Not forgotten

Raleigh Marshall ('05) discovers his great-great-great-grandfather, Paul Jennings

Community Engagement

SUMMARY: JMU alumnus Raleigh Marshall ('05) is a descendant of Paul Jennings, an African American enslaved attendant to James Madison and his family.

Editor's Note: This story was created, in its entirety, before the George Floyd murder and subsequent protests around America and the world.

By Jazmine Otey (’20)

Raleigh Marshall (’05) recalls being surrounded by history since elementary school. Coach lamps that once belonged to Founding Father James Madison were mounted on the wall in Marshall’s basement.

There were also nearly a thousand black-and-white photos scattered about, many of which were taken by Addison N. Scurlock, a prominent photographer in Washington, D.C.’s African American community. Within the collection was a photo of Marshall’s great-grandmother, Pauline Jennings Marshall.

But it wasn’t until 2008 that Marshall discovered the significance of the family heirlooms within his ancestral home. Through his great-grandmother, he is the great-great-great-grandson of Paul Jennings, an African American enslaved attendant to James Madison and his family.

|

"There is a weird feeling that grips you when you are in contact with something that you know for certain one of your ancestors from way back was in contact with." — Raleigh Marshall ('05) |

Elizabeth Dowling Taylor, a researcher, author and former director of education at Montpelier, Madison’s estate, invited Marshall to Montpelier to participate in a reading of the preamble of the U.S. Constitution, along with collateral Madison descendant Madison Iler Wing.

Marshall realized the magnitude of Taylor’s research and his heritage when he saw the large crowd assembled for the reading in front of the restored plantation mansion.

“I was shocked at how many people were there [for the reading], and how many people considered this plantation legacy to be important enough to them to cut out of work and organize all these field trips for [local school] kids,” Marshall said.

At first, Marshall was indifferent about the newfound knowledge concerning his ancestry because he knew that many slaves worked for Madison. While attending JMU, Marshall was unaware of his unique tie to the university’s eponym. He’d chosen the university for its attractive campus, amiable student body and exceptional computer science program. Marshall recalls pleasant memories from his time at JMU and was an engaged, active student. He served as vice president of the Tae kwon do Club for two years and as president his senior year. He was also a member of Zeta Beta Tau and an SGA representative.

With the help of Taylor, Marshall learned more about his family heritage and became much more fascinated about his family history.

|

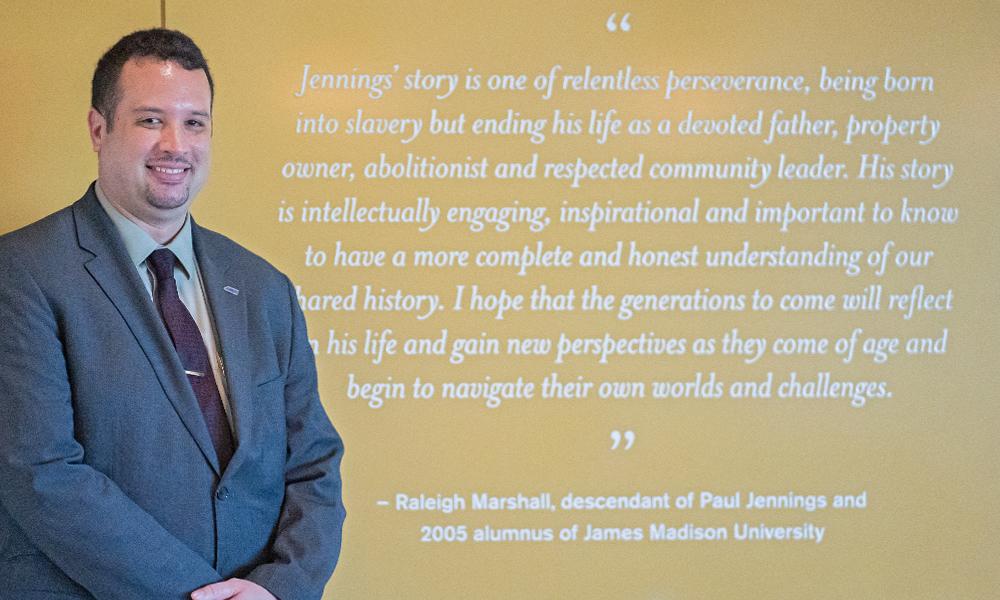

| Raleigh Marshall speaking at the opening of Paul Jennings Hall in October 2019. |

Since a young age, Taylor has had a keen interest in race relations and even attended a Martin Luther King Jr. rally as a child. While she was director of education at Montpelier, she decided to research Jennings. She was motivated by the limited amount of research and findings on him and the fact that his memoir, A Colored Man’s Reminiscences of James Madison, hadn’t been reissued since it was published in 1865.

After several years of research, Taylor found herself captivated by Jennings’ story. What originally was supposed to be a biographical essay, combined with Jennings’ memoir, developed into a book-length biographical narrative, A Slave in the White House: Paul Jennings and the Madisons.

Marshall’s first face-to-face interaction with Taylor was at the Montpelier event. Taylor presented him with a Constitution-sized piece of paper that bore his family tree with a copy of Jennings’ signature at the bottom.

“Beth Taylor kind of found me first,” Marshall said. “She found out that I was a Jennings descendant, and then found out that I had a lot of physical artifacts in the house that were worth examining. She was able to actually dig into all the records [and] connect all the dots. If you need to know any information about Paul Jennings, she’s probably the most knowledgeable person to talk to, even including most of his actual descendants.”

Taylor’s research motivated her to portray Jennings as more than just Madison’s slave and instead speak on how he triumphed despite living in a time of great tribulation.

“Yes, of course, he has an important connection with James Madison, and he was an eyewitness to important history,” Taylor said. But she wanted to ensure that she accurately “honored and recognized him for the remarkable person [he is] and his compelling story.”

|

| Descendants of Paul Jennings gather at Montpelier for a family reunion. Raleigh Marshall is in the back row on the left. |

Jennings is recognized for a plethora of achievements.

During the War of 1812, as British troops prepared to set fire to the White House, Jennings helped save a portrait of George Washington by Gilbert Stuart.

In 1846, he moved to purchase his freedom. Dolley Madison sold Jennings to an insurance agent named Pollard Webb for $200. Statesman Daniel Webster bought Jennings from Webb for $120. Webster immediately freed Jennings. He had essentially loaned Jennings the money to purchase himself, and Jennings paid it off at the rate of $8 a month working as Webster’s dining room servant.

Two years later, Jennings, white abolitionists and other free African Americans, planned the Pearl incident, one of the largest recorded, nonviolent slave escape attempts in history. A group planned to board the Pearl and sail south on the Potomac River, then north up the Chesapeake Bay and Delaware River to freedom in the North. However, the mission failed due to the contrary tides, and a posse caught up with the vessel. Many of the slaves were then sold to plantations farther south as punishment.

In 1853, after working hard to ensure his family was well-established in Washington, D.C.’s free black community, Jennings purchased property on L Street.

In 1865, Jennings wrote the first White House memoir, which illustrated the relationship between a slave and slaveholder and also provided his perspective of the Madisons.

|

| Jennings' descendants at the White House in 2009. |

Taylor was a catalyst in arranging for Marshall’s family heirlooms to be curated by professionals at the African American Museum of History and Culture. She also helped organize a Jennings family reunion at Montpelier, which drew several generations of descendants from throughout the U.S.

She arranged a private tour at the White House on Aug. 24, 2009—the 195th anniversary of the date Jennings helped rescue the portrait of Washington. That day, Jennings’ descendants gathered around the portrait for a family photo.

“There is a weird feeling that grips you when you are in contact with something that you know for certain one of your ancestors from way back was in contact with,” Marshall said.

The moment had an added layer of depth because another black man, Barack Obama, was president at the time.

“The fact that Paul Jennings had the only allowable role for a black man in the White House in his day, as a liveried footman, and now the first African American president and his family were making their home in that same distorted structure, made it all the more exciting,” Taylor said.

With his heightened appreciation for his heritage, Marshall is now a member of the Pearl Coalition. The group’s mission is to build a replica of the 1848 Pearl ship with the help of youth and volunteers as a means of educating them on “the array of racial, social and economic factors, [and the] contributions of the people and places involved in the Pearl escape.”

|

| Raleigh and Aria Marshall at the dedication of Paul Jennings Hall in October 2019. |

Marshall, an engineer at Microsoft, is also a father to a 1-year-old girl, Aria Marshall. He hopes to instill their family’s legacy in her as she grows up.

“It’s actually a deliberate plan that I have to do a bit of a better job of it than my dad did for me,” Marshall said. “I don’t want to overwhelm her with it because it’s a lot. But I will, over time, strategically drop nuggets of information on her to see how much of an interest she has independently.”

“You know, there’s an old saying that the worst thing is to be forgotten,” Marshall said. He refuses to let that happen with his family’s legacy.

###