Saluting an uncommon colonel

JMU News

SUMMARY: The late Col. Frances Weir (’49) was a career Women’s Army Corps officer. She served with distinction in Europe and Vietnam, at the Department of Defense, and on various U.S. posts, specializing in transportation and logistics. In 1976, she became the first woman to lead a mostly male Army brigade. Upon her death in September, JMU received its largest cash gift to date: $6 million for student scholarships.

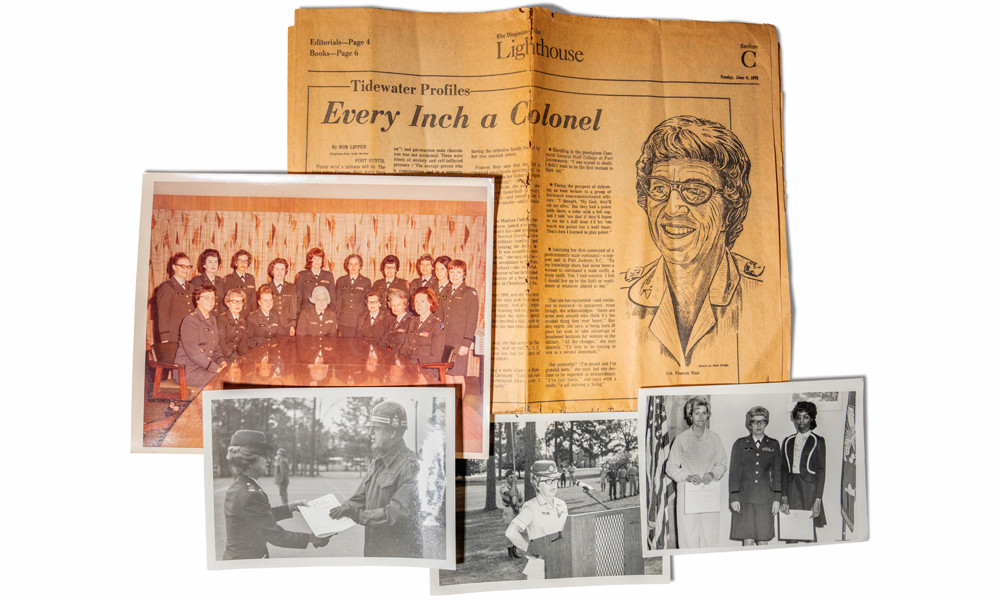

In early December, a box of the late Col. Frances Weir’s (’49) effects arrived at JMU. After being meticulously unpacked, it was difficult to decide which items were most remarkable. Was it the photographs of the 5-foot-2-inch officer in army-green fatigues and combat boots in Saigon, Vietnam? The half-dozen bronze and gold military-service medals? The newspaper clippings charting her rise from second lieutenant to colonel? Or was it the decade’s worth of potent leadership descriptions in her service evaluations?

The box of possessions arrived ahead of another gift Weir had entrusted to her alma mater: the university’s largest cash gift and largest gift solely for scholarships. At more than $6 million, the Frances Weir (’49) Endowed Scholarship will enable the Office of Financial Aid and Scholarships to award approximately $240,000 annually in scholarship funds in perpetuity. Her endowment will support students who demonstrate financial need and who maintain a GPA of 3.0 or higher with scholarships that are renewable for three years.

“Col. Weir was an impressive military leader and pioneer,” said President Jonathan R. Alger. “She broke new ground throughout her career, and she has done so again with her gift to JMU. Scholarships are a top priority for the university, and Col. Weir’s gift will open doors to the Madison Experience for many promising and deserving students, whose lives will be better for it.”

Ceal Gorham, Weir’s friend and neighbor of nearly 30 years and the executor of her will, described her as “a very caring and generous person — but she didn’t like to let you know it.”

After graduating from Madison College in 1949, Weir enlisted in the Women’s Army Corps, the women’s branch of the U.S. Army. Through the WAC, Weir served in Europe and Vietnam, at the Department of Defense, and on various U.S. posts, specializing in transportation and logistics. In 1976, she was “the first WAC to lead a mostly male brigade,” per the Pentagram newspaper. “She marched along a line of military that was very unusual,” Gorham said. “And we found out more after she died than we knew when she was alive.”

|

| (L-R): Weir’s service medals include the Legion of Merit with Oak Leaf Cluster, the Bronze Star, the Meritorious Service Medal, the Joint Service Commendation Medal, the Army of Occupation Medal and the National Defense Service Medal. |

Taking the heat

Weir retired to San Antonio, Texas, in 1978, introducing herself to new friends and neighbors as Tina, a spinoff of her lifelong epithet, “Teeny.” After nearly three decades of active service, she spent retirement gardening, golfing and playing poker, which she had learned from a group of noncommissioned officers. Weir told The Virginian-Pilot in 1973 that when faced with the prospect of delivering an hourlong lecture to them, “I thought, ‘My God, they’ll eat me alive.’ But they had a poker table there, a table with a felt top, and I told ’em if they’d listen to me for a half hour, I’d let ’em teach me poker for a half hour. That’s how I learned to play poker.”

In 1994, she designed and built a house in a new neighborhood in San Antonio, where she met Gorham. That first year, “I saw more of her backside than her front side, because she was always bent over working in the yard,” Gorham said. The decision to retire to Texas was one Weir “always lamented,” Gorham said. “She’d say, ‘You can’t grow anything here. It’s too hot!’”

In the neighborhood, Weir had distinct friendships. There was Mary, with whom she shared a love of cats and a glass of wine in the evenings. There was Louise for lunch and shopping. And there was Gorham, a retired nurse, to attend her medical appointments — and ultimately oversee her estate.

A skilled negotiator and a second-rate cook, Weir organized a way to share good food with good company — no cooking skills required. Outside of a steak, “she couldn’t cook to save her soul,” Gorham said, “but she loved to go grocery shopping.” She made a deal with her neighbors: She’d buy the food, if they would cook it. “We probably had dinner together in the latter years of her life at least once, if not twice, a week,” Gorham said.

For Louise’s 80th birthday, Weir organized a parade through the neighborhood to celebrate. An active gymgoer who does Pilates, Louise “does not need a wheelchair by any stretch of the imagination,” Gorham said, “but Tina orchestrated this thing where we decorated a wheelchair, put her in it and pushed her down the street.” Weir gave everyone a role. Louise’s daughter pushed the wheelchair, Gorham texted neighbors to come outside for the parade, and Weir led the procession behind the wheel of her car, where she delivered round after round of honks.

‘Ability, spirit and spunk’

“The idea of joining the Army intrigued her,” wrote Ben Lipper of The Virginian-Pilot. From her sister Dorothy’s perspective, “she had two choices. She could become a school teacher or she could go in the service, and she decided that the better of the two things was going in the service.” Weir was accepted to Officer Candidate School at Fort Lee, Virginia (now Fort Gregg-Adams), then the location of the Women’s Army Corps Training Center. After eight weeks in basic training and six months in OCS, she emerged as 2nd Lt. Weir.

As a new WAC officer, Weir would have received “The Package” — a short workshop on how to do makeup, style hair and wear the feminine WAC uniform properly, according to Amelia Underwood (’13M), an expert on women in the military who teaches in JMU’s Department of Learning, Technology and Leadership Education. “It was a very big concern about women maintaining their feminine appearance,” Underwood said, “even though they’re in this masculine field.”

Weir’s early career is largely unknown, a common problem among Army women. “An understanding of how women have contributed in the military is just a missing component in our historical record,” Underwood said. Today, the U.S. Army Women’s Museum at Fort Gregg-Adams is the largest repository of archival materials for women in the military, but most records still need to be processed for researchers.

“There is a reason Army women’s history is hard to find,” said Alexandra Kolleda (’13, ’20M), a public historian and education specialist at the museum. “It’s because in the Army, [women] are the minority and perhaps the ones who are not seen as significant. But all that’s changing, which is why this is important work.”

With Kolleda’s help, a smattering of records placed 31-year-old Weir at the WAC School, a cluster of 22 cream-colored buildings nestled amid pines, oaks and sweet gum trees in Fort McClellan, Alabama, in 1958. After World War II, more than 200 military occupational specialties were open to women, but “they were supposed to be more administrative, logistics-focused tasks,” Kolleda said. After promotion to captain, and then major, Weir attended the prestigious Command and General Staff College in Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, a 20-week associate course open to only four WAC officers per year. “I was scared to death,” Weir told The Virginian-Pilot. “I didn’t want to be the first woman to flunk out.”

In 1966, Weir was promoted to lieutenant, and her assignments at The Pentagon began to reflect a growing awareness of her abilities. “She should be considered for the most responsible assignments available to a WAC officer,” wrote Lt. Robert Cushing. “Her greatest strength lies in her ability to work quickly and coolly under extreme pressure while maintaining a warm and friendly manner.”

By the end of 1968, she was coordinating all programming activity within the Office of the Assistant Chief of Staff for Force Development, and her superiors took notice of her “ability, spirit and spunk equaling the highest standards of the officer corps and the general staff.” She was personally recommended for an important assignment in a combat zone: the Republic of Vietnam.

|

Rising to the challenge

In January 1969, 41-year-old Weir arrived in Saigon to oversee personnel in the U.S. Army Support Command. “A large majority of women assigned to Vietnam who weren’t nurses were assigned to the Women’s Army Corps detachment,” Kolleda said. Only a handful of women served in the Vietnam combat theater. Weir was one of them.

From the beginning of her military career, she was often one of the few women — or the only — in an all-male unit. “Her colonel was more worried about where this little woman was going to use the restroom than he was about her surviving,” Gorham recalled. “But she did not sit on ceremony, she was not fussy at all.”

As commander of personnel in Vietnam, Col. John Murray described Weir as “the calm storm center of personnel actions” and the “seer staying ahead of the relentless daily rotations of strength and skills.” She was promoted to the assistant chief of staffs for personnel, commanding pivotal supply and transportation logistics to ensure soldiers had what they needed at all times. She had an unmatched logistical prowess, or as Murray described it, “the versatility of a genie.”

And yet, Weir had arrived in Saigon without combat training, because Army women weren’t given any. Trained separately from the rest of the Army, when WACs were dropped into war zones, they were issued no weapons and were ill-equipped to defend themselves. “It was fraught with danger,” Underwood said, “and women just rose to the challenge no matter what.”

While Weir was in Vietnam, Dorothy knew about the white cat her sister had found in a bunker and named Charlie and about the care packages of food their mother sent through a U.S. merchant marine. “She would have just starved to death, if it hadn’t been for a friend of ours that was on a ship outside of Vietnam,” Dorothy said. “My mother would tell him where my sister was, and he’d leave the ship and take her the food.” The packages included Weir’s sole culinary specialty: steak. “They would grill these steaks out and, needless to say, she was quite popular,” Gorham said.

But there was much about Vietnam that Weir chose not to disclose to family and friends. “She said Vietnam was the worst place she ever was in her life,” Dorothy recalled. “I believe it was so bad that it was better to keep it hidden inside of her, instead of discussing it openly … It was a part of her life she wanted to forget.”

From doubt to admiration

Not everyone believed that an Army woman could hold her own in a combat zone. Brig. Gen. Arthur Hurow was candid about this in her service evaluation. “I frankly had some doubt that any WAC officer, however outstanding, would have the background and capability to control the manpower and G-1 dynamics of the largest Support Command in this combat theater,” he wrote. “This adverse inclination quickly changed to outright admiration. In place of doubt of capability, I have monumental conviction of it.”

|

“Wears the smallest boots in the headquarters but has the biggest kick. A potent professional. Joan of Arc must be in her lineage.” — Retired Maj. Gen. John E. Murray |

Other superiors didn’t require the same amount of winning over. After comparing Weir to Joan of Arc, Murray added, “She moves from sublime concern with the individual to quick-witted exposure of the ridiculous. Straight is the word for her. Straight forward, keen as a straight razor and possessor of all the confidence of a poker player holding a straight flush. When the WAC gets its first star, she should wear it.”

Despite accolades in her evaluations, promotion to brigadier general did not hinge on Weir’s performance alone. “Up until 1967, there could only be two female colonels in the entire Army,” Kolleda said, “and [the two] were the director of the Women’s Army Corps and the director of the Army Nurses Corps.” In 1970, three years after President Lyndon B. Johnson signed legislation to remove promotion restrictions for Army women, both colonels were promoted to brigadier general. Brig. Gen. Elizabeth P. Hoisington joined the WAC during World War II, “so she had longer service,” Kolleda explained, “but otherwise, she had a lot of the same skills and qualifications as Weir.”

|

“Her performance, in comparison with other officers, principally male, was outstanding. … Professionally, she is faultless.” — Lt. Robert Cushing |

By the end of Weir’s deployment to Vietnam, her evaluations contained a statement that had once seemed impossible to say of an Army woman: “She is fully capable of performing her duties in a combat zone.” In 1969, “saying that she can compete alongside of men …” Underwood mused, “that’s something that they wouldn’t really say.” For her exemplary service in Vietnam, Weir was awarded the Legion of Merit and the Bronze Star.

‘An awful lot of eyes’

In 1970, Weir returned to The Pentagon, where she adeptly handled assignments that ranged “from the bizarre to the most complex with utmost equanimity,” wrote D.H. Havermann. As a program analyst for the Office of the Secretary of Defense, she had to attend many social events and maintain the expected polish of a WAC. “She couldn’t go to the beauty parlor every day,” said Gorham, “but she had a wig or two that she could wear and just put on so that her hair always looked presentable.”

With each passing year, calls for promotion in Weir’s evaluations became more emphatic. In 1970: “Lt. Col. Weir should be promoted to the highest level of her branch.” In 1971: “Lt. Col. Weir is general officer material.” Finally, in 1972: “Colonel Weir should be groomed to become the director of the WAC.” But the Army still kept superior officers like Weir from rising in rank.

Instead, Col. Weir was carefully selected by the chief of staff to be president of the Army’s Conscientious Objector Board, which reviewed the cases of those who opposed the Vietnam draft on moral or religious grounds. The issues the board faced required “wisdom, sensitivity and administrative ability … characteristics Colonel Weir displayed to an uncommon degree,” wrote Col. William Louisell Jr., who retired as brigadier general. Then, Weir was off to the Sixth Army headquarters at the Presidio of San Francisco, California, where she advised the WAC director on all aspects of WAC personnel for one of the largest theater commands.

By 1973, the Army was changing, and 46-year-old Weir was making history in South Carolina. The Equal Rights Amendment was in Congress, the military draft had ended, and the Army was transitioning to an all-volunteer force for the first time in history. To offset the exponential drop in numbers, the Army began to focus on recruiting more women, which necessitated more opportunities for their promotion. That fall, the Pentagram wrote an article naming Weir “the first WAC ever to head a major unit at Fort Jackson.” As commander of Headquarters Support Command, she oversaw “any kind of task that kept Fort Jackson up and running,” Kolleda said.

So novel was the concept of women commanding men that mention of Weir’s assignment in Fort Jackson made its way into the 1974 TIME magazine article, “The Sexes: Skirts and Stripes.” But the world was late, and Weir had already spent two decades among — and leading — men. She seemed to have grown tired of the conversation and the assumed differences in experiences from that of her male counterparts. Before her historic assignment, when the Pentagram asked how her experience of being a female in an all-male unit would affect her at Fort Jackson, Weir said, “My feelings are not all that different from those of a man who goes into a new job. There is always the feeling that you don’t know enough about your new assignment. The one difference I can sense is there are going to be an awful lot of eyes on what I’m doing. The fact that I’m wearing a skirt surrounded by people wearing trousers makes me stand out.”

‘Exceptionally outstanding’

In 1976, 48-year-old Weir made her final military move, this time back to Virginia, where she inhabited an unlikely role as secretary in the U.S. Army Transportation School. But Weir rapidly outgrew the position and was quickly appointed deputy assistant commandant of the school. “She operates at full capacity all the time,” wrote Brig. Gen. Arthur Junot. “She has been appointed deputy assistant commandant because of her full grasp of school operations, her exceptional competence in organizing and supervising a large staff, and her amazing grasp of technical transportation doctrine.” At the time, Weir was one of about a dozen female colonels in the Army, not including nurses.

As deputy assistant commandant, Weir advised on training programs for various military occupational specialties, ensuring soldiers were properly trained so the entire Army had the necessary method of transportation, supplies and personnel across the continental U.S. and overseas. A battle with Graves’ disease pushed her toward an early retirement. “If not for the condition, she likely would have stayed on,” Gorham said. Weir’s final service evaluations brimmed with calls for promotion, with some superiors going so far as to underline the phrases “exceptionally Outstanding” and “Star Rank.” But when she retired in 1977, just one year before the WAC was dissolved and women were integrated into the Army, she was forever a colonel.

|

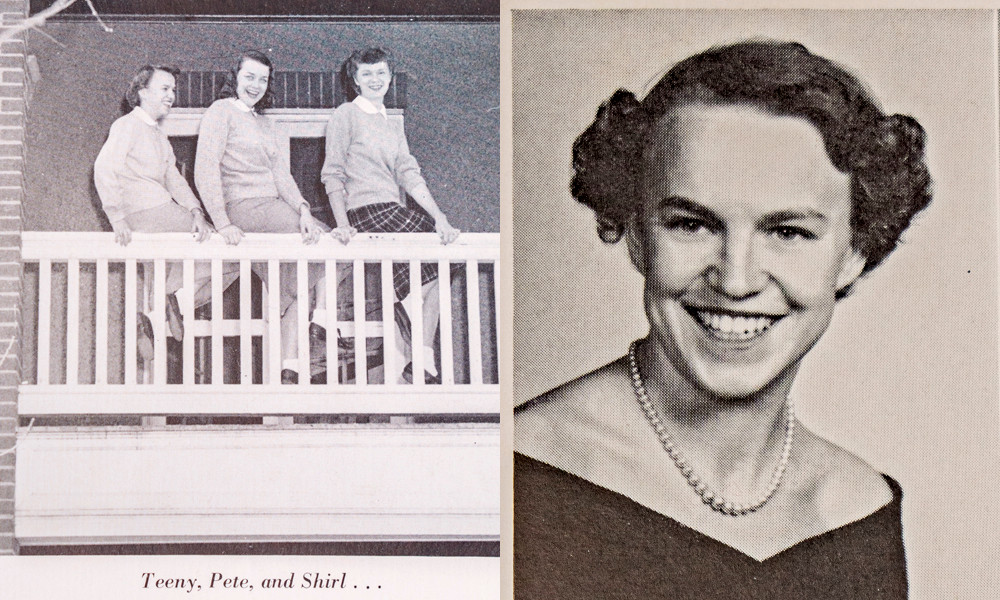

| Weir during her Madison College days: (L-R) sitting on the ballustrade of a residence hall with her sorority sisters; senior portrait in the 1949 Schoolma'am |

‘Bound and determined’

“Teeny was the type of person that could be over an army,” Dorothy said. The eldest of three daughters, Weir was born in 1927 in Winchester, Virginia. “I don’t remember [her] ever being called anything but Teeny,” her sister said. “I didn’t know what her first name was for years.” Their father managed a farm, and Weir said she enjoyed a “typical, small-town upbringing,” per The Virginian-Pilot.

“She always knew she wanted to succeed,” Dorothy said, “and she just didn’t want to be just a housewife.” Weir talked about her desire to attend Madison College, and growing up during the Great Depression, she knew she would have to work to pay her way. But “she was bound and determined to get a college education,” Dorothy said.

Weir’s childhood nickname followed her to Harrisonburg. At Madison, Teeny majored in business, routinely made the dean's list and joined Pi Omega Pi, Pi Kappa Sigma and Business Club. She spent her summers working as a secretary for a beer company to afford tuition, an experience that would shape the core of her philanthropy. “She was never boy-crazy,” Dorothy said. “She was more excited about education.” Weir’s decision to attend Madison College inspired other family members to become Dukes, including her nephew, John Anderson (’70), and great-nephew, Jake Anderson (’23). “We continued the tradition,” John said.

Despite meager earnings in the military, Weir had made a series of wise investments in retirement, and regularly supported charities for children and cats. “But education was always very much her focus,” Gorham said. Before her death, Weir was a Women for Madison Amethyst Circle founder and donated $240,000 to JMU to establish her scholarship endowment. Gorham suspected that Weir felt a sense of indebtedness to her alma mater. “It got her out of Winchester, Virginia, into a life that she never would have had but for the ability to get an education and go into the military as an officer.”

“She always wanted to help somebody else,” Dorothy explained, “so that they wouldn’t have to work as hard as she did.”

Moved by her unrivaled generosity and leadership, President Alger chose Weir to receive the 2024 Presidential Award posthumously at the annual JMU Alumni Association Alumni Awards in April. The award honors an individual or group who leads in ways that are especially relevant for our time.

|

“Col. Weir was an impressive military leader and pioneer. She broke new ground throughout her career, and she has done so again with her gift to JMU. Scholarships are a top priority for the university, and Col. Weir’s gift will open doors to the Madison Experience for many promising and deserving students, whose lives will be better for it.” — President Jonathan R. Alger |

At the end of her career, Weir told The Virginian-Pilot, “I don’t think I was a dedicated career woman. It just turned out that way.” How did the colonel describe her military career? “I’ve just been a gal earning a living.”

Others describe her — and her impact — differently. “She really was one of a kind,” Gorham said. “She was a good woman,” Dorothy said. “She had a great heart.” At her retirement from the Army, Col. Harold Small, who retired as major general, wrote: “Her retirement will weaken the ranks of the Officer Corps.” Maj. Gen. Alton Post, who was later inducted into the Transportation Corps Hall of Fame, wrote more simply, but no less true, “Col. Weir was very good for the Army.”