A game changer?

JMU researcher gets new grant to work on Florida python problem

Science and Technology

SUMMARY: One of the toughest challenges in managing the python population, even though it's large, is finding them.

A plan on paper can look like a winner, but until it's executed, it's hard to tell, especially when it involves working with snakes in the wild.

That's the position in which Rocky Parker finds himself as he tries to help a number of federal and state agencies manage a Burmese python scourge in the Florida Everglades.

Ever since pythons got loose in Florida in the 1990s, they have become an ecological nightmare, specifically in the Everglades. Pythons, like all snakes, will eat anything they can get their mouths around, from fish to birds to rodents. And since they have no native predators in their invasive range, they’re free to eat and reproduce at will.

Over the years, the giant snakes — which can grow to more than 20 feet and weigh more than 200 pounds — have altered the ecology of the Everglades, primarily by consuming native mammals and birds, costing the state not only indigenous species, but millions of dollars. Wildlife officials have tried all sorts of ways to trap and control the snakes with varying degrees of success.

With a new $73,000 grant from the U.S. Geological Survey, Parker, a chemical ecologist, says he is taking a slightly new approach to his research, which could significantly improve how wildlife managers find the elusive predators.

One of the toughest challenges in managing the python population, even though it's large, is finding them. "Tracking free-ranging animals is difficult in the Everglades. It's a very impenetrable environment, it's gnarly," Parker said. In addition to that, pythons' skin colors and markings offer perfect camouflage.

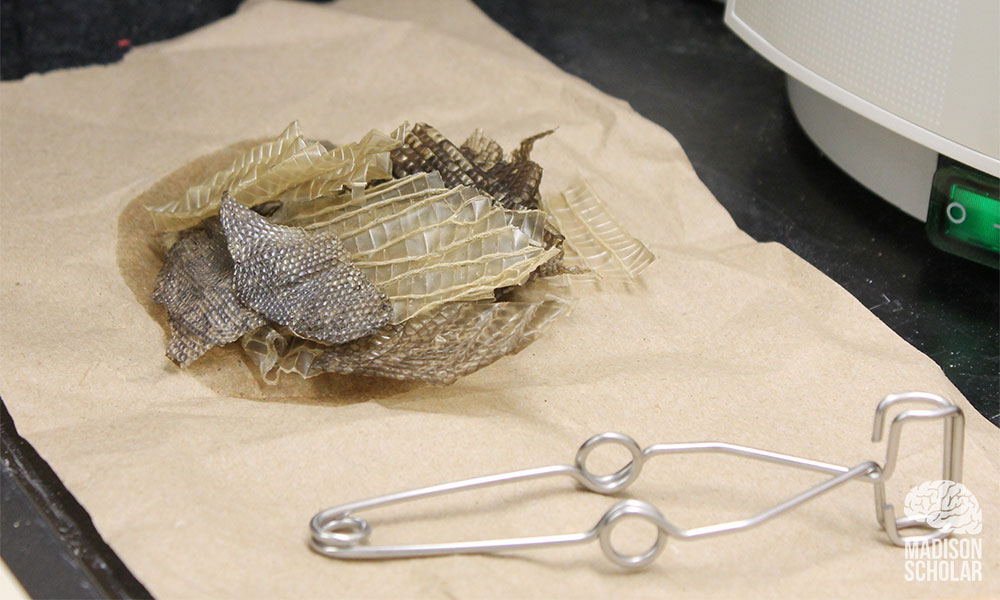

Last year, Parker and his students ran experiments to gauge python reaction to male and female scents. Results of that research, which continues, look promising as male snakes were able to follow female scents and did not follow male scents.

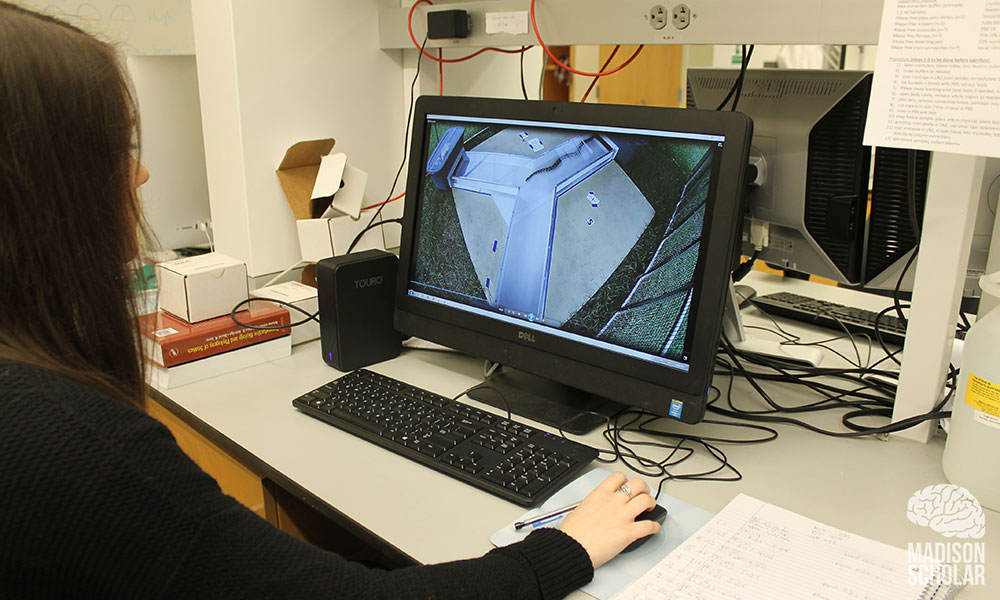

Now Parker wants to combine what he's learned about potentially luring snakes by scent with another technique, called the "Judas" approach. The Judas approach involves tagging individual snakes with transmitters and tracking them, hopefully to more snakes, when the animals are breeding in aggregations. Parker's plan is to make male snakes smell like female snakes, then tag them and set them loose. If it works, the male snakes that smell like females will attract other males and increase the number of snakes that can be trapped.

"I think it's promising," Parker said. "Anything that increases detectability is a very useful tool and if we can make males attractive and make other males come out of their hiding, that could crack this detectability issue, or at least help it."

Parker will make male snakes smell like females by implanting estrogen, a hormone that will trigger female pheromone production, even in males. The technique has worked in garter snakes and brown tree snakes, so it should work in pythons, Parker said. To test its effectiveness with pythons, a control group will be tagged but not given estrogen.

If the results are good, Parker said the approach could be used with other invasive species because hormones such as estrogen and testosterone are the same compounds in just about all vertebrate species.

The project will begin soon with Parker's colleagues from the USGS collecting pythons. The snakes will be tracked during the mating season, which in Florida appears to be between February and May.