Empathy in action

Independent Scholars

SUMMARY: Mariam Elassal (’24) champions change through youth justice and social advocacy.

From a young age, Mariam Elassal supported the underdog. She didn’t understand why inequality existed, but educated herself on its impact and became unrelenting in her empathy for others. “I care a lot about people, it bothers me that not everybody has the same opportunities.” That awareness led her first to social work because it influences change in individual lives and addresses inequality.

Before she came to JMU, Elassal did not fully understand her place in the world and how much impact she could make. She didn’t see herself as someone who could create wide-scale change. “But my parents were role models,” she says. “Growing up with strong community values due to my Egyptian background, I observed how a robust support network can positively impact lives. My parents emphasized the importance of education and empathy through their actions. They supported me no matter what, letting me make mistakes and learn from them even when my decisions didn’t align with who I wanted to be.”

Elassal is drawn to young people. When she was in the Social Work program at JMU, a professor mentioned the inauguration of a new Youth Justice minor. Elassal had already been thinking of working with dual-status youth— minors who encounter both the child welfare and juvenile justice systems. Taking the intro class, everything clicked, and she found Dr. Rita Poteyeva, an associate professor in the Department of Justice Studies, engaging. “She’s knowledgeable, personable, and warm. She instilled a lot of confidence in me, improved my writing, and developed my skills. We’ve stayed in contact since I completed the course — she’s been so supportive.” Poteyeva has designed a unique capstone class that involves students teaching and working with professionals to solve problems. “She guides students to discover things themselves, which I truly appreciate,” Elassal said.

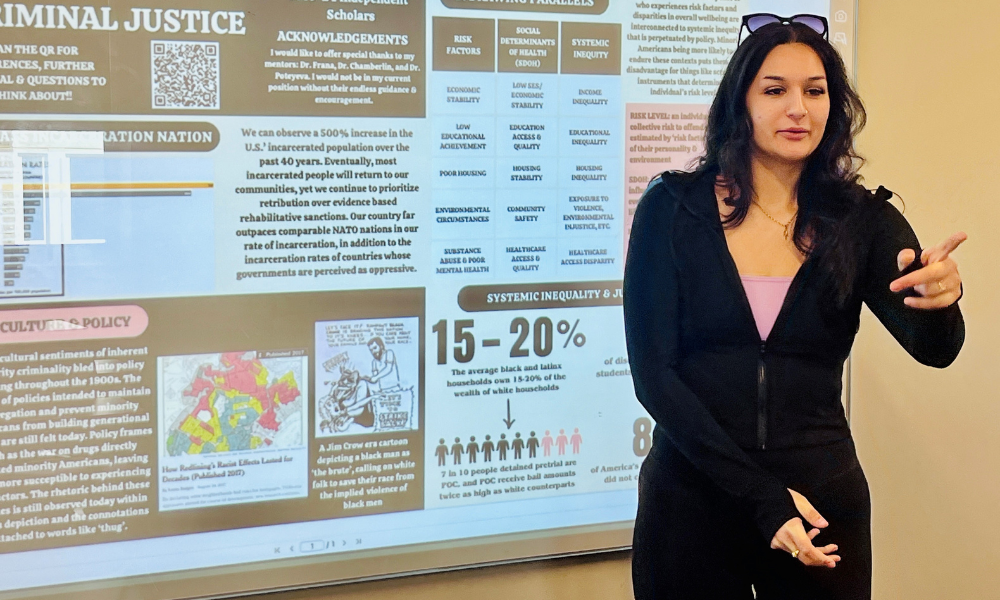

Elassal realized she couldn’t finish her youth justice minor if she continued in Social Work, and sought courses that focused on macro-level change. Her roommate mentioned Independent Scholars, and after learning about it, it seemed too good to be true. She contacted the program’s director, Matthew Chamberlin, explained her interdisciplinary interests in criminal and youth justice reform, and was admitted to the program. Equipped with this broader perspective, she now studies the challenges faced by individuals who have experienced incarceration.

When formerly incarcerated people face release and reentry to society, there are several factors which predict their likelihood to reoffend. “Individuals facing reentry have difficulty finding employment, limited access to education, and so much more. They often lack the support systems crucial to successful reintegration,” Elassal explained. She often discusses how these barriers to reentry stem from societal perceptions and stigmatization of those with offense records. “The logic of assuming offenders should have known better is why our criminal justice system is so punitively focused. It is why offenders face these barriers when they reenter society, and it’s why those barriers perpetuate our country’s devastatingly high recidivism rate. It hinders offenders’ ability to lead a normal life again.”

She states that all justice systems should prioritize rehabilitation over punishment, especially in youth justice jurisdictions. “Treating kids like kids is essential,” Elassal explained. “They are in a unique and malleable stage of learning, and adolescent brain science tells us that the punishments we tend to impose are generally ineffective. Methods that hold youth accountable without focusing on punishment, like restorative justice mediation, work well for youth offenders.” Justice systems have the unparalleled opportunity to make communities safer in the long run by listening to the research and rehabilitating youth offenders so that their behavior doesn’t continue into adulthood.

Elassal interned this past summer with the Fairfax County Juvenile and Domestic Relations District Court in Springfield, Virginia. “Fairfax County has put a lot of effort into implementing rehabilitative programs that we know work,” she said. “I was meeting kids who completed these programs and were very successful. They may have made horrible mistakes in the past but come out of these programs with outlooks that don’t align with offending behavior, and that’s the goal.”

Elassal’s internship with Fairfax County was supported by funding from the Innovation Center for Youth Justice at JMU, directed by Poteyeva. The Innovation Center for Youth Justice is the first initiative of its kind in the nation. The objective of the center is to improve prospects for youth offenders, enhance accountability, and strengthen community safety. The collaboration involves the JMU departments of Justice Studies and Social Work. John A. Tuell (’79), who serves as the executive director of the Robert F. Kennedy National Resource Center for Juvenile Justice, is also a partner in the venture. Tuell began his career in the Fairfax County Juvenile and Domestic Relations District Court.

J.J. Messier is an independent consultant for the RFK National Resource Center for Juvenile Justice and liaison between the RFK NRC and James Madison’s Innovation Center for Youth Justice. Messier witnessed Mariam’s work beyond the classroom during her internship in the Fairfax County Juvenile Court System. “Mariam is not only an exceptional student but also passionate about integrating research and data into reform work of social justice issues,” Messier explained. “I was able to see how she seamlessly wove her desire to affect policy change into the work of the youth justice system. Mariam will continue that passion as she works to prototype solutions to real-world challenges plaguing the juvenile justice system.”

Elassal hopes to influence national change by becoming a policy advisor or researcher for a youth justice organization. She serves as the student face of the Gandhi Center for Global Nonviolence and has already given presentations on her policy research at various conferences and meetings, including those organized by the Mid-Atlantic Regional Conference for Undergraduate Scholarship and the JMU Board of Visitors. “Mariam is one of the best student interns we’ve ever had at the Gandhi Center,” said Taimi Castle, professor of Justice Studies and director of the Gandhi Center. “Last semester, she assisted with the Beitzel Symposium on Artificial Intelligence in Higher Education and the inaugural Indigenous Peoples Day event. She is conscientious, dedicated, and responsible. I know she will make a difference in the world.”

The present moment is extraordinary, Elassal explained, with the internet providing a firsthand look at global issues. Seeing videos of social justice movements, for instance, is different from just reading about them. This accessibility allows more people to recognize the scale of these problems. In recent years, heightened awareness and discussions online have shed light on systemic issues. This awareness fosters greater understanding of social inequities. “It’s fascinating to witness activism and advocacy on social media in real-time,” she said. Social movements in the past relied on word of mouth, making it harder for people to access different perspectives. Now, with social media, it’s easier to find varying opinions.

People engage in social media activism, but sometimes feel absolved from the responsibility to advocate in other ways. “For me, activism means non-violent demonstrations and civil disobedience,” Elassal said. “Peaceful resistance has been a catalyst for change throughout history, as in the civil rights movement. It disturbs the status quo, prompting reflection and change. Today, any form of disobedience is often perceived as violence, but genuine activism challenges norms without resorting to violence.”

Solving criminal and youth justice issues requires addressing how people think about and treat each other. Notes Elassal, “We are all better than our worst mistakes. Everybody is inherently deserving of empathy and dignity for the simple fact of being human.” In this context, Elassal advocates for justice reform by employing her education in conversation to challenge narratives regarding how we should handle crime and the opportunities available to offenders. “I think even when I talk in our Independent Scholars classes, I subtly change people’s perspectives on the need for systemic change.”

“Many beliefs persist simply because they’ve always been that way,” Elassal explained. “When you force people to confront why they believe the things they do about those with offending records, they usually don’t have an answer. They think these things because these ideas align with the current societal context, and they haven’t considered that we can create a new context. Even when I’m having these conversations, I’m not necessarily changing people’s minds. They’re being introduced to information, taking that information in, and working with it. They’re changing their own minds. Patience can be difficult in these conversations, but getting others to listen to ideas or contexts they haven’t thought about requires your own understanding of their beliefs. It’s the only way.”