Q and A with Alan Levinovitz, author of 'The Gluten Lie'

NewsSUMMARY: Before heading to the popular SXSW marketing conference, where he will participate in a March 13 panel discussion titled "Eat This Panel (If You Dare): Food Myths Debunked", Levinovitz talked with us about "The Gluten Lie" and America's fascination with food and health.

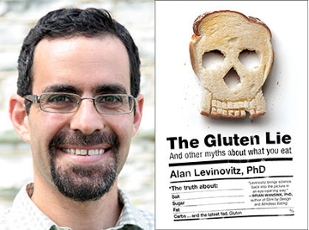

Dr. Alan Levinovitz, assistant professor of religion at James Madison University, exposes the myths behind how we come to believe which foods are good and bad in his book, “The Gluten Lie: And Other Myths About What You Eat.”

Dr. Alan Levinovitz, assistant professor of religion at James Madison University, exposes the myths behind how we come to believe which foods are good and bad in his book, “The Gluten Lie: And Other Myths About What You Eat.”

Before heading to the popular SXSW marketing conference, where he will participate in a March 13 panel discussion titled “Eat This Panel (If You Dare): Food Myths Debunked,” Levinovitz talked with us about “The Gluten Lie” and America’s fascination with food and health.

Q: What sparked the beginning of the gluten-free movement?

A: That actually depends on the population you’re talking about. With the discovery of Celiac (abdominal cavity) Disease, and that people were sensitive to gluten, and that fully removing gluten from the diet helped with celiac, that made removing gluten essential to people with celiac.

Celiac remained undiagnosed for a long time, especially after World War II. On the heels of the Atkins diet, which blamed carbohydrates for a lot of things, a lot of undiagnosed people with celiac began to remove gluten from their diets as a possible solution, and also a possible means of losing weight. Because many things that contain gluten are also things that contain carbohydrates, it made sense that people transitioned from the Atkins diet to gluten-free diets.

Then when celebrities began endorsing this movement, which happened in the early 2000s, gluten-free really started to take off. That was bolstered by the Paleo diet, which rejected gluten as something we were not evolved to eat. A lot of factors were coming together; the idea that we were not evolved to eat gluten, the idea that carbohydrates made us fat and the idea that carbohydrates contain gluten really made gluten-free a powerful movement.

Q: You’re a professor religion here at JMU. What made you interested in writing about debunking food myths?

A: Religious vocabulary infuses a lot of our dietary lives. People talk about eating clean or eating pure. People talk about eating natural foods versus artificial foods. They talk about sinful pleasures – or guilty treats. “Sin” and “guilt” are words coming out of religion. We’re also familiar with dietary taboos from many different religions: kosher in Judaism, halal in Islam and people giving up food for lent in Catholicism. In Chinese religion, which is my teaching area at JMU, there were also dietary restrictions. Daoist monks, nearly 2,000 years ago, advocated for eliminating grains from your diet as a way of clearing up your skin, achieving immortality and never becoming sick.

It’s all the same idea that we can take a staple in our diet, eliminate it and solve all the problems in our lives. These ideas inform people’s choices about what they eat in a religious – not scientific – way that they might not even realize. We end up papering over our desire to remain pure with science. We talk about which foods are natural, and “natural” itself is not a scientific term; there’s not a study to see how “natural” something is because that’s a religious and philosophical category. I wanted to see how those categories shape the way we talk about food. If you talk to someone about their food preferences, it can sometimes be touchier than religion.

Q: Do you find that there’s been an issue with people who decide to self-diagnose?

A: Well, imagine you have celiac disease, but you don’t know it and you’ve never heard of it because you’re just a person who’s sick. You go to your doctor and they tell you, “Eh, just get over it,” so you hear about this gluten-free movement and decide to try it. All of sudden, it’s literally a miracle; gluten-free has saved your life. It actually has saved your life, the science says you did save your life. So you become an evangelist for gluten-free and you tell people, “Hey, are you feeling sick? I went gluten-free and I feel amazing!” That’s a very real thing that happens, and it’s a very powerful force. Something studies have shown is that when you’re trying to identify people who don’t have celiac, but are still sensitive to gluten, those people, over 50 percent of the time, react equally to a placebo as to gluten.

Whatever is going on with gluten, lots of people diagnose themselves too quickly. But that’s not something people want to hear, because that means you’re wrong about yourself, your body and your suffering. It makes you feel stupid and weak, but the truth is that you’re neither stupid nor weak; you’re just a human being. There are many times when self-diagnosis is effective and miraculous, so I understand where people are coming from. I just want people to be aware of the pitfalls of self-diagnosis and the ways in which popular understandings of diet can skew people’s perceptions of what the science does and doesn’t say.

Q: Do diets differ from health weight management? Or do you find they overlap?

A: Healthy weight management, for me, involved thinking holistically. It’s mental and physical. It’s not just a number on a scale or how you’re feeling. It’s about friends, family and culture. I don’t think it’s healthy to have foods completely prohibited. It makes it difficult to go out to dinner and enjoy yourself. Healthy weight management involves not just thinking about yourself, but yourself as a member of a community, as a member of a family.

Pleasures, even though they may shorten your life a little bit, are what make life worth living. I hope people are willing to think of themselves and their diet in a more holistic way so that culinary culture doesn’t get instrumentalized into some kind of competition of who gets sick least and who weighs less.

Q: What advice do you have for someone who is genuinely interested in taking part in a dietary movement?

A: The first thing I would say is for anyone who ever thinks about going on a diet to realize that a diet is a medical intervention. Whatever the medical intervention is, whether it’s putting a brace on your knee or taking some kind of nonprescription painkiller, you always want to be careful because medical interventions have side effects. Diets have side effects. You could destroy your ability to enjoy food. This is a phenomenon I’ve seen in a lot of people; even I realized I wasn’t able to sit down and enjoy a meal because I would have this mental calculus to figure out what was good or bad for me. Doing this subconscious calculus takes away from your ability to enjoy life. Consult a dietitian or a gastroenterologist. Get yourself tested for celiac disease before you go gluten-free. Take it seriously, whatever diet it is, and seek the advice of a qualified professional. And also be humble.

Realize you might not be the ultimate authority on how your body works or whether or not a diet worked. “Be careful” is the advice I have. Try cooking for yourself if you have time, try sitting down for your meals instead of eating them on the run and try to appreciate your food and culinary culture. The solution to a lot of the health problems that are associated with what we eat is not a scientific one, it’s a cultural one. It’s trying to make time for eating and not think of it as a nuisance.

# # #

By Sam Roth (’17)

March 3, 2016