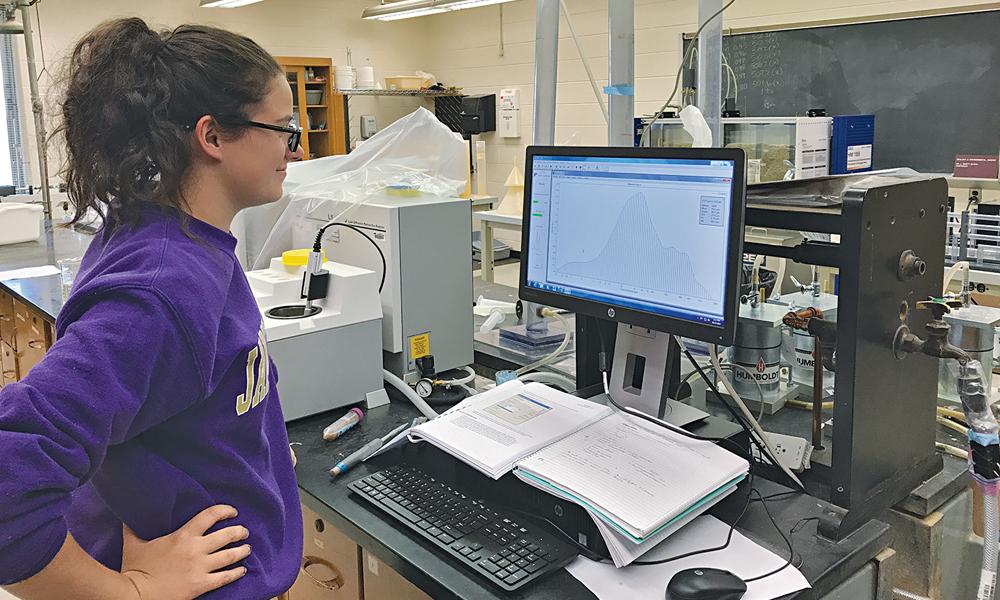

For this important undertaking, McGary enlisted the help of Michelle Proulx, a senior geology major with whom he had worked at other area historical sites with oral histories of slave burial grounds. One of those sites was Belle Grove Plantation near Middletown, Virginia, the ancestral home of the Hite family, including Nelly Madison Hite, sister of James Madison.

“I have always had a great respect for African-American cemeteries,” says Proulx, who discovered the one at Montpelier during a tour her freshman year. “Coming back and figuring out that we could actually do some really great work there and the work would go toward a really good cause has been amazing. I jumped on the opportunity right away.”

|

McGary and Proulx are using ground-penetrating radar technology to sweep for clues. Their cart has a transmitter that sends 400-megahertz electromagnetic pulses deep into the earth. “When it encounters something that has a different set of electrical properties, some of that energy gets reflected back up and picked up by the receiver,” McGary explains. “We’re able to measure the travel times, which tells us something about the depth and distance. And we can also see the intensity, the contrast and electromagnetic properties.”

For different reasons, McGary says, bodies during that time period were often buried east to west—one of the stories that has been told is that slaves were buried with their feet facing east so that they could rise up and walk back to Africa—so he and Proulx look for three consecutive lines running in that direction as evidence of a possible burial plot.

If they were fortunate, slaves families at Montpelier wanting to bury one of their own may have been given some wood by the Madison family for a casket, Proulx says. If not, they would be forced to use whatever materials were available to them.

|

The irony of James Madison, Father of the Constitution and our nation’s fourth president, holed up in his library at Montpelier conceiving of a representative democracy that protects individual freedoms while his slaves kept the home fires burning is not lost on the Montpelier Foundation, which in recent years has begun telling a more complete story of the estate.

“A lot of these historical sites are starting to realize that they haven’t handled the slave narrative very well,” McGary says. “Montpelier has been one of the places at the forefront of changing that.”

In the fall, while working on site, McGary and Proulx met some of the slave descendants whom Montpelier had invited to help with its new “The Mere Distinction of Colour” exhibit.

“We got to show them what we’re doing and how we’re doing it,” Proulx says. “I think they genuinely appreciated our work and really took it to heart.”

For McGary, the project offers a rare opportunity for a geophysicist to be involved in restoring the humanity of a forgotten community. “It’s been really gratifying to realize that something I felt was important is important to a lot of other people too.”