Faculty Research Aims to Cure Frog Disease

News

Skin fungus isn’t life-threatening, unless you’re an amphibian.

Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis (Bd) is a harmful skin fungus that affects a host of amphibious species, such as frogs and salamanders. In many cases Bd is life-threatening, or even deadly, because it disrupts the breathing functions that take place on the skin of an amphibian.There is no known cure for Bd, but JMU biology professor Reid Harris is working to try and change that through the use of protective bacteria.

It was during the late 1990s when Harris went to listen to a speaker talk about how mother salamanders could pass probiotics — or protective bacteria — to their eggs. At the time, Harris was also working with salamanders, a species that had been heavily affected by Bd, when he put two and two together.

“At some point it clicked that antifungal bacteria can protect against fungus, we have a fungus that attacks the adults, it just all clicked,” Harris said.

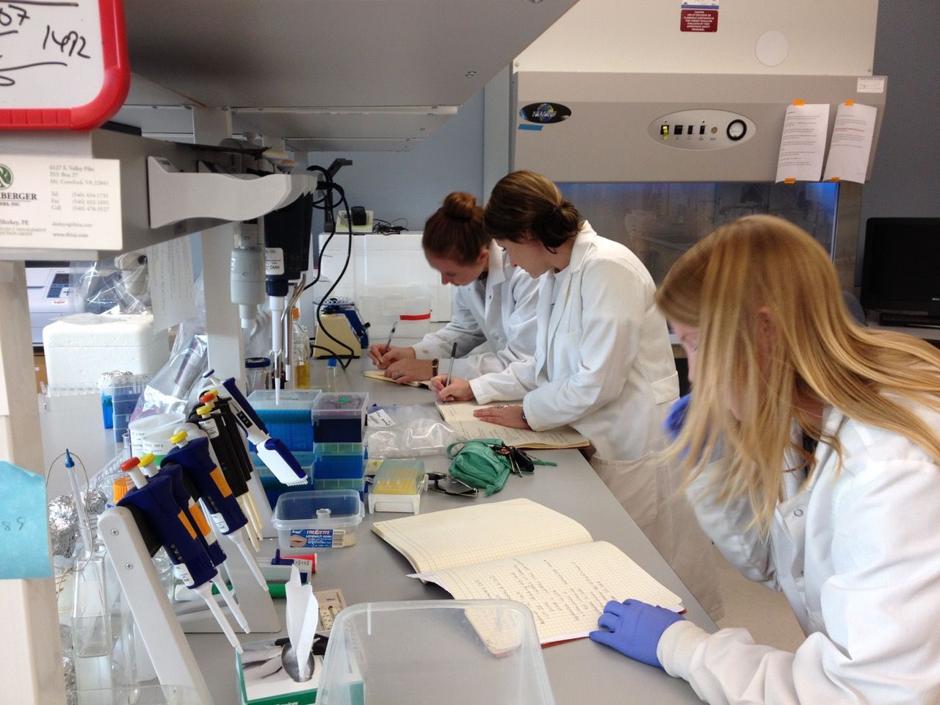

Now Harris and his team of biologists are trying to find the correct formula for a probiotic that could be applied to an amphibian’s skin to protect them from the harmful fungus that has decimated amphibious populations.

“If we can get a working probiotic, we can potentially save entire populations,” Emma Bales, a senior biology major and member of Harris’ team, said.

According to Bales, saving these populations are mutually beneficial to humans as many amphibian populations help control insects, like mosquitoes, which can carry diseases like malaria..

According to Harris, Bd has been found on six of the world’s seven continents, the exception being Antarctica, where no amphibians live. While the origin of Bd hasn’t been proven, the effects are indisputable as it has destroyed scores of amphibians across the world.

Although the fungus didn’t reach North America until the mid-2000s, it hasn’t taken long to make its mark, and it’s already responsible for a 40 percent decline in the amphibian population in the Panamanian mountains.

There are two main reasons for the quick spread of Bd: a lack of immunity in native amphibians and the pathogen being airborne. This mean that when a non-native amphibian carrying both Bd and an immunity comes into contact or even gets near a native amphibian, the disease will be passed on since no resistance exists.

So far there have been two major successes of the probiotic — a lab trial in 2009 and a field study that took place between 2010-11. In both cases the team used frogs with Bd, treating some with a probiotic while leaving others untreated. In the lab trial, all that were treated survived, while those that went untreated died. In the field test, which used mountain yellow-legged frogs, 39 percent of the treated frogs were recovered after a year in the wild while none of the untreated frogs were recovered.

There have been successful moments, but the probiotic is still in need of perfection and a variety of different strands of protective bacteria are currently being tested. This testing involves infected frogs being shipped to JMU where they are given a bath in the probiotic dissolved in water.

JMU and its collaborators are trying to establish how long the probiotic can remain on the test frogs. According to Eria Rebollar, a postdoctoral working on Harris’ team, the next step would be trying to get the probiotic to work in amphibians’ natural environment.

“It would be really, really important if we could come up with a strategy to help amphibians to survive against this disease,” Rebollar said. “It’s very hard to apply probiotics in the wild, but we think it’s one of the strategies that we could apply.”

In addition to their success with amphibians, Harris’ team has also been able to apply their probiotic research to humans by theorizing that an anti-fungal bacterial could control athlete’s foot. The project would see a type of bacterium that already exists on humans manipulated in a way to produce anti-fungal metabolites that would be preventive.

“We were able to show that a bacteria that occurs on humans, was able to … inhibit the athlete’s foot fungus [in a petri dish]. So we were also able to get a patent on that through JMU, and that’s pretty much as far as we’ve gone,” Harris said.

Other labs and companies have shown interest in continuing the project, which, according to Harris, is part of an important group of treatments that offer alternatives to antibiotics.

“There’s always a place for antibiotics, but they need to be used more selectively,” Harris said. “The idea is to use good bacteria to kill bad bacteria, instead of antibiotics, which just kill everything.”