Face processing study could contribute to future autism research

JMU senior to present work at spring conferences

Health and Behavior

SUMMARY: Takahashi is working alongside Dr. Krisztina Jakobsen, associate professor of psychology, to explore the development of an own-species bias for face processing.

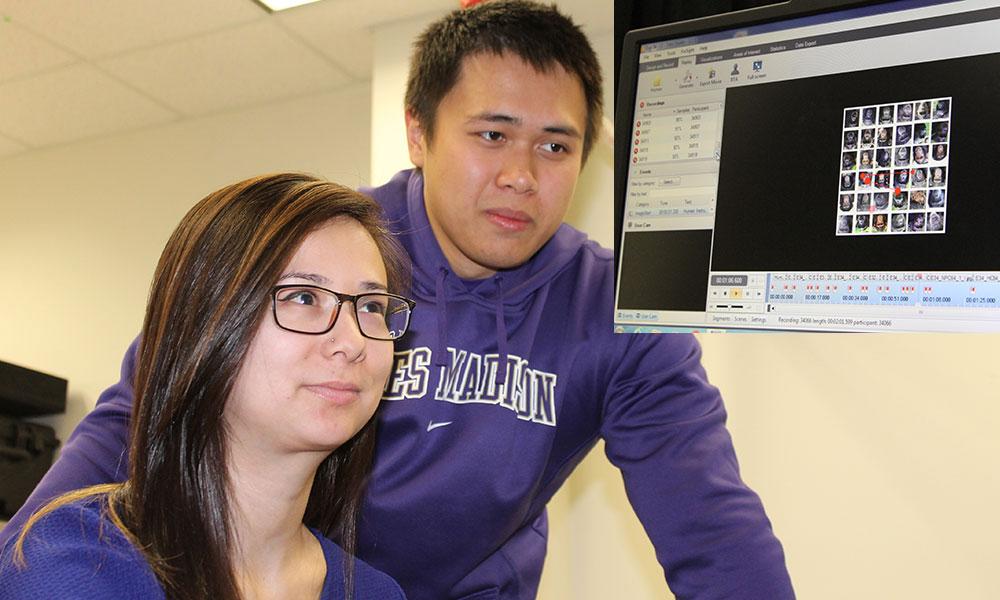

Using cutting edge eye-tracking technology, the cognitive development lab at JMU is working on a study to examine face processing during the first year of life that could contribute to future research that explores early signs of autism spectrum disorder.

The eye-tracking technology triangulates a subject's eyes with cameras and follows them throughout the screen to see where their eyes are drawn first. Eye tracking technology has proven to be useful in testing preverbal infants.

"When we play back the experiment that you did, we can see exactly where you were looking, how long you were looking there and follow your patterns," said Lily Takahashi, a senior psychology major and the lab manager from Centreville, Virginia.

Takahashi decided as a sophomore that she wanted to go to graduate school and looked into gaining research experience.

"I reached out to a couple professors, and the cognitive development lab was one of the most interesting ones I looked at," she said.

Takahashi is working alongside Dr. Krisztina Jakobsen, associate professor of psychology, to explore the development of an own-species bias for face processing. By 6 months of age, infants’ attention is drawn to human faces more quickly than it is drawn to animal faces. Data collected in collaboration with Dr. Elizabeth Simpson (University of Miami) with infant macaque monkeys suggests that as early as 3 weeks of age, macaques detect faces more quickly compared to objects, and by 3 months of age, they prefer to look at macaque faces compared to faces of other species.

The lab is excited to have a new eye-tracker. One thing it is still looking for is a bigger and more diverse population of research participants to obtain more concrete findings.

"Because our research adds to the existing literature and suggests that infants process human faces differently compared to animal faces, others who study infants at risk for autism could use tasks similar to ours to possibly identify kids who might show signs of ASD. As we know, early intervention is key," Jakobsen said.

Takahashi explained that there might be a difference in what facial features babies pay attention to (nose, mouth, and eyes) when they're at risk for autism spectrum disorder. "Children on the autism spectrum may tend to not look at a face's eyes," she said. "So when an at-risk infant (at-risk means they have an older sibling who is on the autism spectrum) tends to not look at a face's eyes, that could be an early indicator that they may not be a typically developing child."

Takahashi will be giving a talk on the research at the Colonial Academic Alliance Undergraduate Research Conference at The College of William & Mary from April 15-17. She also will present her research at the Virginia Psychological Association conference in Norfolk from April 21-22.

"It is extremely beneficial to have experience in a research lab if you are applying to graduate schools that have an emphasis on research because that experience makes you stand out from other candidates," said Takahashi, who has been accepted into the master's program at Marymount University in Arlington to study forensic and legal psychology.

JMU's Cognitive Development Lab is looking for infants under 11 months and children under 4 years old to participate in the studies. Contact jakobskv@jmu.edu if interested.

By Rachel Petty ('17), Communications & Marketing