The case for equity in education

Education

Has higher education lost sight of a society in which diversity initiatives are not necessary?

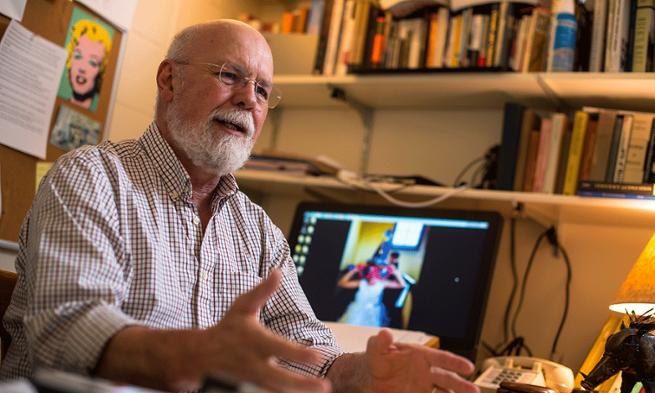

By Kenneth Wright, JMU professor in residence, George Wythe High School

For the past five years I have been a participant in JMU's Professors in Residence program, and I have had the opportunity to assist students at a couple of under-resourced Virginia high schools. First, I have helped these students come to understand that they can indeed go to college (not a belief they all hold); and, second, with meeting the administrative requirements of the going-to-college process (through completing college applications, financial aid forms, and appropriate scholarship documentation, among other things).

Professors in Residence is one element of JMU's efforts to increase diversity in higher education, and the program garners much good will for the university through presenting one of the many facets of JMU's extensive community service/civic engagement ethic.

Therefore, what follows should not be construed as a criticism of JMU's or of higher education's diversity efforts, but rather to suggest that we — we being higher education in general — have strayed from seeking the goal which engendered diversity initiatives in the first place: a society in which diversity initiatives are not necessary.

'Children's experiences outside of school along with their sociocultural situations have an effect on their abilities to learn.'

We strayed, I think, by absorbing our diversity efforts into our traditional institutional structures, which operate on the assumption that conditions necessitating their existence will persist. Unsurprising, for if we take a familiar traditional structure as our example, say a departmental or college curriculum committee, we can easily imagine a continuing need for a mechanism that vets proposals for new and/or modified curricula. However, when we place our efforts — necessary efforts to be sure — to increase diversity at our various institutions within those same structures, we can certainly be successful from year to year at helping to increase diversity in higher education, but at the same time we leave intact the social conditions necessitating those efforts.

Public schools are the sites through which current social conditions have the most significant impact on diversity in higher education, because, of course, the vast majority of each year's incoming college students are prepared, or not prepared, for college by our country's public schools. Many across our country seek to address preparedness issues by seeking equality in public education, and whereas equality in educational funding is a necessary goal, curricular equality through standardization, providing every child with the same education as if every child lives in the same cultural situation, leads to our relying on culturally dominant ethnic and economic discourses that ignore the lived reality of the children not raised within those dominant discourses.

Rather than seeking equality in education, then, our society should seek equity in education, defined as "existing in a society, when its institutions (especially schools) and individuals therein (school professionals, caregivers, and community members), provide students what they need to be successful academically, linguistically, culturally, socially and psychologically," according to the Social Justice Research Center.

Understanding the need for equity in education requires understanding that children's experiences outside of school along with their sociocultural situations have an effect on their abilities to learn. A seemingly minor inconvenience, such as a child needing to change schools midyear due to a change in residence arising from a family's economic hardship, means that the child must participate in the creation of a new teacher/student relationship and new social relationships in an environment wherein most of her fellow students have likely been with the teacher and one another since day one. How much more effect on a child's ability to learn, then, might long-term parental unemployment, deep poverty, even homelessness have on the child's preparation for learning?

'If our society does not consider our children's lived realities [parental unemployment, deep poverty, even homelessness] ...when designing their educations, then we — American society not schools or teachers — fail to prepare many of our children for success.'

If our society does not consider our children's lived realities, the cultural and ethnographic milieus of their school districts, when designing their educations, then we — American society not schools or teachers — fail to prepare many of our children for success.

In relation to higher education diversity initiatives, I would like to suggest that colleges and universities — recalling that the primary goal of diversity initiatives is a society with no need for them — embrace the concept of equity in education and add to their diversity efforts vigorous public support for it from all institutional levels.

JMU is a leading institution in promoting student success once students arrive at the university, we even have a center named for it; therefore, it seems a logical progression to expand our efforts to including fostering the success of students who, without equitable educations, might not enter college at all.

About the Author: Kenneth Wright is a professor in the JMU Department of Interdisciplinary Liberal Studies and the JMU Professor in Residence at George Wythe High School in Wythe County, Va. His article is adapted from his "Occupy Diversity" presentation delivered at the JMU Diversity Conference in May 2014.