The science of problems and solutions

Science and Technology

SUMMARY: Before beginning his second career as a professor, Walton spent more than 24 years at the Central Intelligence Agency in various roles. His years as a CIA analyst put him at the pulse point of history. Notably, during the 1992-1995 Bosnian War, intelligence developed by Walton and his colleagues was instrumental in the policy decisions made by the Clinton Administration during the armed conflict, the worst in Europe since World War II.

JMU’s approach to intelligence analysis produces career-ready graduates

By Jan Gillis ('07)

Could you manage too much of a good thing? Dr. Timothy Walton, professor of intelligence analysis at James Madison University, says that is exactly the challenge that today’s budding intelligence professionals will face in their careers: “The old problem was not enough data; today it’s too much and of an extremely mixed quality.”

CIA veteran

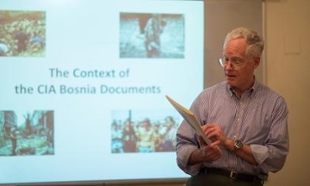

He would know. Before beginning his second career as a professor, Walton spent more than 24 years at the Central Intelligence Agency in various roles. His years as a CIA analyst put him at the pulse point of history. Notably, during the 1992-1995 Bosnian War, intelligence developed by Walton and his colleagues was instrumental in the policy decisions made by the Clinton Administration during the armed conflict—the worst in Europe since World War II. That work has garnered recent notoriety with the CIA’s release of almost 200 newly declassified documents on intelligence and presidential policy making; many were the handiwork of Walton and his colleagues. His responsibilities during the conflict gave him firsthand experience with the daunting burden of information overload. “During the Balkan crisis, we sometimes received 3,000 communications a day for analysis,” he says.

JMU’s scientific approach to intelligence analysis

His CIA career gave Walton unique insight on what makes graduates desirable to intelligence recruiters—knowledge that helps him build intelligence professionals who will be in demand. He is enthusiastic about the approach of Madison’s undergraduate program.

“JMU’s program is in the science faculty. At most other universities it’s connected with history, international relations, or political science,” he says. “We take the scientific method seriously. Systematic problem solving is our niche—teaching people how to better cope with problems.

“Getting up every morning and going after the bad guys—what could be better than that?”

The seasoned professional is realistic about the obstacles intelligence analysts face on a daily basis. “I’m reluctant to talk about problem solving,” Walton admits. “Most problems we work with—such as chemical weapons—you don’t get to solve. But you can cope with the problem, reduce it.”

At JMU, the development of critical thinking and reasoning skills is emphasized. “We teach students how to find the real problem, examine multiple explanations, and help to determine the best way to go,” he says.

There is an added bonus to this approach. Knowing how to apply analytics to problem management is a valuable skill equally prized in law enforcement and business arenas as well as national security intelligence. In short, there’s a wealth of opportunities for JMU graduates.

A grounded introduction

Walton introduces students to the intelligence business, teaching JMU’s core course on national security intelligence to sophomores. He is quick to dispel their illusions. “TV is not an accurate predictor of real life in intelligence analysis,” he says, “and this course provides a realistic view. It’s my favorite. I lived it; I know it; and people need to get beyond the James Bond fantasy.” Walton says that good analysts are primarily thinkers, comfortable with navigating bureaucracy, and adept at collaboration with professionals scattered across various governmental agencies.

“If yours is the issue of the day, your analysis can end up on the President’s desk in a daily brief. It will inform high-ranking officials including the Secretary of State and the Secretary of Defense,” he says. “During my time at the CIA, analysts were admonished to be the smartest person in the room—that’s a very high bar.” Walton proved his mettle many times as evidenced by his numerous awards and accolades. He considers the 1996 James R. Killian Award from the President’s Foreign Intelligence Advisory Board a special honor since board members advise the President on intelligence matters and give the award based on nominations from senior consumers. The Undersecretary of Defense for Policy nominated Walton for assisting the U.S. military peacekeepers who played a key role in ending the fighting in Bosnia.

Challenge and benefit

Today’s graduates will enter an intelligence field facing an unprecedented volume of information and high-risk scenarios. Nonetheless, Walton is confident that with the right educational grounding these future analysts can prosper. “Intelligence people no longer have a monopoly on the data,” he says, “but they have the strong ability to make sense, to make good judgments on the data.”

Walton offers a final, compelling recommendation for taking up the challenge of national security intelligence analysis. “Getting up every morning and going after the bad guys—what could be better than that?”

On March 19-20, 2014, JMU will host the conference “Intelligence and the Transition from War to Peace, A Multidisciplinary Assessment” examining the CIA documents on intelligence support to U.S. decision-making on Bosnia, 1992-1996. Learn more.