JMU Helps Discover New Breakthroughs in Lacritin Research

NewsBy Dan Armstrong, JMU Public Affairs

Ever since Madison Scholar checked in with Dr. Bob McKown about his research into the human tear protein lacritin more than three years ago, people have been calling to ask about the project. And for good reason, too.

The story was a sight for sore eyes for many of the 35 million sufferers of dry eye syndrome in the U.S. when McKown reported his team was manufacturing a protein that could help stimulate new tear production.

Now, not only is the four-institution research team nearing a partnership with big pharma, but also is continuing to discover new and potentially revolutionary uses for the little-known protein.

A Visionary Breakthrough

In 2001, University of Virginia cell biologist Gordon Laurie discovered the protein, which is secreted by salivary and lacrimal glands, and coined it lacritin. Early research suggested it had utility in stimulating new tear production and potential for large-scale manufacturing using recombinant DNA technology.

The next steps toward that goal required a well-organized biotechnology lab. Knowing the reputation of James Madison University's biotechnology concentration within the Integrated Science and Technology program, headed by McKown, Laurie introduced the idea of a research collaboration.

JMU, whose biotechnology program has since grown into an interdisciplinary major unto itself, would provide cloning of the lacritin gene and purification of the protein. More partners, including Eastern Virginia Medical School and EyeRx Research Inc. later would come onboard to guide clinical design and animal testing.

Currently, non-invasive pre-clinical testing is underway on rabbits and primates. Clinical testing on humans could be in the near future, according to EyeRx principal and EVMS professor Patricia Williams.

"We've proved that it works, and we've proved it's non-toxic," both of which are necessary components to gain FDA approval for investigational new drugs, Williams said. "What we've done is set up all the parameters. Now we're seeking corporate sponsors to develop this, and several companies have expressed interest. Once we have a partner, we think we'll have an excellent product that would be different from anything else on the market."

The collaboration, which brings together the expertise of groups from throughout the state, is the vital factor in the success of the project, McKown said.

"We can bring our skills together and create something none of us individually could do," McKown said. "When you bring together people with varying talents and similar interests, the sum can be greater than the parts."

JMU's Role

ISAT professor Ron Raab came onboard in 2003 to guide JMU's cloning efforts. In simple, researchers isolate and extract a gene for the protein lacritin and insert it into the cells of common bacteria, such as E. coli. The gene is then replicated when bacteria reproduce, and the cells make the protein.

The product then must be purified to remove the unwanted bacterial remnants and the thousands of other proteins that are created in the bacteria along the way, a process in continual refinement by McKown's team. The pure protein is then freeze dried and shipped to UVa. and EVMS as well as institutions around the globe for testing.

It's a complicated application of cutting-edge science, one requiring not only large funding, but also highly skilled personnel. For funding, the Lacritin Consortium has pulled in grants from the National Institutes of Health and other groups. But for manpower, McKown had to look no further than the students he teaches everyday.

"What's great about this is having three Virginia universities collaborate and work very closely together, engaging students-undergraduates, graduate students and post-doctoral fellows-to pursue science both for science's sake and to develop a product for the purpose of helping people," McKown said.

New Dimensions

While researching further components of the protein, Laurie and his team discovered the protein exhibited antimicrobial properties.

"Cornea cells, like any cells, must be regenerated often," McKown said. "What the Laurie Lab found was that lacritin stimulates not only tear secretion but also new cell growth."

Since then, McKown's research has shown that the protein, which is naturally secreted by the eye, is effective in fighting common eye bacteria such as Staphylococcus epidermidis, Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Staphylococcus aureus.

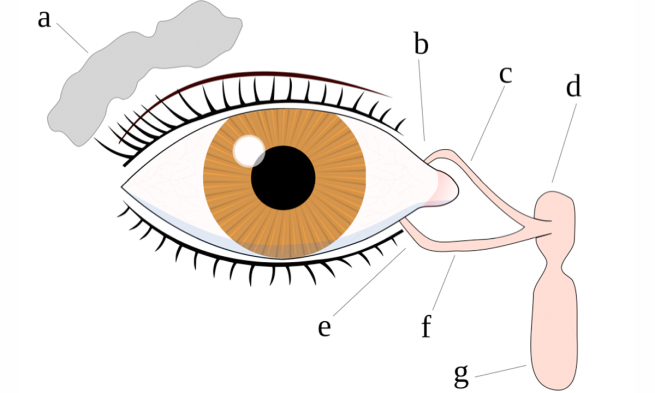

"Our defenses don't wipe out infection as much as they keep it from getting a foothold," McKown said. "The eye is bombarded with bacteria all the time. Those bacteria are flushed out, and the antimicrobial peptides help prevent infections."

In many people, though, including a large percentage of dry eye sufferers, lacritin is differentially downgraded, or appears in lower levels. Sufferers of dry eye also are often more susceptible to eye infection, McKown said, opening the door for recombinant lacritin's potential application as a topical remedy for both dry eye and eye infection.

Lacritin as a cell regenerator also could be beneficial in wound healing, including for patients recovering from eye surgery. That potential attracted yet another partner to the consortium, Walter Reed Army Medical Center.

The Army currently performs corrective eye surgery on more than 11,000 soldiers each year, said Lt. Col. Scot Bower, who heads the eye surgery program at Walter Reed. Wearing eyeglasses or contact lenses in the field pose numerous problems for soldiers, making eye surgery a more attractive option for the armed forces in the future.

"The more we learn, the more we realize we don't know. The body has evolved for so many millions of years, we have much more to learn," McKown said. "This protein turned out to be very challenging. This is a unique protein. But that's what makes it exciting-you learn things along the way."

Looking Over The Horizon

The consortium has created an impressive track record so far, including garnering more than a million dollars in grants, publishing numerous journal articles and receiving several patents. But McKown sees no end in sight.

"The science will never end. The more we learn about this protein, the more we find it does. There will be products that come out along the way, things will get finished, but then it moves on to other things," McKown said. "There can be benchmarks such as bringing a product to market. But personally, I just like doing the science. It's really fun. I would love it if the royalties from any products could pay for my research as long as I want."