Unraveling mysteries of the brain

Undergraduates involved in research funded by NIH

Science and Technology

SUMMARY: The grant, awarded in April to Dr. Mark Gabriele (center), a professor of biology, and Dr. Lincoln Gray, a professor of communication sciences and disorders, will fund the research through March 2020.

It's much too early to say whether their research will someday lead to better treatments for people who suffer from sensory processing disorders such as ringing in the ears, but two undergraduates are happy to be getting the laboratory experience this summer and seeing where it leads.

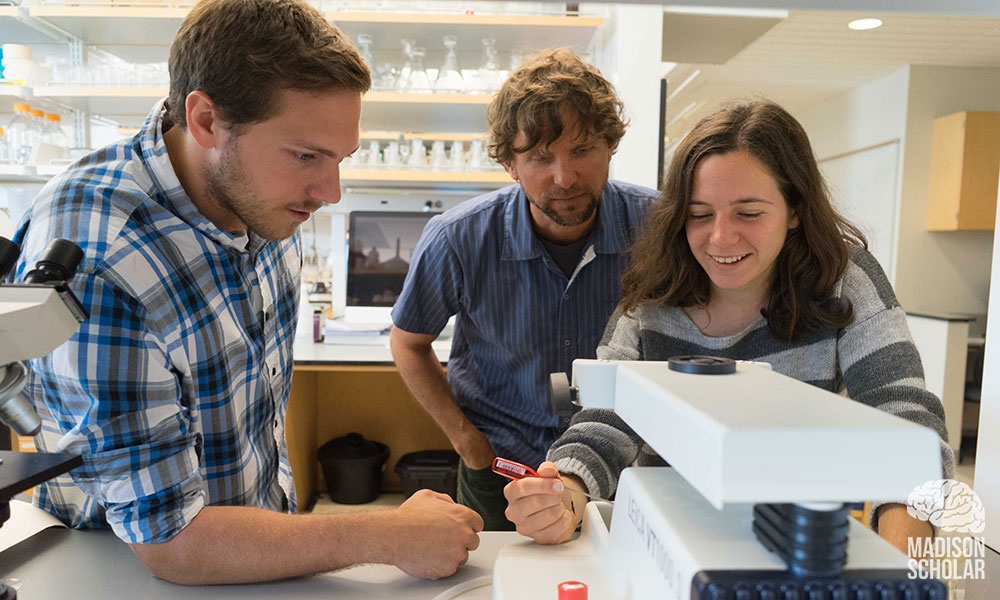

Sean Gay, who graduated with a degree in biology on May 5, and Isabel Lamb-Echegaray, a senior majoring in biology, say it's exciting to be getting in on the ground floor of research that has potential to help people.

The National Institutes of Health is excited as well, to the tune of $427,773.

The grant, awarded in April to Dr. Mark Gabriele, a professor of biology, and Dr. Lincoln Gray, a professor of communication sciences and disorders, will fund the research through March 2020, and comes on the heals of a $320,000 NIH grant they received in 2012 to do research in a related part of the brain.

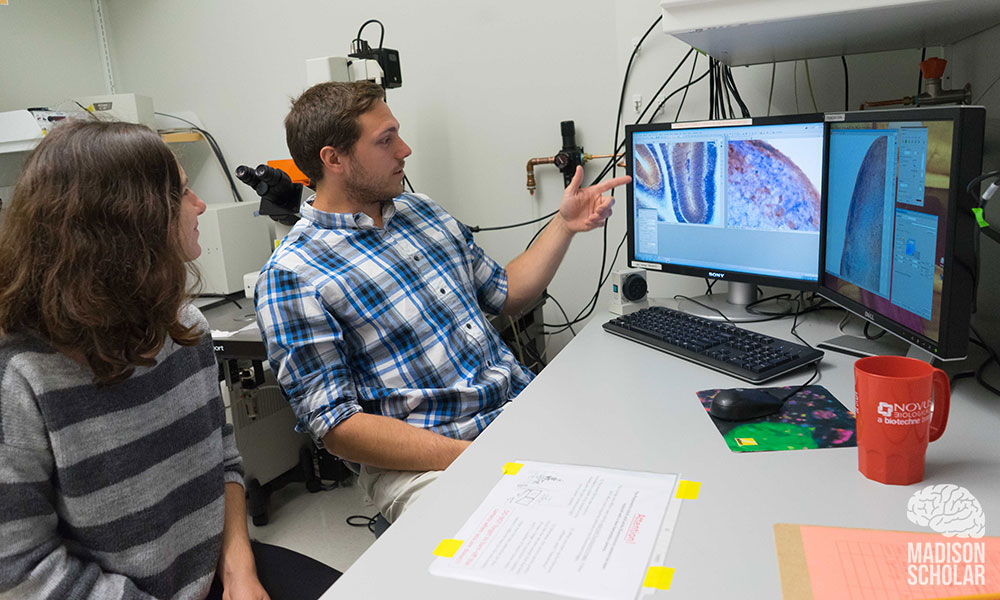

Gabriele said the 2012 grant involved study of a midbrain structure, the inferior colliculus, and a subregion that processes sound. The new grant is funding research in an adjacent area of the inferior colliculus that processes touch and visual cues in addition to auditory information. And unlike the focus of the earlier research, where much is already known, very little is known about this neighboring multisensory center.

"This is what was most exciting to me in writing the grant," Gabriele said. "I was learning as I was going. This was the first grant where I got interested in an area that I knew little about and had to really school myself."

The NIH is interested because the research could help understand some underlying causes for sensory processing disorders such as tinnitus, commonly called ringing in the ears, and eventually lead to better interventions that are noninvasive and available to a larger population than what is now available.

"There are millions of Americans who suffer from hearing disorders, and then when you bring in somatosensation and pain, chronic pain, phantom limb, that number escalates," Gabriele said. "There is a lot of cutting edge neuroscience in these areas, but many interventions involve intricate preparations that are highly invasive, leaving only a small fraction of the people who suffer from these disorders who actually benefit from them."

There is some evidence, Gabriele said, that sensory processing disorders may be caused in part due to negative brain adaptation or plasticity. For many tinnitus sufferers, including military veterans exposed to blasts, the symptoms begin after they have been exposed to damaging sound levels. Such exposure can cause unwanted changes in brain circuitry and thus Gabriele hopes to find ways to train the brain to go back to its original configuration.

Gabriele said Gray's part of the research involves physiological and behavioral testing of the neural circuits of interest and their specific roles in processing multisensory information. The work will involve undergraduate and graduate students in communication sciences and disorders and is concentrated in year three of the grant.

Gay, who has worked in Gabriele's lab the past three years, plans to stick with the project through next school year and then apply to graduate school to pursue a doctorate. "In the past year I have been learning all the techniques so now I can use those and get some good research done," he said. Gay said he is interested in both neurology and immunology.

Lamb-Echegaray says she will likely pursue a career in research after doing a stint with the Peace Corps following her graduation next year. Her role in the current research is looking for relationships between the processing of touch and the processing of sound. Many tinnitus sufferers have said they can ease their symptoms by moving various parts of their body. "It's interesting that it's a part of the brain that no one knows much about," she said. "You have auditory and somatosensory together and why is that?"